Grain of Truth

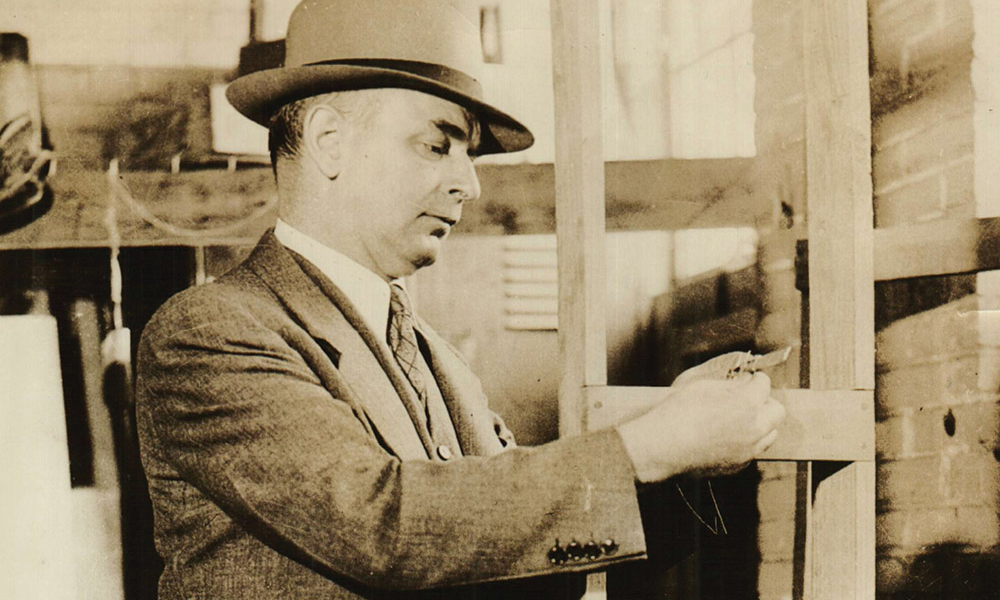

A UW wood scientist became the star witness in a trial that captivated the nation.

Arthur Koehler MS’28 first learned of the kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh x’24’s toddler son while reading the newspaper at the kitchen table in his west Madison home in March 1932. He looked at his own son, George, just 48 days older than Charles Jr., and shuddered.

What happened next put Koehler at the center of what journalist H. L. Mencken called the “greatest story since the Resurrection.”

Koehler, a UW–Madison lecturer and chief wood technologist at the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory, envisioned a “daring challenge” when he learned of the ransom note, chisel, and homemade ladder left behind at Lindbergh’s New Jersey estate. He wrote Lindbergh a letter, explaining that he might be able to trace the source of the ladder’s components and find the perpetrator.

Decades before the O. J. Simpson trial, the kidnapping and subsequent death of the Lindbergh baby gripped the attention of the American public. Koehler, who did not naturally seek the limelight, eventually helped solve the case and served as the final prosecution witness.

“I’m no Sherlock Holmes, but I have specialized in the study of wood,” Koehler told the Saturday Evening Post. “Just as a doctor who devotes himself to stomachs or tonsils … so I, a forester, have done with wood.”

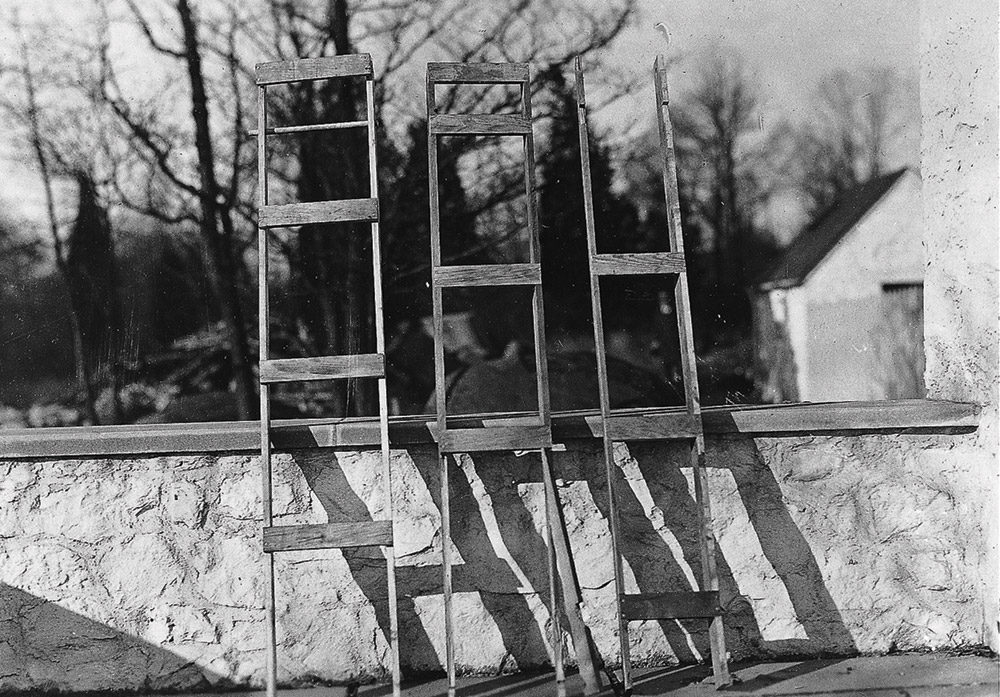

Newspapers dubbed Arthur Koehler “Sherlock Holmes” for his forensic work tracing the homemade wooden ladder (shown disassembled here) to the suspect in the kidnapping of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s toddler son. Courtesy USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, Madison

• • •

The U.S. Forest Products Laboratory was established near campus in 1909 after the UW outbid a number of East Coast schools for the federal contract. The university agreed to spend $50,000 to house, heat, power, and light what would become the world’s preeminent research facility dedicated to the study of wood.

It was at this wood mecca that Koehler arrived in January 1914, returning to the state where he grew up and where his father, Louis, tended bees and berries on a farm in Mishicot, just north of Manitowoc. Koehler’s childhood was filled with walks in the woods and countless hours in his father’s carpentry shop, where saws and hammers weren’t allowed on Sundays out of respect for some of the family’s religious neighbors. Koehler enjoyed quiet time in nature more than conversations.

He completed undergraduate work at Lawrence University and the University of Michigan and joined the Forest Service in Washington, DC, before coming to Madison to work as a xylotomist. Xylotomists often, as The Washington Post reported in 1910, needed to correct a public that frequently confused their job with those who played the xylophone. Koehler’s charge was to identify and describe wood species sent by clients ranging from U.S. Navy shipbuilders to the Chicago Cubs, who needed help when a lucky bat had broken.

His career blossomed at the lab, and he was promoted to run its new wood technology division. It’s not hyperbole to say he literally wrote the book on wood: Koehler’s The Properties and Uses of Wood was published in 1924, selling copies worldwide in a number of languages. He was the foremost U.S. expert on identifying wood species when he earned his UW graduate degree. At commencement, he shared the Camp Randall stage with Charles Lindbergh — arguably the most famous dropout in school history — who was there to receive an honorary degree.

Lindbergh first arrived on campus in 1920 aboard his Excelsior motorcycle, late for registration and his first mathematics class. He excelled as a member of the school’s rifle and pistol shooting teams and at driving his motorcycle at top speed down the steepest hills he could find in Madison. Chemistry, calculus, and English — not so much.

He left Madison on February 2, 1922, on the verge of flunking out, to pursue a career in aviation. That led to the army’s flight-training school, a route delivering the mail, and the desire to accomplish something so dangerous that many others had died in its pursuit.

Hauptmann’s lawyer told reporters that he’d “never heard more damaging testimony or seen a more enthralling demonstration than that presented in the courtroom today by Arthur Koehler.”

In May 1927, Lindbergh became the first pilot to ever fly solo across the Atlantic. As he boarded the Spirit of St. Louis in New York for the two-day flight, a reporter asked him if the five sandwiches he was carrying would be enough for the 33-hour journey. He said wryly, “If I get to Paris, I won’t need any more. And if I don’t get to Paris, I won’t need any more, either.”

When he succeeded, bedlam ensued worldwide. In the two weeks before he returned home, Lindbergh received 3.5 million letters, 100,000 telegrams, and 14,000 parcels. He launched a barnstorming tour supporting commercial aviation, flying to 92 cities in 48 states, and giving 147 speeches. He turned down $5 million worth of movie roles, product endorsements, and public appearances.

“It’s very difficult, if not impossible, for people today to fully understand the phenomenon of Lindbergh,” says Mark Falzini, archivist at the New Jersey State Police Museum, which contains hundreds of thousands of Lindbergh-related documents. “He was both a hero and a celebrity. Everybody on the planet knew who he was, and the vast majority of them worshipped the ground he walked on.”

His first child, Charles Lindbergh Jr. — dubbed “Little Charlie” or “The Eaglet” by newspapers — was born in 1930 and immediately became a seven-and-a-half-pound luminary. Any new photograph or change in diet was front-page news. Roughly two and a half months shy of his second birthday, the world felt a collective gut punch when its most famous toddler was kidnapped.

“It was a personal attack on each and every one of us,” Falzini says. “It seemed as though everyone felt violated and extremely vulnerable. After all, if it could happen to Lindbergh, it could happen to me.”

Payment of a $50,000 ransom was followed by the devastating discovery of the boy’s body. After exhausting every investigative lead from the ransom note and chisel, Lindbergh and the New Jersey State Police turned to the FBI for help analyzing the ladder. The FBI turned to the Forest Service, and, months after his letter to Lindbergh went unanswered, the Forest Service called on Koehler.

• • •

Almost a year to the day after the little boy was kidnapped, Koehler arrived on a train in Trenton, New Jersey, for his first look at the wooden witness. “If it had been the steps to a gallows, it could not have repelled or fascinated me more,” he later said.

It was a telescopic ladder, a hybrid between a stepladder hinged in the middle and a full-extension ladder, meaning it was either extendable or compressible. For Koehler’s purposes, the most telling detail was that it was homemade.

Every rung and every rail was numbered, measured, calipered for width, identified by species, and scrutinized for every mark, man- or machine-made. To determine the age of the wood, Koehler employed cutting-edge tree-ring science — known as dendrochronology — that had yet to be popularized or taught in the nation’s schools.

Today, we’ve become so used to seeing fictional forensic scientists solve crimes in the final 15 minutes of a television episode that it’s difficult to do Koehler’s subsequent 18-month investigation justice. He tracked the minute markings (to the thousandths of an inch) on the North Carolina pinewood used to make the rails in the ladder’s bottom section to a lumber mill in South Carolina. He continued following the trail to a New York retail lumber yard, only to hit a dead end when investigators learned that the business no longer allowed customers to pay with credit due to the Depression.

When Bruno Richard Hauptmann was arrested in the fall of 1934 after buying gas with one of the bills used to pay the ransom, Koehler once again joined the investigation. His expertise in evaluating the most recognizable piece of evidence in the single most scrutinized trial up to that time would be vital to the prosecution.

Using skills sharpened at the Forest Products Laboratory and shared with UW students for nearly two decades, Koehler conclusively linked Hauptmann to the crime scene. He testified that a sawed-off floorboard from Hauptmann’s attic and the wood used in the 16th rail, the upper left-hand section of the ladder, “were at one time, one piece,” which meant part of the ladder had come from inside the accused kidnapper’s own home.

The legendary journalist Damon Runyon wrote, “The tale of scientific wood and tool detection told today by a bald-headed, middle-aged man from the woods of Wisconsin … puts the greatest fictional exploits of Sherlock Holmes in the shade.”

Hauptmann’s own lawyer told reporters afterward that he’d “never heard more damaging testimony or seen a more enthralling demonstration than that presented in the courtroom today by Arthur Koehler.”

Koehler’s testimony made headlines around the country. To an early 20th-century world used to handwriting, fingerprint, and ballistic experts, forensic wood anatomy was now a scientific equal. His ability to communicate the science to the courtroom and the public at large “is a huge part of what makes the difference between broad awareness and acceptance of a body of work and that work lingering in relative obscurity,” says Alex Wiedenhoeft ’97, MS’01, PhD’08, a UW adjunct assistant professor of botany who describes himself as the academic descendant of Koehler at the Forest Products Laboratory.

“Koehler had the right chemistry for the time,” he says.

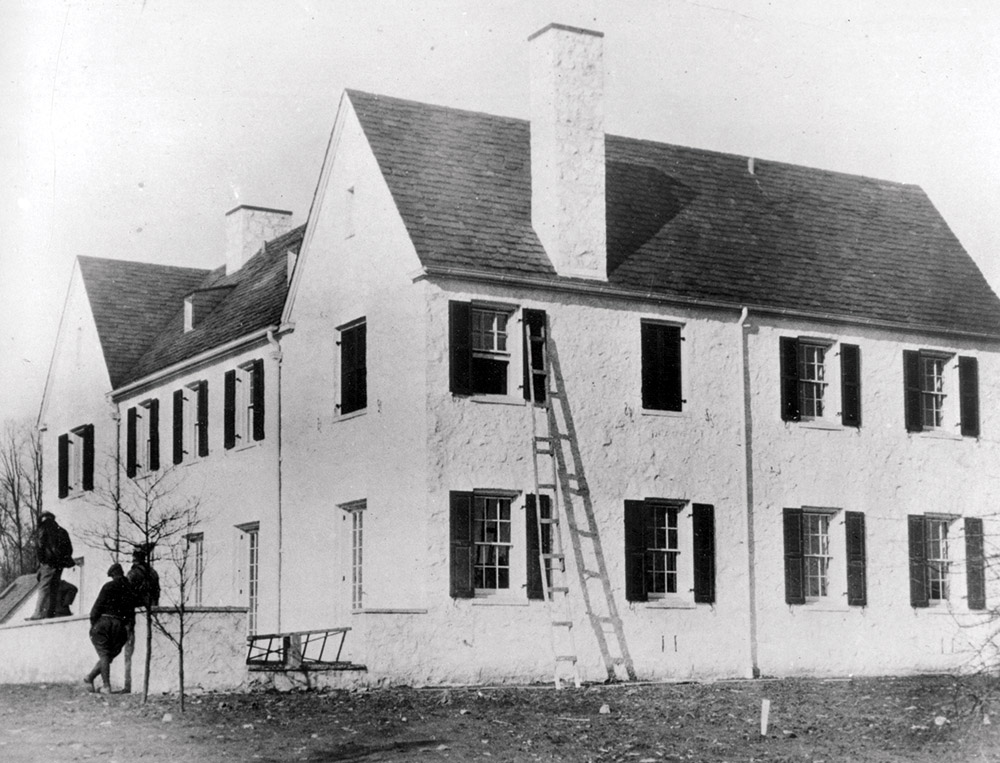

Police — shown below reconstructing details of the child’s disappearance from Lindbergh’s New Jersey estate — exhausted leads from a ransom note and a chisel found at the crime scene before consulting Koehler. AP Photo.

• • •

Even with technological advances and no shortage of conspiracy theories surrounding the Hauptmann case, Koehler’s basic science remains unquestioned by experts today.

“His work and his findings could not be challenged at the time,” says Luke Haag, a criminal forensic scientist in Arizona who used to run the Phoenix Crime Laboratory, “and would only be praised and supported today by anyone trained and experienced in the relevant specialties.”

However, besides elevating forensic botany and wood identification to an accepted scientific practice, Koehler’s legacy also highlights the flaws many scientists see in criminal justice today. His work in the Lindbergh kidnapping case is almost the antithesis of the modern forensic approach, says Skip Palenik, who runs Microtrace, LLC, and has consulted on cases ranging from the Unabomber to the Green River serial killer.

“Koehler’s effort in this case exemplifies the type of scientific work product that forensic science should be providing to the legal system,” Palenik says. “Many individuals in the criminal justice system would rather try to solve a case by consulting a psychic, a profiler, or taking a swab for DNA rather than submit microscopic trace evidence for analysis by someone who actually knows how to analyze and draw rigorously based scientific facts from it.”

At the UW, Koehler geared his class mostly toward those interested in architecture, carpentry, engineering, and manufacturing. He prepared a slide show chronicling his Lindbergh case investigation and inevitably shared the message he voiced nationwide on the radio just days after Hauptmann’s guilty verdict.

“In all of the years of my work, I have been consumed with the absolute reliability of the testimony of trees,” he said. “They carry in themselves the record of their history. They show with absolute fidelity the progress of the years, storms, drought, floods, injuries, and any human touch.

“A tree never lies.”

Adam Schrager is a journalist at WISC-TV in Madison and the author of The Sixteenth Rail: The Evidence, the Scientist, and the Lindbergh Kidnapping.

Published in the Winter 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.