How to Save a Life

Mapping memories, experiences, and lessons learned.

Five years ago, Dean Olsen ’82 was wondering how to put his life back together after a period of deep personal crisis, which included two months at a homeless shelter near Madison’s Capitol Square. He had taken a job caring for a former physician with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease who was often vague and disoriented. Olsen, who’d earned his BA in geography, brought several maps to work one day, hoping they might foster some small conversation. The two sat down, by chance, before a map of Washington, DC, and the man lit up.

“He could understand the map, and his stories just started to come out: ‘You know, Dean, I used to live in Washington — I actually went to Georgetown,’ ” Olsen recalls him saying while he studied the map, tracing the city’s veiny image with his hands. “I said, ‘Why don’t you tell me about that?’ And he described, with the most coherence I’d heard in a long time, how he’d lived in this and that dorm, and then, laughing, he told me, ‘I remember being so happy to be away from my parents!’ ”

A former advertising executive who’d worked for prominent firms in Chicago, London, and New York, Olsen lost his last advertising job in a round of late-’90s layoffs. After that, his regular habit of fulsome drinking progressed to frank alcoholism, which, he says, runs in his family. (“I had my first drink at 16 and always probably liked it too much.”)

He moved back to Madison in 2006 to enter an addiction treatment program — he was then drinking about a liter of vodka a day, frequently blacking out. His sole recollection of his journey from New York to Wisconsin is that his pants fell down in the middle of the Milwaukee airport while he was switching planes for the final flight of the trip.

His parents, who’ve since passed away, agreed to pay for his rehab — as long as it didn’t take place in New York, where he’d lost nearly everything he owned, or in Olsen’s hometown of Evanston, Illinois, where they still lived at the time. Insisting on this distance was one of “the smartest things they could have done,” Olsen says now, because so many alcoholics fail to recover quickly and become abusive toward those people who’d like to see them get sober.

Olsen’s path to recovery was rocky at first: several times, he stopped drinking, only to relapse after a few weeks or months. When he was off the wagon, he alienated some members of his family and gravely worried old friends. One whom he’d known since his college days, Tim Radelet JD’80, took to boxing up his alcohol and carting it to his neighbors’ house before Olsen came over to visit, to keep him from ransacking his liquor cabinet. But after Olsen began regularly attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, he finally got the perspective and support that he needed to quit drinking. With the exception of “one six-day error in judgment” that confirmed he still cannot safely drink, he’s been sober since 2010.

“It’s the magic of AA,” adds Olsen, who is 58, widening his eyes. “Somehow, that sharing helps you feel less isolated, and it releases something, so we see each other and ourselves as fully human, with strengths and flaws. And then, together, we’re able to do something we couldn’t do on our own, which is put the bottle down. Hearing those stories from other people in the room saved my life.”

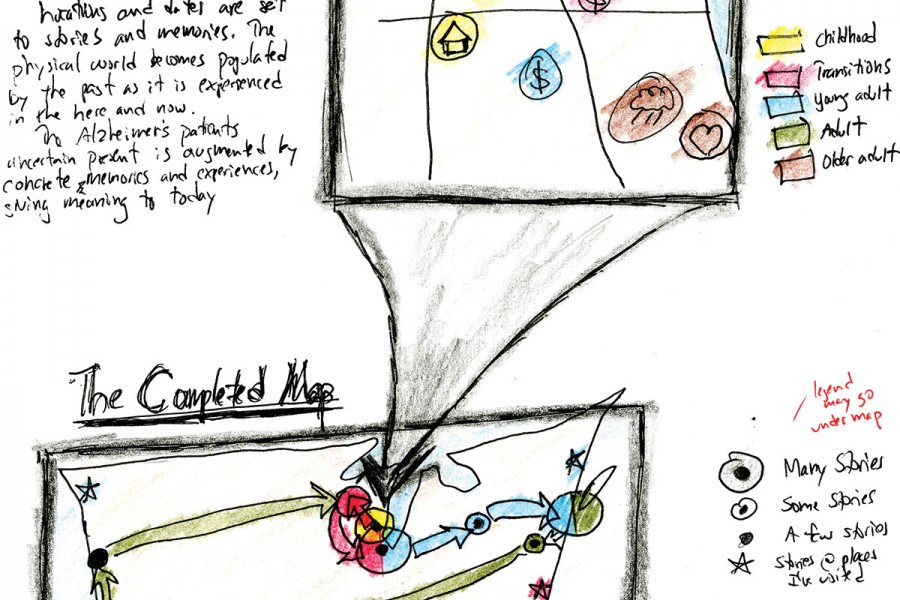

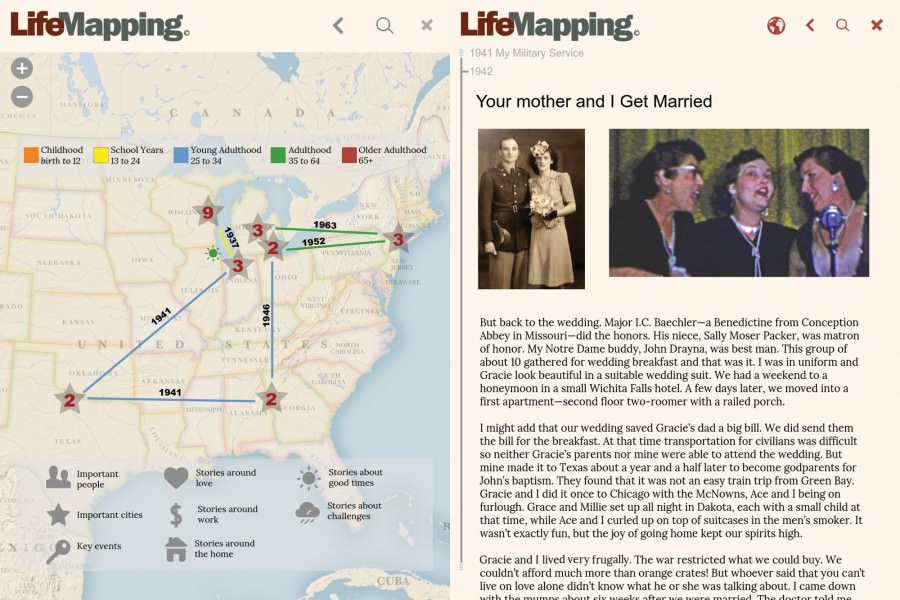

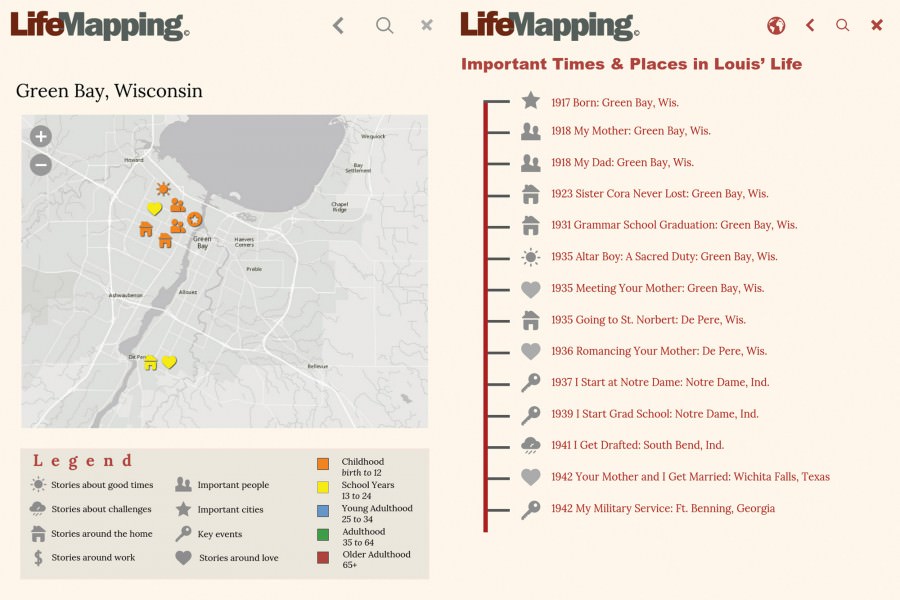

Stirred by the power of the stories he was hearing at AA meetings and thinking about the pleasure and interest his patient experienced looking over the map of Washington, Olsen had an epiphany. In his 20s, he made maps that color-coded streets according to how they made him feel. What if he could find a way to help people use maps — those beautiful triggers of memories and conversation — to capture and record their own important life stories? To create a kind of online autobiography describing different life setbacks and triumphs and plotting them on a map that people could share with friends and family? “Everything happens somewhere, so why don’t we use time and space to organize our stories?” he wondered.

It was, he realized, the seed of an idea for a tech startup. It would be understandable for a recently homeless, middle-aged recovering alcoholic with a marked stutter he makes no attempt to hide — hardly the stereotypical image of a young, fast-talking tech hotshot — to decide it would be impossible to pull off. Instead, Olsen began making sketches to flesh out his idea. A few months later, he returned, with his drawings in hand, to his old home on the UW campus, the geography department in Science Hall, to see if his idea — which he eventually called LifeMapping — had any potential.

• • •

The first time Olsen walked Tanya Buckingham ’01 through his vision for the online platform, the UW Cartography Lab’s creative director thought it was a novel and cool idea. She also thought it could help people think about maps in a new way and “reflect and make meaning of their experiences in a way that would be very different” from the disjointed manner in which we normally narrate our lives on social media.

With the help of two small scholarships and student loans, Olsen enrolled in the UW’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) certificate program in 2013, an option that, he says, seemed tailor made for him. Like many other departments on campus, geography offers a capstone graduate certificate program to help returning, mid-career professionals acquire relevant new job skills, or help nontraditional adult students retool to start a new career. Knowing that whatever he ended up doing would be, in essence, his retirement plan, Olsen used his time in the program to learn everything he could about interactive mapping, online information visualization, and cartography tools and design programs.

Olsen created an award-winning digital map to promote public awareness of drunk driving, and, working with a team of classmates, he developed an interactive map of Paris, which UW French professor Joshua Armstrong later presented to an appreciative audience at an international literary conference. (The map highlighted places where scenes occurred in an experimental 2007 novel by French author Thomas Clerc.) Olsen also dove deep into psychologists’ research on narrative storytelling, finding ample evidence to support his hunch that, when people spend time describing and writing about different chapters of their lives, highlighting the meaning and redemption of their own storylines, often their mood and view of the future improve significantly.

Eager to connect with people who could help with the business and technological aspects of developing a web-based startup, Olsen searched the UW for anyone whose work and ideas interested him. After attending a talk on persuasive mapping research by Ian Muehlenhaus, director of the geography department’s online master’s program, Olsen not only had questions, but offered some helpful feedback on teaching design — informed by his background in advertising — that Muehlenhaus incorporated into his own classes.

The idea behind LifeMapping also resonated with Muehlenhaus: “People like knowing where they stand in the big picture and seeing where they are in relation to other things. That’s why so many of us love maps — they’re a great container for our stories.” He’s also enjoyed getting to know Olsen, now a regular lunch companion. “In our very first conversation, Dean told me, ‘I’m a recovering alcoholic,’ and what he was trying to accomplish,” says Muehlenhaus. “I’m an open book, too, and I just fell in love with him and how his mind works. I think of him as a colleague as well as a friend.”

Olsen also impressed various people involved with fostering new business developments through the UW, and even though he completed his capstone certificate in 2015, he’s continued to advance his plans for LifeMapping with their support. In the spring of 2015, he won awards in two competitions hosted by the Wisconsin School of Business, earning a total $5,500 to help get LifeMapping off the ground.

Last fall, he was selected to join the School of Business’s highly competitive Discovery to Product (D2P) program, where he conducted rigorous market research for LifeMapping. D2P’s former director, John Biondi, was immediately touched by Olsen’s personal story: one of Biondi’s relatives, though thriving now, struggled for some time with drug and alcohol abuse. But his job isn’t to make funding decisions based on largesse. It was only after, at Biondi’s request, Olsen crafted a savvy Internet business model and created a smoothly operating version of LifeMapping that Biondi officially invited him into the program last fall. And after Olsen devoted more time to refining and finalizing his business plan, D2P decided last spring to invest significant startup funding in LifeMapping. It’s enough to help Olsen hire the staff needed to get the app up and running. A free beta test version will be available this fall, and Olsen anticipates the finished product will be available for sale in late 2018.

“There are a lot of apps out there that are pretty ridiculous, just redundant to what’s already out there. But Dean got my attention immediately,” says Biondi. “His background isn’t in tech; it’s in helping people make emotional connections,” which can be a challenging commercial niche, he adds. “We have great hopes for Dean and will continue to support him as long as we can and cheer from the sidelines.”

• • •

Olsen also has a strong support system in his personal life. As a recovering alcoholic, he needs to control his stress. He meditates, regularly attends concerts and talks on campus, and, lately, he’s started gardening. He has close friends, including Melanie Ramey, a former director of Madison’s YWCA, who first hired Olsen in 2014 to serve as a resident overnight-care provider for her husband, who suffered from vascular dementia. After her husband died in 2015, and knowing that Olsen was on an extremely tight budget, Ramey invited him to stay on as her housemate.

The two spar about music. (“He’s a real snob about classical music,” she says.) Olsen cooks creative meals several times a week (shopping and chopping are relaxing for him, too). And Ramey is happy to serve as a sounding board for Olsen when he runs through presentations and pitches for LifeMapping: “This kind of project involves a lot of behind-the-scenes work, stuff that takes endless hours of setting up,” she says.

Radelet is another steadfast friend. He recently helped Olsen complete a final, tablet-based LifeMapping prototype using his own late father’s life story, which, conveniently, his father transcribed before he died. When Olsen was still drinking, Radelet used to check in with his roommates and would sometimes swing by Target, where Olsen was working at the time, with no intention of purchasing anything but “just to keep an eye on him and make sure he wasn’t dead.” Today Radelet is extremely grateful for the attention and guidance the UW provided his old friend. It has enabled Olsen to, as Radelet puts it, “pull back from inside of himself the essence of who he really is: a remarkable, insightful, and sensitive man who’s had a lifetime of incredible experiences that have shaped him.”

But Olsen sees it a little differently. Yes, during the past four years, he’s gotten tremendous help and guidance from more experts than he can count across the university. He’s held brainstorming sessions with students as well as senior citizens at nursing homes to hear what different things they might want from a do-it-yourself, map-based tool for recording personal history. And recently, he has worked with staff at the Wisconsin Historical Society to get his newly completed LifeMapping prototype into the hands of a group of avid local genealogists, who’ve eagerly agreed to test-drive the program with stories they’ve unearthed about their families. However, he’s perhaps most grateful that the UW made him feel, despite his past struggles, that he, as a graduate and returned citizen of Wisconsin, “had a right to reach out to the university for information and help.”

“The UW has made a commitment to speak to people like me,” he says. “And without the university’s structure and support, I’m not sure I would have come as far as I did, all the way from a homeless shelter to the cusp of startup success.”

Louisa Kamps is a Madison-based freelance writer and contributing editor to Elle.

Published in the Fall 2017 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.