Infant Screening

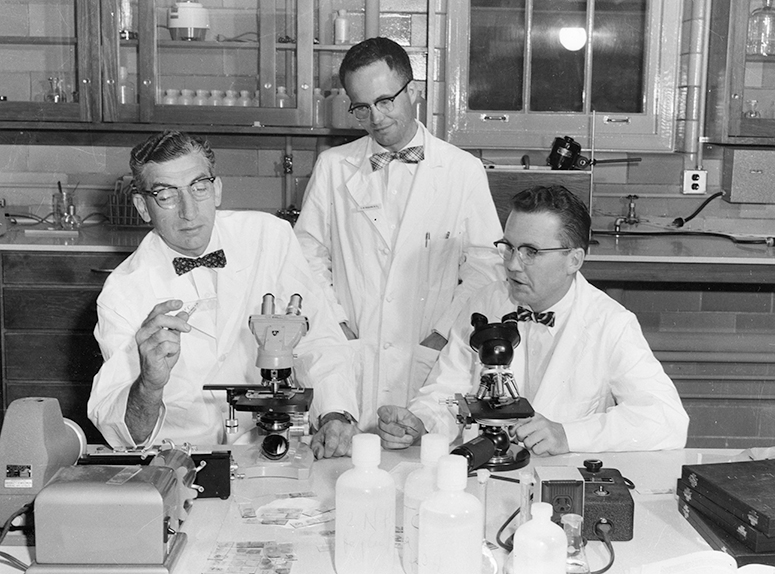

Harry Waisman ’35, MS’37, PhD’39, MD’47 demonstrated the lasting rewards when you give early help to a child.

Find out early on. Harry Waisman ’35, MS’37, PhD’39, MD’47 spread that message. He understood that early detection could change the trajectory of a child’s life, and today states across the country routinely test newborns for dozens of hidden conditions, using just a few drops of blood.

Waisman studied PKU — or phenylketonuria — a rare, hereditary condition in which individuals cannot metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine. If left untreated, PKU causes severe intellectual disabilities, but Waisman knew that — if diagnosed early — it could be managed with a special diet. He pushed for mandatory screening of infants for PKU.

“The detection of this disease is not only good medical practice; it is the professional and social responsibility of all physicians who see children,” he said.

In 1963, he began to realize his vision for exploring child development with testing and educational spaces, clinics, and more under one roof, when the UW opened the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Memorial Laboratories. Before long, the campus was selected as one of two initial sites for the study of intellectual and developmental disabilities, an effort of particular interest to the Kennedy family.

Sadly, Waisman didn’t live to see a new facility named in his honor. The Waisman Center opened its doors in 1973; he had died unexpectedly following surgery in 1971.

Waisman believed that research should lead to tangible improvements in daily life, and the Waisman Center continues to work in that spirit. In 2016, scientists identified a specific protein in whey that could lead to a more palatable diet for PKU patients.

Decades after Kay Emerson became the first patient whom Waisman successfully treated for PKU, she described the lasting bond they formed. “Even after he passed away — I know where his [grave] marker is,” she said. “I would go there just before I graduated high school, after I graduated college, just before I got married. … I’d go there and talk with him. He may not still be here, but there’s a part of Dr. Waisman that will always be in my parents’ life and my life.”

Published in the Winter 2023 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.