UW Mysteries, Secrets, and Hidden Places

Join us on a tour of secluded spots that few have ever seen.

I often consult the alumni magazine’s archives as I research UW–Madison’s 174-year history. A while back, I glanced at the first cover published in October 1899 and was struck by the image of Bascom Hall with an unfamiliar dome. Investigating further, I learned that the dome burned down in 1916 and that charred timber can still be seen in the building’s attic.

It made me wonder about other secret spots on campus, whether remnants of past glory or hidden inner workings. Would there be any way to visit them?

It turns out there is, with special permission (and a lot of keys). So over the course of two months, photographer Bryce Richter and I crisscrossed campus to uncover the stuff of UW legend. Few people have seen these fascinating locations and artifacts — until now. Join us on an exclusive tour of the UW’s hidden places.

The Charred Attic

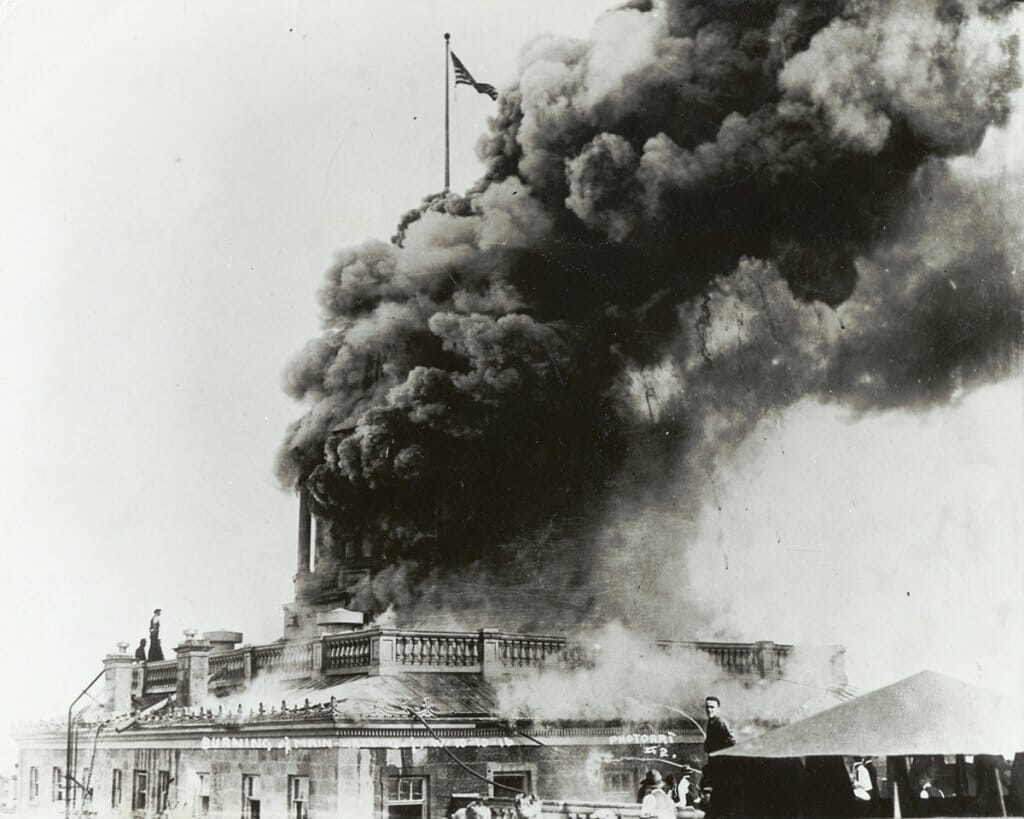

At 10:15 a.m. on October 10, 1916, a chorus of fire alarms sounded inside Bascom Hall. It’s unclear how the fire started, though early speculation faulted a cigarette butt. Regardless, by 11 a.m., flames were shooting out of the building’s ornate dome as onlookers crowded Bascom Hill. Sections of the dome started to crumble in the blaze.

Instructor Oscar Roeseler 1915, MS1916, watching from the Chemistry Building, wrote to his father that “a great sheet of flame shot through the top part of the dome. [It] seemed to lean a little, and then it collapsed, everything disappearing.”

Firefighters and volunteers confined the fire to the collapsed dome and the roof of the fourth floor before extinguishing it. The university erected a temporary roof and planned to ask the legislature to appropriate funds to reconstruct Bascom Hall’s crown. But the United States’ involvement in World War I delayed most construction efforts on campus. By 1921, reports on the project had petered out. A 1930s alumni magazine story stated that “the main structure would no longer support the erection of a heavy addition.” The dome was never replaced.

We wanted to see the charred timber that remains in Bascom Hall’s unfinished attic. You can locate this room from the outside — look for the small oval window on the front of Bascom’s portico.

Building manager Lisa Walters ’88 leads us to the fourth floor and a locked door clad with insulation. The wind rustles the creaky rafters as we enter the attic. It’s largely empty, save for some empty shelving, moisture-damaged paperwork, spare lumber, and an abandoned Reebok sneaker. The oval window, framed by student graffiti, affords a singular view of State Street. As we glance up, we see blackened rafters and beams that trace how far the 1916 fire reached.

Legend has it that the fire was finally defeated when the eight-ton dome collapsed into a large cistern beneath it. While that water tank did exist, I couldn’t find any contemporary newspaper accounts that confirm such a serendipitous event. The alumni magazine did report that hundreds of students provided “invaluable service in fighting the fire from the roof.”

A Subterranean Network

“Our forefathers who designed this were geniuses from a heating and cooling distribution standpoint,” says Edward Corcoran, steamfitter supervisor for the UW’s Physical Plant. And for him, forefathers is literal — his father, Kevin, held the same job. Who better to guide us around campus’s subterranean system of steam tunnels?

In the late 1890s, the university constructed the first underground tunnels with pipes carrying steam from central heating stations to campus buildings. With the addition of chilled water pipes to provide air conditioning, the tunnel system remains a far more efficient and economical way to heat and cool a sprawling campus compared to installing individual HVAC systems in every building.

Corcoran brings us down to the basement of the Agricultural Bulletin Building, constructed on Observatory Drive in 1899 as the central heating plant for west campus. Down here, we can explore two of the three remaining original brick-lined tunnels.

Before we enter them, we notice a massive black boiler. At the bottom of this relic are heavy steel doors where soot-covered workers once shoveled in coal by the thousands of tons to keep the campus warm. (Today, the steam system is powered by cleaner natural gas.) We then climb a ship ladder to a six-foot-high arched passage heading toward King Hall. When I touch one of the tan bricks, it releases a plume of salt.

We hear the hisses of steam and the flow of running water as we navigate through the dark, damp, narrow tunnel. A few cockroaches scatter. Although the pipes are wrapped in four inches of insulation, it’s far warmer down here than it is outside. The ambient air temperature of the tunnels can rise as high as 130 degrees, Corcoran says. We reach a diminutive door at the end of the passage, and I can’t help but marvel at the artful brick arch framing it. I see more craftsman pride down here than in many new homes.

Most of the other brick-lined tunnels have been filled in and replaced with newer concrete tunnels or smaller box conduits. The route has become more efficient, but there are still three and a half miles of walkable tunnels snaking under campus. We head over to a new segment by the Gordon Dining and Event Center that stretches to Langdon Street. By comparison, the new tunnels are remarkably clean, bright, and spacious — not that you should go exploring unsupervised. The tunnels can be extremely dangerous (the steam travels at 425 degrees and 175 pounds per square inch in gauge pressure), and entering the locked passageways is a trespassing violation. We hope our photos satisfy your curiosity.

To see how it feels down in the UW steam tunnels, check out this video.

Where Beetles Feast

Perhaps you’ve heard a rumor that six feet beneath Bascom Hill lies a climate-controlled chamber crawling with a colony of flesh-eating beetles.

That’s actually more fact than fable. The only objection you’ll hear from the keepers of this crypt is the descriptor flesh-eating. These tiny dermestid beetles can’t penetrate human skin. “They only like dried jerky,” says graduate researcher Jacki Whisenant ’11, MSx’22. But their appetite for residual meat makes them the perfect helpers for the UW Zoological Museum.

The museum keeps a catalogued collection of more than 500,000 animal specimens spanning the size chart from mussel shells to hippo skulls. Most of the specimens — including extinct species such as the passenger pigeon — are painstakingly preserved with skin or fur intact. But for research and teaching needs, some of them have to be reduced to the bones. And that’s where the beetles come in handy.

The beetles’ home is called the Dermestarium. Its unmarked exterior entrance is near Birge Hall’s Botany Greenhouse. “You wouldn’t notice it unless you were looking for it,” says museum associate director Laura Monahan ’02.

A dark hallway leads to a 300-square-foot arched brick room, where four stainless steel tanks hold the beetles feasting on the animal carcass of the day. They can reach and clean the deepest crevices of bone, finishing their dinner in a few days or weeks, depending on the size of the specimen. Other methods for precise cleaning, such as chemical maceration or boiling, risk damaging the bone.

Originally, the Dermestarium space was a magnetic observatory. The university built it in 1876 for $1,200 to conduct research for the U.S. Coast Survey. It was concealed underground and constructed with two feet of dead-air space around it to control temperature for accurate measurements of Earth’s magnetic field. The space was later repurposed for cheese curing and oil storage and as a potato cellar before the zoology department acquired it in 1950.

It’s become a perfect home for the picky beetles, which need steady warmth and humidity to survive. The museum staff members speak of them as if they were family — or roommates, as is currently the case for Dianna Krejsa. Nearby construction has temporarily blocked access to the Dermestarium, so the museum curator brought the beetles home.

“They’re on my sunporch with my plants,” she says, “with a humidifier and heater to try to keep them happy.”

The Anatomical Attic

In August 1974, graduate students in the geography department were cleaning out a room in Science Hall when they noticed a trap door to the building’s attic. Trained to be curious, they popped their heads through the opening and saw what they initially thought was a dead chicken. It turned out to be an embalmed human foot.

“[We] thought it was gross and ugly but were not horrified,” Jon Kimerling MS’73, PhD’76 told the Cap Times.

What the steely students had stumbled upon was research material from the attic’s old tenant: the anatomy department, which had moved out of the building in the mid-1950s but apparently left behind a few souvenirs. (A set of leg bones was also discovered in the ’70s and ’80s.) These stories, along with Science Hall’s undeniably spooky Romanesque Revival façade, have made the building a source of intrigue for paranormal enthusiasts.

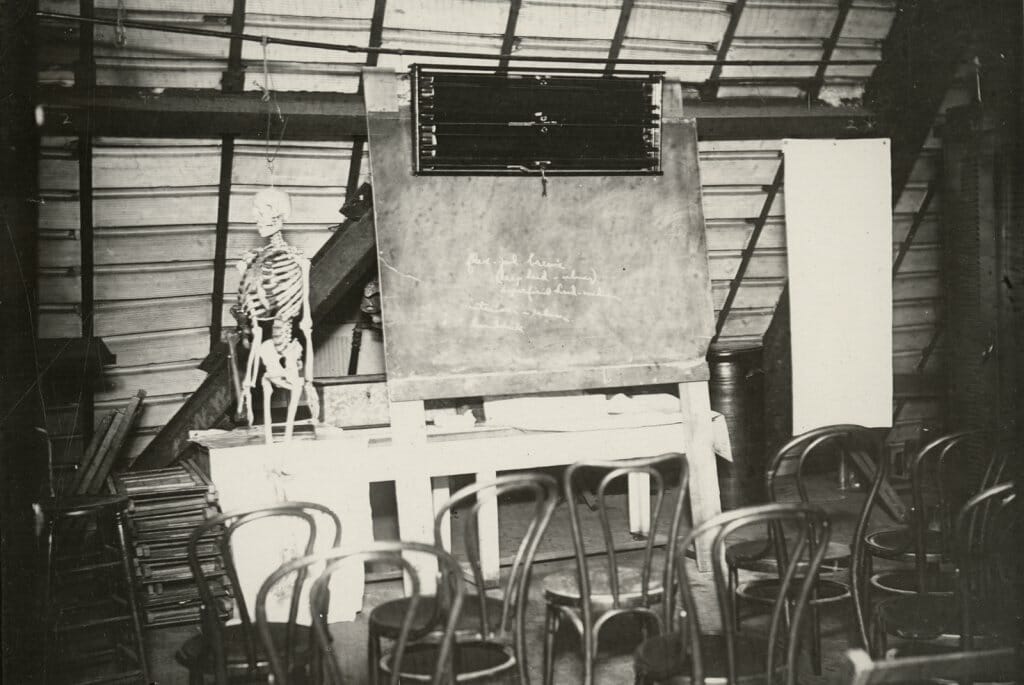

We don’t count ourselves among the ghost-hunting ranks, but we did want to explore the eerie north-wing attic that welcomed the anatomy department around the turn of the 20th century. Building manager Jay Scholz takes us up to the fifth floor via Science Hall’s antique gold elevator, unlocks a couple of doors, and shows us the deserted space.

The anatomy department moved into Science Hall’s attic at the turn of the 20th century. UW Archives S11727

After the original burned down, the new Science Hall was one of the first buildings in the world constructed largely of masonry and structural steel in 1888. Up here, we can see how the workers crudely cut the Carnegie metal before acetylene torches were available — by drilling a row of jagged holes and bending the beams until they snapped.

In the attic, you can see how the 19th-century workers who constructed Science Hall crudely cut the Carnegie metal before acetylene torches were available.

No one is sure what this space was originally used for. The anatomy department’s dissection labs were on the fourth floor, with a winch that delivered cadavers up from the basement. According to Howard Veregin, the Wisconsin state cartographer, the most famous cadaver to come through Science Hall was that of Julian Carlton, who in 1914 murdered the companion of Frank Lloyd Wright x1890 and several others in the famed architect’s home.

A 1926 alumni magazine article offers some clues to the attic mystery, profiling Professor Arthur Loevenhart’s pharmacology lab, which studied neurosyphilis.

“An unused attic in the very top of the tower of Science Hall has been converted to one of the most attractive laboratories of its kind in the country,” it reported. “Here, a number of strains of trypanosomes … are maintained, as well as a large number of animals infected with syphilis.”

We do find signs of past research activity in the attic. Three rooms contain deteriorating lab benches with old, disconnected gas lines running to them and nearby sink fixtures. I see a storage cubby with the label “Dick Bunge” attached to it. A Google search reveals Richard Bunge ’54, MS’56, MD’60 studied anatomy at the UW and became a renowned professor at the University of Miami.

But much of the mystery of this space remains.

A Theater Hidden in Plain Sight

If you’ve ever sat for a lecture in Bascom Hall’s Room 272 — as Rodney Dangerfield did for a literature class in the movie Back to School — you’ve been to the Bascom Hall Theater. If you didn’t realize it, you’re not alone: the theater’s curtains have been closed for more than 80 years.

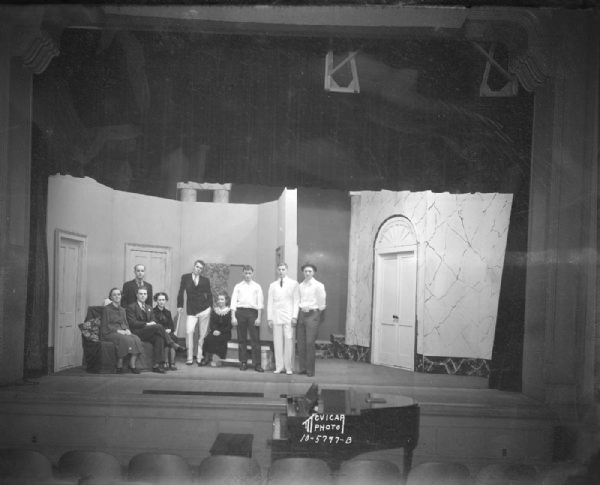

On May 18, 1927, the Bascom Hall Theater opened with a production of Outward Bound under the direction of speech professor William Troutman. Recognizing that the UW was lacking the theatrical equipment and space to host dramatic productions, the Board of Regents approved construction of a 414-seat theater with a two-story auditorium in the building’s newer west wing.

The UW’s alumni magazine called it “the finest college playhouse in the Middle West.” Troutman had even larger ambitions for the theater, labeling it “a center for the theater movement in Wisconsin” that will “endeavor to encourage new playwrights not only at the university, but throughout the state.” Students Don Ameche x’31 and Bernardine Flynn ’29 performed at the venue. (During renovations in 2020, workers uncovered graffiti with the future stars’ names.)

Bascom Hall Theater was the UW’s first theater, built in 1927 as “the finest college playhouse in the Middle West.” Wisconsin Historical Society

But by 1937, the alumni magazine was already lamenting the “inadequacy” of the theater. The much larger Memorial Union Theater opened in 1939, effectively decommissioning Bascom Hall as an arts venue. Despite a brief reopening in the late 1940s, the theater space transitioned to a full-time lecture hall.

Today, the biggest hint of the space’s history is the intricate proscenium arch that frames the lecture stage. It’s grander than you’d expect in an ordinary classroom.

But we wanted to see behind the scenes — literally.

Walters leads us to the back of Bascom Hall, through a locked and unlabeled door, to the theater’s original backstage area and fly loft. What’s now an oversized storage closet was once the command room for the university’s first theater.

Immediately, we notice the black spiral staircase leading to catwalks by the ceiling. Around the room’s brick-lined perimeter, original mechanicals are scattered among new wirings and 1980s fraternity graffiti. A slab of drywall permanently covers the area where the curtain once rose and fell.

I try to envision the earliest days here, with young stagehands frantically pulling off the university’s first major productions.

“The theater is literally being flooded with hundreds who want to act, scores who want to shift scenery, dozens who want to work props, design costumes, and paint settings,” Troutman wrote proudly in 1928.

And so they coined the theater’s slogan: “Dramatics for all.”

The Concealed Glass Dome

When Memorial Union opened its doors in fall 1928, visitors who entered Great Hall were treated to a churchly view. Suspended 25 feet above the room, a massive Tiffany glass dome sparkled with sunlight. “[The] dominating oval space in the ceiling is made of cathedral hammered glass and illuminated by a skylight above,” the UW’s alumni magazine wrote at the time.

But few visitors alive today have ever seen this work of art. The skylights leaked like a sieve, rendering the dome an instant liability. In the late 1940s, Wisconsin Union staff decided to seal the skylights, plaster under the dome, and remove its glass. If you know where to look in Great Hall today, copper detailing on the ceiling traces the dome’s outline. What’s left of the actual dome has been concealed from public view for nearly 75 years.

So we asked for a look above the ceiling.

“We don’t do a lot of tours up here,” says Paul Broadhead, the Wisconsin Union’s assistant director for facilities management. He leads us to the fifth floor, through the Marketing and Graphics Office and a thick, locked door. This surprisingly spacious attic is where Memorial Union’s mechanicals are housed. Climbing down a couple ship ladders, we reach a small metal door. Behind it lies the dome’s 400-square-foot metal frame.

The scale is still impressive, despite the structure’s dusty, rusted, and naked appearance. A small oval pattern lines the outer ring, helping us imagine the intricate glasswork that once made the dome shine. The original swinging doors for the skylights remain, though the opening is covered with plywood and roofed over. A couple sheets of plastic are draped over the dome, offering evidence of past leaks.

“What it’s really become is a structural support element for the plastered ceiling below,” Broadhead says.

There have been unsuccessful efforts in recent years to raise private funds to restore the dome, with estimates as high as $500,000. The most realistic and cost-effective approach, Broadhead says, would be creating an homage to the dome below the existing ceiling rather than attempting to reuse the original frame.

“I don’t think there are very many people left who remember it,” he adds. “The folks who are nostalgic are those who have heard stories about it.”

Madison’s Lost City

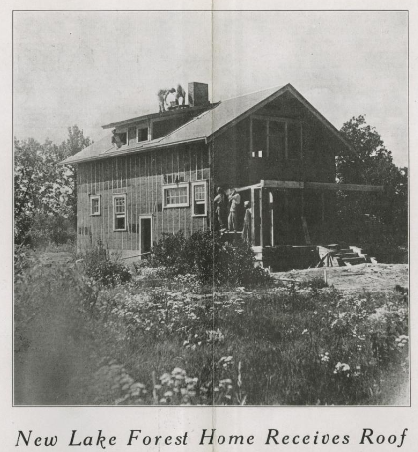

Deep in the woods of UW–Madison’s Arboretum lies the hidden history of a utopian subdivision gone wrong, doomed by human greed and swallowed up by Mother Nature. Before its remains became known as the Lost City, the planned community was called Lake Forest — “the greatest piece of work of its kind that has ever been undertaken in Wisconsin,” according to a 1920 Lake Forester promotional newsletter.

Developers Chandler Chapman and Leonard Gay indeed had a grand vision for the 840-acre Lake Forest tract off the southern shore of Lake Wingra. After years of intensive dredging to build up marshland into residential habitat, they sought to create a new type of living community — a “Venice of the North” where urban housing would coexist with spacious parks and playgrounds, spring-fed lagoons, streetcar service, a golf course, and a civic center encircled by businesses. Between 1918 and 1921, the Lake Forest Company poured roadways and constructed single-family homes.

Lake Forest was planned as a Venice of the North: “the greatest piece of work of its kind that has ever been undertaken in Wisconsin.” But all that remains of this house are crumbling concrete steps deep in the woods of the Arboretum.

But today, all that remains of that 1,000-lot planned paradise are some streets, seven still-occupied houses (many of them between Carver and Martin Streets), a brick pump station, and two large craters in the ground of the Lost City Forest.

Consumed by wilderness, the crumbling foundations within the Arboretum are well off trail and extremely hard to find. To protect habitat, the Arboretum offers only one guided tour each year around Halloween. Naturalist educator Kathy Miner ’76, MA’04 took us on an exclusive visit.

Why did the Lake Forest development fail so spectacularly? First, the terrain proved untamable, with concrete roads and foundations sinking into swampy soil. Second, World War I caused a shortage of workers and a rise in the cost of building materials, slowing construction projects. And third, the Madison Bond Company, which underwrote the whole development, defaulted after its president was convicted of mail fraud. By 1922, the development had effectively died.

Our journey to the Lost City begins on Martin Street, which extends into a public trail of the Arboretum. The concrete path, once a boulevard, is a relic of Lake Forest. Eventually, we head off trail, fight through dense thicket, and reach the concrete remains of Capitol Avenue. Now almost entirely covered with leaves and dirt but evident from its raised grading, this was to be the main diagonal roadway that led to the civic center circle and pointed straight to the state capitol.

We follow Capitol Avenue, avoiding branches and stepping over stumps, when a surprisingly square object emerges from nature. Miner climbs on top.

“I am standing on the front steps of the house that once stood at lot 14 Capitol Avenue, Lake Forest,” she announces.

Behind the moss-covered concrete steps is a massive hole with remnants of the home’s poured-concrete foundation and a matching set of back steps. A July 15, 1921, article in the Lake Forester noted of this once-standing abode: “The porches are of concrete; the house is roomy though compact; and the workmanship is excellent throughout.”

Following Capitol Avenue, we reach another set of front steps. This one is sinking unevenly, and behind it are a scattering of cinderblocks and a large, mysterious metal pipe sticking up from the ground. After Lake Forest collapsed around it, this house’s isolated locale made it a perfect speakeasy during Prohibition until it burned down in 1928.

The UW acquired large portions of the Lake Forest area between the 1930s and the 1960s after “untangling knotty legal problems,” the alumni magazine reported in 1967.

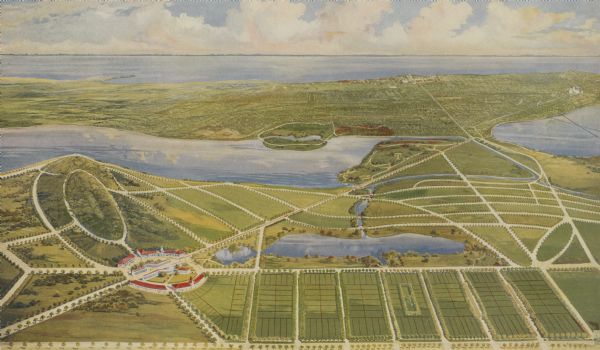

Developers had a grand vision for the 840-acre tract off the southern shore of Lake Wingra. Wisconsin Historical Society

An initiative kicked off last November to restore the Lost City Forest — now overrun with invasive shrubs like buckthorn and honeysuckle — to its original oak savanna landscape. According to land care manager Michael Hansen, you could practically see through the forest until the 1950s. But clearing the whole area could take decades, so rest assured that the Lost City will remain lost for a while longer.

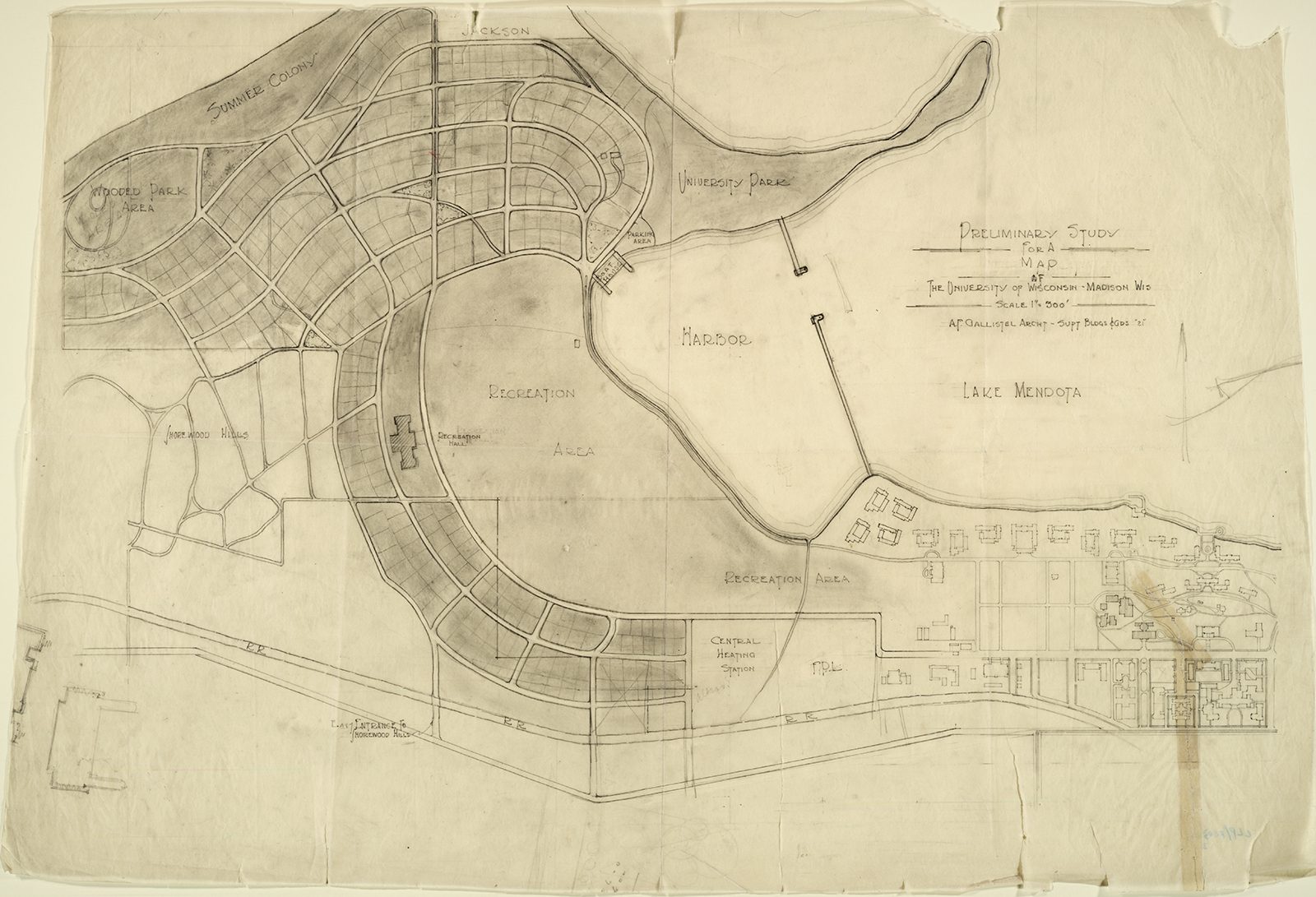

The Tent Colony

Today, a family living in a university apartment at Eagle Heights would pay at least $962 per month. In 1912, that family could have stayed on campus the whole summer for $5. There was just one catch: you had to pitch a tent.

The university’s Tent Colony — colloquially named Camp Gallistella after its beloved on-site supervisors, Albert and Eleanor Gallistel — originally popped up when a group of agriculture students asked to stay along the forested shore of Lake Mendota during summer session. The site west of Frautschi Point (now part of the UW’s Lakeshore Nature Preserve) soon turned into a popular destination for penny-pinchers, especially male schoolteachers pursuing graduate degrees during the summer with wives and children in tow. By the 1930s, there were as many as 65 tent platforms and 300 residents. The stateliest shelters featured light wood framing, tarpaper, and canvas. While the students made the two-mile trip to class by ferry boat, bike, or foot, their spouses attended to chores around camp. The kids enjoyed a classic lake life of swimming, fishing, and boating.

The camp considered itself a little city and held elections each year for mayor and other official roles, including treasurer, postmaster, athletics director, aldermen, and newsletter editor. The only comforts provided by the university were two screened and lighted study halls, pit latrines, a hand-operated water pump, and a telephone in the Gallistells’ cottage near the grounds. By 1962, the Gallistells had retired, the infrastructure had fallen into disrepair, and most married students had opted for modern amenities in the new Eagle Heights community across the road. Camp Gallistella closed for good.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that such a minimalist sect left behind little for us to see in Tent Colony Woods. Outreach coordinator Bryn Scriver ’97, MS’05 guides us through some of the Lakeshore Nature Preserve’s least-visited paths along the narrow and steep shoreline. It’s hard to imagine that this tranquil forest once vibrated with the activity of hundreds of young families. We embark on a scavenger hunt for slightly-too-square objects. Along the lakeside path, a concrete foundation marks the spot of the old well. In the woods, we find a pair of cement structures that held the outhouses. And by the shore, we locate small concrete and metal pieces from one of the swimming piers.

In the spring, visitors may notice a peculiar plant for the middle of the woods: daylilies. And that’s because Mrs. Gallistel planted them there. •