Hunters No More

Two UW alums are training African warriors to protect and honor the majestic animal they once killed

Leela Hazzah sits in wait. Scanning the faces of those who pass, she and an assistant search for a young man just released from jail. His crime: a killing in the African savannah.

“That’s him,” says the helper, as Kamunu pedals past on a bike.

Hazzah approaches, and a partnership begins. As they chat candidly about Kamunu’s offenses and past regrets, her vision of transforming killers into protectors becomes even more concrete.

The meeting helps guide an organization that, now in its eighth year, is making great strides in protecting African lions, one of the planet’s most threatened species. By enlisting local Maasai (pronounced mah-sigh) and other tribal warriors who were once a principal threat — hunting the animals as a source of prestige and in retaliation for livestock attacks — Lion Guardians uses an innovative approach to help the people and lions of East Africa coexist.

Founded by Hazzah MS’07, PhD’11 and Stephanie Dolrenry PhD’13, the organization is based in the Amboseli ecosystem at the base of Mount Kilimanjaro, a critical corridor that connects Kenya’s largest remaining lion population, from Tsavo National Park, with the lion populations of Tanzania. More than eighty warriors — employed as Lion Guardians — monitor approximately 5,500 square kilometers, or 1.3 million acres, of lion habitat in non-protected lands across the two countries. The ranches and rangelands of these regions support tens of thousands of pastoralists and their cattle, sheep, and goats, in addition to abundant wildlife, from wildebeests and giraffes to hyenas and cheetahs.

A Lion Primer

“They’re so beautiful and so big and just cats — they’re just like a house cat,” says Stephanie Dolrenry, Lion Guardians’ director of science. If your house cat adopted the appetite of an apex predator and could burst to speeds of fifty miles per hour, that is. More about Panthera leo, the African lion:

- Largest of Africa’s carnivores; weighs up to 500 pounds

- Only feline species found regularly in large social groups, called prides

- Primarily nocturnal

- Males guard the pride’s territory; females serve as hunters

- Prey includes giraffes, wildebeest, and zebras

- Roar can be heard up to five miles away

- In the population monitored by Lion Guardians, few live past ten years of age

- Listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species

For the Maasai, cattle represent survival and livelihood, a symbol of wealth, status, and pastoral identity, while lions evoke strength and courage. The two have mostly coexisted for millennia, but conflict is inevitable where livestock and carnivores intersect, and the herdsmen will kill to protect their animals and to gain status in their community.

“The Maasai have a love and hate relationship with lions,” Hazzah explains. “They hate them because they eat their livestock — they jeopardize their livelihood — but they also revere them because they’re powerful animals.”

Lion hunting, though illegal, is also a rite of passage as Maasai men enter warriorhood, a cultural coming of age that brings esteem and the admiration of women. The first warrior to spear a lion during a hunt is given a new Maasai lion name, a sign of prestige he carries for the rest of his life.

Between 2001 and 2011, Maasai killed more than two hundred lions in the Amboseli-Tsavo ecosystem, the equivalent of 40 percent of the population being eliminated each year. While lions kill fewer livestock than other carnivores in the region, they are disproportionately vulnerable to retaliation, and are the easiest to hunt by the traditional methods of tracking and spearing. The conflict increases as human numbers grow and wildlife habitat gives way to towns and pastures, depleting natural prey for lions and isolating their populations. During the last century, lions have lost an estimated 80 percent of their historic range.

Fewer than thirty thousand lions remain across Africa, down from half a million in 1950. As a top predator and the largest of Africa’s carnivores, lions’ presence — or absence — affects all animals and plants below them.

With the threatened species in a tailspin, Hazzah and Dolrenry saw that something had to be done.

Perfect for the Job

Hazzah had been drawn to lions as a child, fascinated by her father’s tales of listening to the majestic animals roar in the distance from the rooftop of their family home in Egypt. She longed to hear these same dramatic sounds, but her father explained why she couldn’t: Egypt’s population of lions had since gone extinct.

She was determined to help save the species, and to one day hear them roar.

Years later, in the rangelands of East Africa, her connection to lions grew stronger. Hazzah, who speaks the native Swahili of Tanzania and Kenya, had traveled there to study elephant conservation. But before setting out on her own studies each day, she would accompany a colleague on early morning excursions to search for lions.

“I found myself infatuated,” she recalls. “Lions are such an elusive animal and [studying them] was more of a challenge. I enjoy challenges.”

Enrolled at UW–Madison in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, Hazzah began studying carnivore conservation with an eye toward the dynamics within communities. She traveled to Kenya as often as possible, using breaks from coursework to conduct field research. Based in a small Maasai community, Hazzah worked to understand what drives these tribal pastoralists to kill lions and what could be done to stop the practice.

An ailing Land Cruiser helped her along. But due to her vehicle’s propensity to break down, Hazzah walked long distances to reach communities, meeting many Maasai along the way. Days were spent attending church services, helping women carry water, herding livestock, sipping cups of chai tea over conversation, and observing community dynamics.

Her little home in the middle of nowhere, as she describes it, didn’t have much by way of amenities, but it did have one important feature. “Slowly, traditional Maasai warriors started coming to my home because I was the only place with a radio. That’s kind of how I attracted people,” Hazzah says.

As she built trust with the warriors, they told stories about the lions they had killed. She listened without judgment, and they opened up more and more. In all, while working on her master’s thesis, Hazzah conducted more than one hundred interviews and numerous group conversations. The warriors spoke of their animosity toward not only lions, but also current wildlife conservation programs.

“They started telling me, ‘We feel it’s unfair, because all of the jobs are going to educated, older people, but we know the bush so well. We would be perfect,’ ” Hazzah recalls. “And I thought they were right.”

She began to offer the warriors literacy lessons, and as they learned to read and write, she saw their pride build. The wheels started to turn. What if, Hazzah thought, the Maasai warriors could use their traditional ecological knowledge to monitor and protect lions, instead of to hunt them?

“It was what they wanted, and they had all of the skills to do the job,” she says.

Hazzah had recognized early on that community participation was absent in far too many conservation programs. For a program to be successful, she thought, it must involve and benefit the people who share the land with the animals, and it must acknowledge cultural values. Building off her conversations with the Maasai and in consultation with other stakeholders, Hazzah hatched a plan. She approached the Wildlife Conservation Society for funding and, with a grant secured, set the novel idea in motion.

Merging a yin and yang of sociology and biology, in 2007 Hazzah teamed up with Dolrenry to launch a participatory conservation program. As the pair pursued their doctorates at the Nelson Institute, an interdisciplinary curriculum dotted with wildlife ecology, Swahili, and educational psychology helped foster their approach.

UW Conservationists

Along with the Lion Guardians founders, many other successful wildlife conservationists have UW connections. Among them:

- George Archibald, who received an honorary UW degree in 2004, fulfilled a longstanding dream by cofounding the International Crane Foundation

- George Schaller MS’57, PhD’62, who, as a preeminent field biologist, has dedicated more than half a century to searching for rare animals, describing them, and finding ways to protect them

- Amy Vedder MS’82, PhD’89 and her husband, Bill Weber MS’81, PhD’89, who worked with the Rwandan people to conserve mountain gorillas

Conservation Instead of Killing

The donor-supported organization began with five young Maasai warriors employed as Lion Guardians in communities with the highest levels of lion-livestock conflict. Today, across their Kenya site alone, forty guardians monitor more than one hundred lions and have documented almost three hundred of the animals.

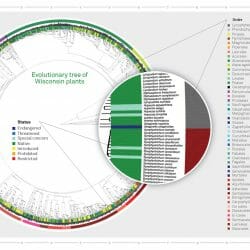

Each guardian lives and works in his home community, monitoring on foot different routes assigned each week. The guardians travel broad expanses of woodlands and grass savannahs to record tracks of the area’s primary predator and prey species: lion, spotted hyena, leopard, cheetah, wild dog, plains zebra, blue wildebeest, Maasai giraffe, and two types of antelope — common eland and lesser kudu.

They report the number of species tracked, their ages and sex as interpreted from the tracks, and the particular lion or lions believed to be present. (Lions are identified through a unique pattern of whisker spots, plus other characteristics such as ear notches or prominent scars.) Dolrenry, the organization’s director of science, uses this information to analyze lion presence near communities and species’ fluctuations over time.

If a guardian finds fresh lion tracks, he reports to base camp by mobile phone and follows the route.

The work merges the warriors’ traditional tracking techniques with twenty-first-century technologies, providing unprecedented access to an elusive species. Guardians learn to use cell phones, track radio-collared lions, and mark tracks and sightings with a GPS point.

The catch is that at the time of their hiring, nearly all of the warriors are illiterate. More experienced guardians teach the new employees how to read, write, and communicate in Swahili, and to collect and report accurate field data — skills that fill the guardians with pride. They also like to flaunt their tracking equipment; during stops in town, they sometimes act as if they’re tracking lions with a radio receiver, even though none are nearby.

“You have to smile and encourage it, because that’s part of it,” says Dolrenry. “We want them to take pride in the job so they can [say to] their peers, ‘I used to be a lion killer, but what did that get me? Now I’m cool.’ ”

Enemy Becomes Friend

Through their monitoring efforts, the guardians are able to warn herders when lions or other predators are present and help steer livestock away. Guardians also reinforce bomas, the thornbush corrals used to keep livestock overnight; demonstrate ways to better manage livestock to reduce attacks; and help recover lost animals and herders — a growing problem, as young, inexperienced children are sent to herd livestock while school and urban job opportunities draw older children away.

“These are young, young children who if left alone at night could get attacked by hyenas,” Hazzah says.

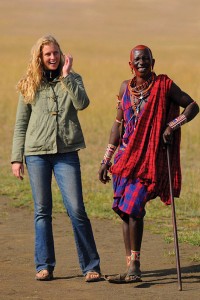

Long fascinated by — and wanting to protect — the majestic animals, Leela Hazzah (right) co-founded Lion Guardians, an organization based in the rangelands of Kenya.

The work goes toward a key tenet of Lion Guardians: preventing conflict before it occurs. By reducing the number of livestock attacks, they lessen retaliatory killings, build community tolerance, and prevent the development of livestock-raiding behaviors among lions and other predators. If livestock are killed and warriors are ready to retaliate, guardians intervene, stopping dozens of hunts annually.

“Because the majority of the guardians we’ve hired have killed lions in the past, they’re very important in the eyes of their community — very respected,” Hazzah explains.

Still, stopping a hunt often requires a guardian to face twenty or more angry Maasai warriors. “They stand in front of people with spears to stop them from killing lions. And they’re not doing that because of their salary. They’re more invested in those lions,” she says.

In their daily lion monitoring, the guardians admire the animals from afar and collect videos, photos, and stories to share with their communities. Guardians also name the lions in their area, a whimsical activity that deepens their bond, and they’re proud when lions under their watch bring cubs into the world.

“It’s something I never dreamed would have happened — these fierce warriors with kid lions,” Dolrenry says. “Now it’s like a soap opera. They want to know who’s doing what, where their lions are, and all by the lion’s name.”

The guardians demonstrate that protecting lions can preserve the warrior’s respected cultural role as defender of the community, bring prestige through employment where opportunities are hard to find, and deliver a range of local benefits. In 2014, for example, the guardians improved 481 homesteads, recovered nearly 21,000 livestock, and found all of the 21 lost children reported to them.

Keeping detailed species data is a hallmark of Lion Guardians, says Stephanie Dolrenry (left), the organization’s director of science, adding that her graduate training at the UW led to a commitment to that scientific mission.

The work has delivered results for lions, too. Since the program’s launch, lion killings have been all but eliminated in regions with Lion Guardians. And the guardians and biologists have documented a tripling in lion density in the areas of the Amboseli-Tsavo ecosystem they patrol — one of the few places in Africa where wild lion numbers are on the rise. A large percentage of cubs born in the region are now making it past their critical first two years; larger, multigenerational prides are growing in number; and new males are moving into the area, enhancing the gene pool.

Science at Work

The conservation solutions implemented by Lion Guardians are based on more than a decade of scientific monitoring. It is one of the few conservation organizations with detailed, long-term data on lions living in nonprotected, human-dominated lands.Dolrenry credits her graduate training at the UW with guiding the organization’s rigorous scientific mission.

“Learning and understanding science and how to implement it has provided the entire backbone for Lion Guardians,” she says. “We base everything on studies, and we’re very systematic about it.”

The group’s research shows that chronic livestock-raiding lions — animals that few studies have previously examined — make up less than 20 percent of the population in Amboseli but cause an estimated 90 percent of attacks. Orphaned older cubs are especially likely to turn to stock-raiding, so the organization is targeting efforts to discourage their bad behavior as they grow into adulthood.

Dolrenry also discovered that the home range for lions in Lion Guardian territories averages thousands of square kilometers — more than twenty to forty times greater than the range of lions in nearby protected areas. By helping lions roam human-dominated landscapes, she realized, the organization provides connectivity between protected populations.

“We’ve seen this over the years in areas where we work,” she explains. “Lions move out of neighboring protected areas and maybe were hunted [in the past], but now guardians and collaborators stop the hunt, and those individuals can survive and breed. Then their offspring can disperse and may reach another population.”

A cub from a Lion Guardians’ monitored area, for example, recently traveled more than two hundred kilometers north to Nairobi National Park — a journey that researchers believe hadn’t been documented for at least two decades, Dolrenry says.

But not all lion travels end well: since the group’s inception, more than one hundred lions have been killed in surrounding areas outside its jurisdiction.

More than 80 warriors have now been trained to monitor lions across 1.3 million acres in Kenya and Tanzania.

Scaling Up

By expanding its operations, building and strengthening partnerships, and sharing its model, Lion Guardians is now working to promote the movement and protection of lions across important adjacent habitats along the Kenya-Tanzania border and beyond. This is essential, Dolrenry says, because lions’ survival depends on genetic diversity, and few protected areas in Africa are large enough to support sustainable populations.

“If we can increase tolerance to allow lions to move through the landscape and breed, we’re keeping those populations viable for the long term,” she says. “That’s one of the most impactful things we can do as conservationists.”

In 2014, the organization launched the Lion Guardians Training Program, with assistance from Victoria Shelley MS’10, to train new guardians and apply the organization’s model across other cultures, species, and locales. Built on land donated by the Maasai leaders of Amboseli, the center’s construction was funded largely through the St. Andrews Prize for the Environment, one of several prestigious international awards the organization has received for its innovative approach. Hazzah was also named a Top 10 CNN Hero in 2014.

Hazzah describes herself as tenacious, and Stanley Temple, the Beers-Bascom Professor Emeritus in Conservation, remembers her determination. “She was one of the students who right from the beginning stood out,” he recalls. “Her vision, her passion, the fact that she was so single-minded about what she wanted to do, that was pretty unique.”

For the lions of East Africa, thanks to Hazzah’s foresight and the compassion of Maasai warriors, the future looks less threatening. Kamunu, the warrior Hazzah met after his release from jail, was inspired to join Lion Guardians in 2009. He has since been promoted to regional coordinator with the organization, awarded for his eloquence and leadership.

And Hazzah has achieved her childhood dream of experiencing lions in her midst, now many times over.

“When I hear lions roar, any doubt that I have, [I think to myself], ‘We’re doing it, we’re actually making a difference,’ ” she says. “It’s a constant reminder that we’re on the right path.”

Meghan Lepisto ’03, MS’04 is marketing and communications coordinator for the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. For more about Lion Guardians, visit lionguardians.org.

Published in the Winter 2015 issue

Comments

Holly Schuck January 21, 2025

Excellent article excellent effort by this young woman and the young warriors,what an inspiration!

Sammy Kiptoo February 13, 2026

The best article, very adventures and inspiring .