How Badgers Eat

A history of UW cuisine

My memories of UW cuisine center on cost-cutting lunch strategies, like ordering gravy over rice from the Lakefront Cafeteria in the Memorial Union, or pairing a bag of salty yellow popcorn from the Rathskeller with a 25-cent carton of Bucky Badger chocolate milk, sold out of a vending machine on the lower level of the Humanities Building. That’s right, Humanities had a milk vending machine. Bucky Badger in all his pugilistic glory was emblazoned on the side of the waxy little red-and-white carton. Welcome to UW–Madison.

The thing about being an undergraduate is, you are not usually tuned in to fine dining. Generally, undergrads have neither the time nor the money to be gourmands.

With the money I saved, though, I would reward myself with a slice of fudge-bottom pie or a Babcock ice cream cone from the Union — or better, a hot fudge sundae if I rode my bike out to Babcock Hall. And every so often, I would invest in a glass of good red wine and a slice of Queen of Sheba cake at the then-reigning monarch of State Street dining, the Ovens of Brittany.

My good friend Becky Harth ’82, who waitressed at the Ovens while in school, remembers the restaurant’s morning buns, as well as other local favorites: “Rocky Rococo slices, sprout and cheese sandwiches on grain bread, and tap beer — never from bottles.” It’s a representative selection from the early 1980s. There are beginnings of locavorism side by side with remnants of hippie dishes and the pizza and beer beloved by 20-year-olds everywhere.

Although UW–Madison doesn’t have a dish named after it, the school has plenty of reasons to distinguish it as a unique culinary zone. And besides, who wants to eat Harvard beets anyway?

In the Beginning

The first dining hall on campus was in South Hall, one of the original dormitories along with North Hall. Scott Seyforth PhD’14, current assistant director of residence life, says the kitchen was overseen by the wife of math professor John Sterling.

Many students, however, lived off campus and would have needed to find food elsewhere. Following a fire in Science Hall in 1884, North and South Halls were taken over for classroom instruction, and there were no dorms for men until the opening of Tripp and Adams in 1926. Women continued living on campus in Ladies Hall, which was later renamed for UW president Paul Chadbourne — in a kind of reprimand by President E. A. Birge, who wanted to punish Chadbourne for his lack of enthusiasm for coeducation on campus.

Off-Campus Classics

Avocado Spring Rolls

UW–Madison’s Library Mall is the epicenter of giant avocado spring rolls; they may well be unique to our campus. Unlike most spring rolls, these are the size of hefty burritos, with lettuce, rice noodles, cucumber, fresh basil or mint, slices of avocado, and add-ons loaded into a ginormous rice paper wrapping. They’re sold at three carts, but Fresh Cool Drinks has the longest lines.

The Red Brat

State Street Brats (formerly the Brathaus) is home to the red brat, a mixture of pork and beef that’s smoked and split before grilling, maximizing that crispy exterior. The sausage has been made by a number of butcher shops since its birth in the 1950s. Currently it’s made by Trig’s Smokehouse of Rhinelander, Wisconsin. The flavor is rich and almost sour, even without adding kraut.

Rocky Rococo Pizza

There have been other campus-area pizzas, from Gino’s to Ian’s, but it would be hard to overestimate the impact of Rocky Rococo, which opened on Gilman Street in 1974. The pizza was pan-style, not easy to find in those days. The name came from a character in a Firesign Theatre skit, which gave the place a touch of counterculture cred that dovetailed nicely with the campus vibe of the era. Pizzas were sold by the slice or the pie, and there was always the vegetarian option, the Garden of Eatin’. While pizza trends have changed since the mid-1970s, there’s still nothing quite like a slice of Rocky’s, the slightly sweet doughy crust playing off the mild marinara sauce, united by generous amounts of gooey cheese.

Cheese Curds

It wouldn’t be a Wisconsin Game Day without fried cheese curds, which are available, well, everywhere. The devoted turn to the Old Fashioned on the Capitol Square, whose curds crunch with a light beer batter. Chef-owner Tami Lax says she tried taking the curds off the menu during the takeout-only days of the pandemic because curds don’t travel well, but customers wouldn’t hear of it.

While no official menus or recipes have survived from this earliest era of the UW, it’s reasonable to assume students ate meals the way other Madisonians did during the period. Recipes from early residents were collected by Lynne Watrous Hamel in 1974’s A Taste of Old Madison. In the latter half of the 1800s, soups might range from those familiar today, like black bean, to a corn soup made with plenty of venison — or, barring the availability of that meat, rabbit, squirrel, pigeon, or duck.

Hamel includes a recipe for popovers from President Birge’s wife, Anna; cornmeal/pumpkin pancakes from Emma Curtiss Bascom, wife of president John Bascom; and crullers from the wife of Thomas Chamberlin, who followed Bascom as president. These doughnuts would not be unfamiliar to the decades of students who have haunted the Greenbush Bakery on Regent Street for treats fresh out of the fryer.

Desserts tended to be spice and fruit cakes or fruit pies; cookies were likely to be ginger, oatmeal, or sugar. Chocolate, that staple of today’s desserts, was not produced for the mass market until the late 1800s.

Carson Gulley: Influencer

The next era of UW cuisine begins in December 1926 with the hiring of Carson Gulley as head chef of the new Van Hise Refectory, which opened in conjunction with the first lakeshore dorms that year. Don Halverson MA 1918, then director of dormitories and commons, discovered Gulley working in a resort up north and hired him on the strength of his cooking.

Gulley was influential not just in campus kitchens, where he paid special attention to cook training, but in Madison as a whole. As an African American, he fought Madison segregation laws for years along with his wife, Beatrice, in their attempts to buy a house.

The couple encountered so many barriers that the UW built the Gulleys an apartment in the basement of Tripp Hall before they finally managed to buy a home in the Crestwood subdivision.

He and Beatrice had a pioneering cooking show on Madison television in the 1950s, and many area families and UW graduates still use his method for roasting a turkey — no basting required. Still, Gulley is most often remembered as the creator of the UW’s fudge-bottom pie: a graham-cracker-crusted, vanilla-custard-filled, whipped-cream-topped concoction distinguished by a bottom layer of intense chocolate. Some sources claim the recipe came from two chefs at the Memorial Union, and both the dorm cafeterias and the Union have served the pie for years. As its originator, Gulley wins out in popular memory, and his recipe for the pie is included in his cookbook Seasoning Secrets and Favorite Recipes of Carson Gulley.

Gulley, who died in 1962, was honored when the Van Hise Refectory was renamed Carson Gulley Commons in 1966. It’s now called Carson’s Market within the Carson Gulley Center.

The Mysterious Maizo Salad

Since the Memorial Union opened in 1928, it’s been in the business of serving daily breakfast, lunch, and supper from fast student sustenance to fine dining. For much of the 20th century, the Georgian Grill was a table-service, linen-tablecloth restaurant on the second floor, while Tripp Commons was a cafeteria-style gathering place for faculty and students (in addition to the Rathskeller and the Lakefront Cafeteria on the first floor). Ted Crabb ’54, director of the Memorial Union from 1968 to 2000, says the Georgian Grill was a “very elegant dining room” used to entertain visiting guests and was frequented by the public before theater performances. Faculty would bring their families there for dinner in the evening.

Tripp Commons often saw faculty and their students meeting at lunch, pulling tables together, and “discussing the issues of the day,” says Crabb. “There was a sense of community.”

Many Union menus from Tripp Commons and the Georgian Grill from the 1940s have been saved in the University Archives. Lunches usually included a lighter option like a sandwich or creamed chipped beef on toast, but there were also heartier entrées that could serve as dinner.

Dinners included an entrée, vegetable, fruit, roll, and beverage. Meat was the star of the show — veal, lamb, pork chops, steak, roast beef, chicken. There was the occasional inclusion of smoked beef tongue or one-offs like a chicken liver omelet with creole sauce. Global cuisine was limited to chow mein and “Italian spaghetti with meatballs and parmesan cheese.”

Crabb says the most popular meal at the Georgian Grill was steak, and the most requested dessert was fudge-bottom pie.

Salads were also in rotation. Lots of them. In addition to a spinach salad that wouldn’t be out of place in today’s dining rooms, there was “banana and salted peanut,” “devilled cabbage,” many aspics and gelatins, and some whose ingredients are likely lost to time, like a perplexing “Maizo” salad.

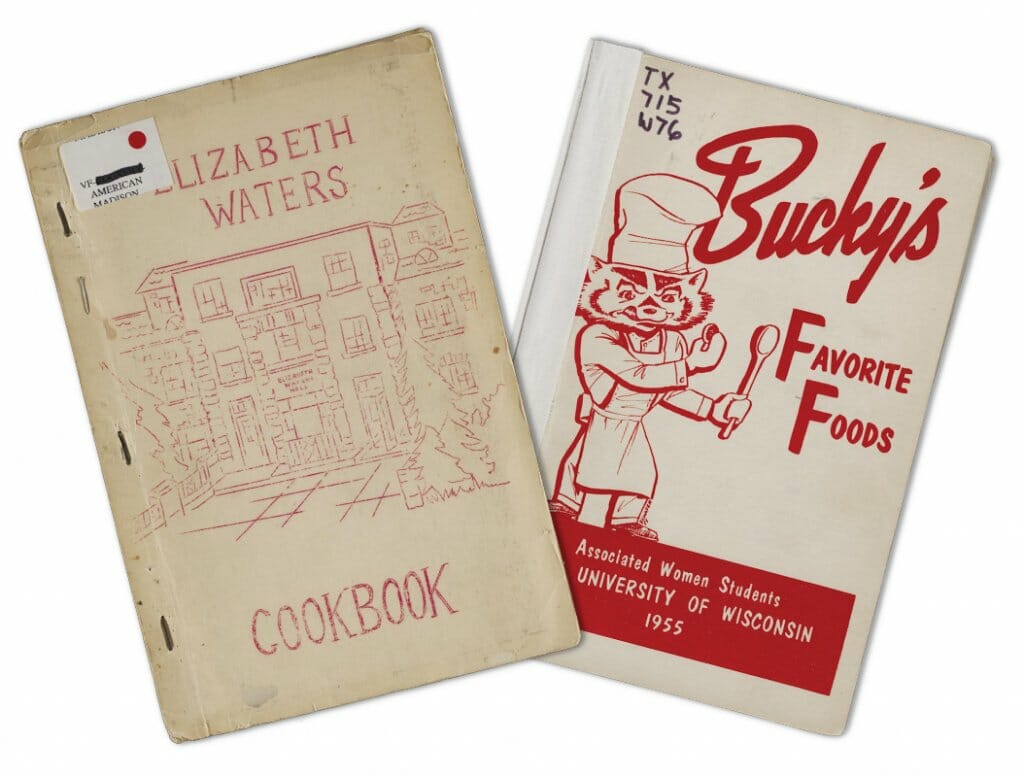

Most dishes say “1940s America” more than they say “Wisconsin” specifically, although the state’s cheeses are sometimes called out as part of a menu item. “Fresh red plum with Wisconsin cheese and toasted crackers,” “Wis. blue cheese with t. crax.,” “apple pie with Wisconsin cheese,” and “grilled Wisconsin cheese sandwich” all make appearances. The recipe for the mysterious “veal birds,” an entrée that crops up frequently in the 1940s Union menus, is included in both a 1955 and a 1965 version of a cookbook for Elizabeth Waters Residence Hall. It collected recipes “for all girls of Liz who will wish to recapture an important part of dorm life — mealtime,” as the introduction to the 1955 edition puts it. Veal birds are strips of veal steak stuffed with a bread-cube dressing, rolled, and baked.

Another milestone from midcentury was the Babcock Dairy Store, which was an innovation included in plans for the new Babcock Hall in 1950. The small dairy bar on Linden Drive was intended primarily for campus patrons, as the university did not want its product to compete with commercial ice cream producers.

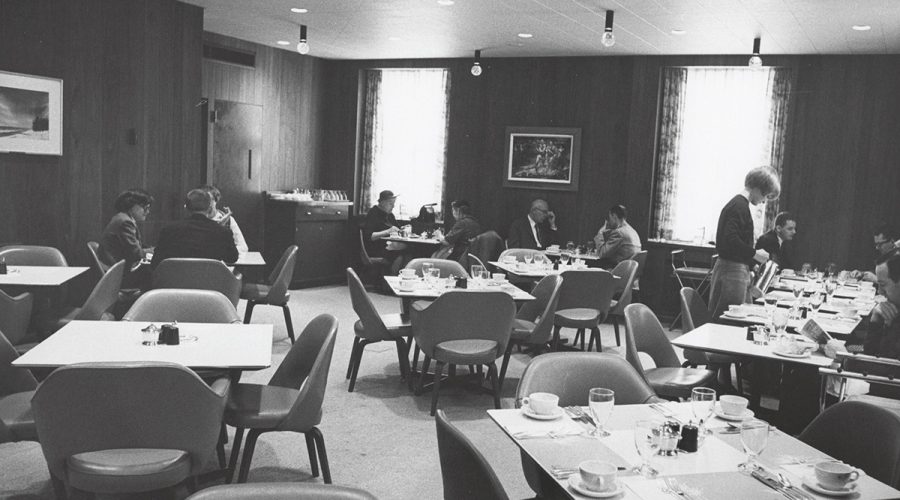

The elegant Georgian Grill in the 1960s. Meat was the star of the show. UW Archives 2017S01241

Tripp Commons in the 1960s. UW Archives 2017S01243

Bucky Badger helps out in Gordon Commons. UW Archives S08733

Babcock Dairy Store in 1981. UW Archives S09274

Comfort Food

Campus dining underwent many changes during the reign of Rheta McCutchin ’56, food service director from 1958 to 2002. In the 1970s, McCutchin was instrumental in creating an eater-friendly, à la carte model. She said the other Big Ten schools thought the UW was crazy for going to individual item choice and pricing, but the system served the university well for many years. McCutchin was also instrumental in making food available at a wider range of hours and introducing more global flavors into the menu.

When Julie Luke began working for dining services in 1985, many of Carson Gulley’s original recipes were still in rotation. “Probably up to 1995 or so, there were a lot of remnants of cuisine that started with Carson,” says Luke, who retired in 2017 as associate director.

By the mid-1990s, though, even modifying the old recipes wasn’t quite working. “That older-style food just wasn’t what the students were looking for,” Luke remembers. “But I think the basics of what Carson stood for — the quality of ingredients, his technique, his commitment to teaching students — have stayed.”

Luke says student favorites tended to be “comfort food,” like macaroni and cheese or mashed potatoes and gravy. And they were good — made from scratch.

Luke mentions a popular mint brownie from the mid-1980s. The minute the words are out of her mouth, that brownie materializes in front of me like the dagger in front of Macbeth. Dense and fudgy, it had a layer of vivid mint-green frosting. A recipe for “Creme de Menthe Bars” is included in McCutchin’s three-ring binders held in Steenbock Library, with the suggestion that green food coloring and extra mint extract can be substituted for the creme de menthe. It sure sounds like the brownie I remember. The bad news for the from-scratch crowd: its base ingredient is Pillsbury Tradition Brownie Fudge Mix.

I was unable to track down another dessert bar I think I remember from that era. It had a sweet crumb crust so caramelized it might as well have been pure brown sugar, topped with a mix of nuts, dried fruits, granola, and chocolate chips. “It was very sweet,” I tell Luke, probably unnecessarily, but she doesn’t recall the dessert. Anybody?

Personal Kitchens

Peter Testory, the current director of dining and culinary services, emphasizes the attention that his team gives to student suggestions when it comes to recipe development. “First and foremost, we continually gather student feedback,” he says. “What are the flavor profiles that they’re looking for?” This evolves constantly with each new group of students.

In the last five years, Testory has seen students looking for bolder and spicier flavors, but interest in food doesn’t stop at how it tastes. “We’ve seen a huge increase in interest in where the food comes from, what manufacturers we have relationships with, and the practices of those manufacturers,” he says. “How do they treat their employees? What humane practices do they have for animals? The whole process.”

That includes a reusable to-go container program. Students exchange a token for the container, which can then be returned to be cleaned. Upon return, the student gets a new token.

Testory sees the dining halls as being students’ “personal kitchens,” and so it is crucial to “make sure that we are in tune with what menu offerings they want.” That can mean the availability of grab-and-go items as well as plenty of options for what looks like an old-fashioned sit-down dinner. Today, boneless chicken wings are one of the most consistently popular items.

Dining areas are now called “markets,” and the choices available are like a cafeteria times four. Stations serve customizable pastas, pizza, noodle bowls, stir fries, and multiple vegetarian and vegan options like dal, black bean burgers, and tempeh with red peppers and broccoli rabe. There’s even vegan beer-battered cod for a traditional — or maybe not so traditional — Friday fish fry.

“We’re starting to see more and more interest in our plant-based vegan and vegetarian options — grain bowls, Beyond burgers, plant-based chicken nuggets and patties,” Testory says.

Yet even though the markets are full of dishes that Carson Gulley might not recognize, such as a barbecue jackfruit sandwich or imam bayildi, there are, too, daily options that could make Gulley — or most alumni — believe they’d been transported back to the campus of an earlier era. Beef sirloin tips. Mashed potatoes and gravy. Roasted brussels sprouts. Herb-crusted pork loin. Homestyle mac ’n’ cheese. And yes, even a slice of fudge-bottom pie now and then.

How to Make UW–Madison’s Fudge Bottom Pie

Ingredients

Crust:

- 4 ounces graham crumbs

- 2 ounces brown sugar

- 2.5 ounces melted butter

- Pinch of salt

Custard:

- 16 ounces whole milk

- 2 teaspoons vanilla

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- 5 ounces granulated sugar

- 2 eggs

- 1 ounce cornstarch

- 1 ounce butter (note that this is not mentioned among the ingredients in the video, but do include it!)

- 2 ounces high-quality dark chocolate, chopped

Whipped cream:

- 16 ounces heavy cream

- ¼ cup powdered sugar

- ½ teaspoon vanilla

Garnish:

2 tablespoons of shaved chocolate

Making a fudge-bottom pie with Ruthie Schommer, University Housing pastry chef. Photos by Bryce Richter

To Make the Crust

Combine all ingredients in a small bowl, by hand. Pat down into a standard 9-inch pie pan and bake at 325 for 12 minutes. Cool completely.

To Make the Custard

Combine milk, half the sugar, salt, and vanilla in a saucepan over medium heat. Whisk together cornstarch and sugar in a small bowl, then whisk in eggs. When milk mixture is at a simmer, temper in egg mixture and bring just to a boil, whisking constantly. Remove from heat and whisk in butter until fully incorporated. Strain.

Remove 8 ounces of vanilla custard and combine with the 2 ounces of chopped dark chocolate immediately; the heat of the custard should melt the chocolate.

Cover remaining vanilla custard with plastic wrap, so that the wrap is fully in contact with the surface of the custard, to prevent it from forming a skin. Refrigerate 6-8 hours or overnight before assembling the pie. Cover the chocolate custard likewise and also refrigerate until pie assembly.

To Assemble the Pie

Whip cream, powdered sugar and vanilla in a small mixer bowl fitted with the whisk attachment until light and fluffy.

While the cream is whipping, spread the chocolate custard mixture evenly onto the bottom of the pie crust.

Fold about a quarter of the whipped cream into the vanilla custard, then spread evenly over the chocolate custard layer.

Finally, top with remaining whipped cream. Garnish with shaved chocolate.

Linda Falkenstein '83 is associate editor of the Madison newspaper Isthmus, where she has long covered the area food scene.

Published in the Winter 2022 issue

Comments

Mitchell Froehlich November 16, 2022

I have fond memories of the Union’s ‘swedish’ casserole. A combination of leftover breakfast sausage, corn, and a very interesting tasty sauce. This was from the early 70’s. Have never found a receipe. Great article, brought back great memories.

Sharon Crawford Schinstock November 17, 2022

69+ years later, I still have fond memories of the brats from the Brathaus . Went there after studying at the library. Live in VA now but do wish I could go back for one more brat!

Sharon Crawford Schinstock November 17, 2022

On my previous comment it should 60 years not 69!!!

Judy Lamm Figi November 24, 2022

Carson Gulley was a friend of my dad, Paul Lamm,UW alum. Carson wanted to buy a house in Middleton where dad was president of the City Council. However locals did not want a “colored” man to live in Middleton. Thus dad put through the first open housing law in Middleton. Carson later bought a house nearby in Crestwood. I was always so proud of dad for that.

Catherine A Winkler December 16, 2022

I remember loving the peanut butter fudge bottom pie served up at Union South (and we always seemed to mess up the first piece out of the pan so that it couldn’t be served to paying customers). How would that have been flavored vs the custard recipe?

Joyce Godsey Ericsson November 23, 2024

Can’t wait to make the fudge bottom pie for my family in NY for Thanksgiving.

Am sorry my grandboys didn’t go to the UW. Two are in Boston. One at BU and one at Northeastern! And one is at Texas A&M.

Will make it again for Christmas in Austin, TX.

Mary Schumann (Schlosser) March 14, 2025

Lived in Lakeshore dorms first two years, first at Schlichter and then at Kronshage. 1969-71. Carson Gulley was our dining hall and late night source of study carbs.it felt like a best kept secret, along with the crew deck in the spring.

Caryn Lang Bowe (Rank 2) March 15, 2025

I was in the marching band in the late 80’s. The band celebrated the end of the season with a banquet at Memorial Union. At the end of each marching practice that last week we would count down to the event by chanting: “(Four) more days ’til Fudge Bottom Pie!”

Peg stousland November 28, 2025

I’m going to make the pie…my aunt , Geneva Schoenfeld, was dietitian at Chadbourne in the 40s…50’s ,etc and knew Carson Gulley.

Steve Iltis (BA ‘74 - Geology) December 1, 2025

Yay! That fudge bottom pie from the cafeteria at the “rat”was my favorite all through my years at UW. Now I have the recipe!

Thanks!