Truth, Death, and Taxidermy

Errol Morris has parlayed a lifelong fascination with universal themes into masterful films that have redefined the documentary genre.

Appropriately enough for a filmmaker preoccupied with death, Errol Morris’s office includes lifelike stuffed animals of all persuasions. Photo: Tracy Powell

Errol Morris ’69 didn’t set out to reform the criminal justice system. He was just drawn to the story of a convicted cop killer because he thought it was interesting.

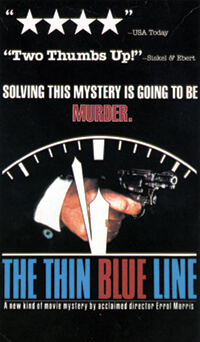

But as he researched the case of Randall Dale Adams, he began to uncover evidence that the wrong man was serving a life sentence. Adams was innocent. The release of Morris’s 1988 documentary, The Thin Blue Line, not only helped to free Adams, but also proved to be a landmark event for the so-called innocence movement.

“It was immensely important because it really gave credibility to the notion that innocent people were being convicted and sentenced to death,” says Rob Warden, executive director of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at the Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago. It’s ironic, he notes, that a filmmaker was in a better position to ferret out the truth than a legal system riddled with parochial concerns.

But that irony is perhaps less if the filmmaker is Morris, who has raised the University of Wisconsin’s motto regarding truth — its sifting and winnowing statement — to an art. The plaque on Bascom Hall that states that the university will “ever encourage that continual and fearless sifting and winnowing by which alone the truth can be found” could almost have been written as the documentarian’s personal manifesto.

Grand Themes

Morris readily acknowledges a persistent fascination with ferreting out the truth — often in conjunction with an obsession with death. Both truth and death are “absolute,” he ventures. There is no turning back from death. And Morris holds that there is always an objective, underlying truth to any situation, whether or not it is readily understood. “Truth is not relative. It’s not subjective. It may be elusive or hidden. People may wish to disregard it. But there is such a thing as truth and the pursuit of truth,” Morris proclaimed on a segment of National Public Radio’s This I Believe series. “We must proceed as though, in principle, we can find things out — even if we can’t. The alternative is unacceptable.”

Turning theoretical, Morris says, “I’ve gone to considerable efforts to try to distinguish myself from postmodernism’s [view of the] truth as being subjective. … It’s an interest that I developed probably from interviews that I did in Wisconsin years ago.”

In Standard Operating Procedure, Morris used re-enactments to examine abuse and torture of suspected terrorists at the Abu Ghraib prison. Nubar Alexanian/ Courtesy Sony Pictures Classics

Morris’s latest movie, Standard Operating Procedure, released in spring 2008, is also concerned with truth. The film uses the photos that came out of the Abu Ghraib prison in American-occupied Iraq — depicting the humiliation, torture, and even evidence of murder of inmates and detainees — to delve into the impact and meaning of photographic imagery. The director uses the images as an entry point to a larger discussion of U.S. foreign policy, message control, and the raw exercise of power.

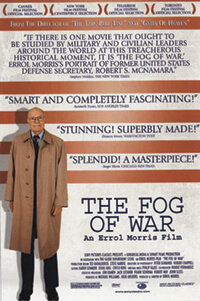

One of Morris’s biggest successes, The Fog of War, a 2003 feature-length interview with Robert S. McNamara, President John F. Kennedy’s secretary of defense and a principal architect of the Vietnam War, won an Academy Award. His first film, Gates of Heaven, is a meditation on a pair of northern California pet cemeteries, and critic Roger Ebert acclaimed it as one of the ten best motion pictures of all time. “After twenty years of reviewing films, I haven’t found another filmmaker who intrigues me more,” said Ebert. “Errol Morris is like a magician, and as great a filmmaker as Hitchcock or Fellini.”

Morris, a moose of a man with gangly limbs who now lives and works in Cambridge, Massachusetts, earned his UW-Madison degree in history. Questions about how to communicate essential truths cinematically still occupy the filmmaker today in entries he posts to Zoom, his blog at the New York Times Web site.

However, one might be forgiven for thinking that someone who sits for an interview in his office under the watchful gaze of a stuffed stork does not take himself too seriously. The large, lifelike yet lifeless animal seemingly hovers on its windowsill perch just behind the conversation. Across the room is a stuffed horse’s head with a long neck, mounted on the wall reaching up to a 25-foot-high ceiling with industrial skylights. A chimpanzee head under glass sits on the desk.

“I just like having it. I mean there’s taxidermy in the house. My wife likes it,” explains Morris matter-of-factly. Many of his dead creatures came from Deyrolle, a shop in Paris where he shot a television commercial for Cisco Systems. “I wish I had bought more,” he muses, adding that the shop was a favored haunt of surrealist painter Salvador Dali.

Cast of Characters: Ed Gein

A few years after graduating, Morris returned to Wisconsin to pursue an interest in serial killers. He began with Ed Gein, who was then an inmate at what is now the Dodge Correctional Institution in Waupun. The notorious prisoner had become a folk legend for killing several people and for exhuming bodies from cemeteries in and around Plainfield, where he had lived on his family’s farm. Not only did Gein (pronounced geen, with a hard g) dig up corpses, but he also used principles of taxidermy to fashion body parts into gruesome trophies. Gein also ate human flesh.

“Ed Gein is one of the proverbial great monsters,” Morris explains. “He, in many people’s views, originated the whole genre of psycho killer movies of the sixties.” His case inspired films ranging from Psycho to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Though Gein was arrested in 1957, he didn’t come to trial until 1968, when Morris was a UW student. The notoriety of the case increased dramatically when Gein was acquitted by reason of insanity.

By the early seventies, Morris was doing graduate work in philosophy at UC-Berkeley. He decided to write his thesis on the insanity plea, and secured a letter of introduction from the head of the School of Criminology to the superintendent at the hospital where Gein was incarcerated. Morris traveled to central Wisconsin, where he moved in with Gein’s former neighbors and conducted several interviews with the man himself.

“One truly surreal experience,” recounts Morris, was discovering that the superintendent “was as crazy as anybody I was talking to in the hospital.” His perception was cemented by a conversation in which the head of the institution insisted that Gein was not truly a cannibal, because even though he ate people, by Gein’s own account, he didn’t enjoy it. “Oookaaaay,” Morris thought to himself. “I was entering into a sort of strange, surreal world of Looney Tunes.”

Not necessarily to his own surprise, Morris liked Gein. “I found him really strange and funny, perverse, ironic — not stupid. Crazy, but not stupid,” says Morris.

Discovering along the way that Plainfield had been home to an unusually high percentage of murderers, Morris set out to write a book on the small village. “I never brought it off, which is unfortunate,” he says, “but I accumulated endless hours of interviews, hundreds of them.” Those 120-minute Sony cassette tapes are still sitting in a trunk safely tucked away in the basement of Morris’s office. “I think it’s some of my best work,” he adds ruefully.

Though he hasn’t yet been able to coax a coherent product out of that period of his life, the lessons he learned have stuck with him. “I developed a keen appreciation of how crazy the world really is — not only how crazy, but how people are endlessly misperceived by others,” says Morris. Real-life murder mysteries taught him that “you can talk to five or six people about an event that they have all experienced, and the accounts are so radically different.” That epiphany, combined with a strong feeling that “there is a reality,” helped define the person Morris is today. “People may be interested in avoiding [reality] or rearranging it, or obfuscating it, but it’s there in the wings,” he says.

At the same time as he was following his self-described “prurient” instincts in central Wisconsin, Morris was also becoming deeply enmeshed in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society in Madison. “It was an extraordinary resource,” he says of the trove of prints that included thousands of movies from Warner Brothers, RKO, and a number of Hollywood’s so-called Poverty Row studios. He began viewing films there as a student and then returned after graduating. “You could go into a room with a Kodak Pageant projector and start watching movies — you could program your own film festival,” he says. “You could select a director like William Wellman and watch thirty Wellman films, or, if you wanted, you could watch Howard Hawks or John Ford.”

Morris cites the many hours he spent cuing up classic films in Wisconsin, and also at the Pacific Film Archive at UC-Berkeley, as seminal experiences on his path to becoming a filmmaker. He also credits the many people in Madison who were deeply interested in film and in some way attached to The Velvet Light Trap, an academic journal founded by UW graduate students in 1971. “My whole interest in movies comes out of the University of Wisconsin,” he says. “There is a history to be written about all the filmmakers that have come out of Wisconsin — there’s a lot of them.”

Morris’s time in the movie archives gave him a lens through which to direct his curiosity. “I’ve always been interested in certain kinds of ideas,” he says, “and film seemed a way to actually think about stuff.”

Flashback to Long Island

A native of Long Island, New York, Morris arrived in Wisconsin in 1965 after having struggled through The Putney School, a small, arts-oriented boarding school in Vermont where he played the cello, an instrument he still practices for two hours a day. He recalls being the only member of his high school graduating class of about forty who didn’t get into a single college that he applied to. The ignominy was even greater because several of his classmates were off to Harvard. “I was waitlisted at Haverford and then rejected,” he laughs, “as if they had finally come to their senses.” His placement counselor suggested the University of Wisconsin as a last-ditch effort, and it worked. “I thought being sent to the University of Wisconsin was some kind of a punishment,” he says, “but I found out otherwise.”

The campus “had this odd, incendiary mixture — I often describe it as Wisconsin farm girls and boys, and Jews from New York,” he says. Morris, who soon became such a devoted Badger that he discussed with friends whether he should have the university’s Numen Lumen seal tattooed on his chest, credits the campus with helping him blossom intellectually. “I came into my own there in so many, many ways,” he says. “I learned to write, and I developed my interest in history. … Little did I know — which I know now, of course — is that Wisconsin had one of the best history departments in America.”

Aside from reveling in classes taught by professors such as the late William Appleman Williams, George Mosse, and Harvey Goldberg (whose lectures on social history packed in more than a thousand listeners), Morris developed a passion for rock climbing. He explored Devil’s Lake State Park, about an hour north of Madison, which he describes as some of the best terrain in the country for the sport, which was not nearly as popular then as it is now.

He wrote a guide to Devil’s Lake, which he distributed to friends, some of whom fondly recall Morris’s exploits. Alan Rubin ’67 muses, “Climbers tend to be eccentric, and much more so those of us who climbed in the sixties and seventies than is the case today. And those of us who were climbers in the flatlands of the Midwest were more eccentric still, yet even amongst this company of eccentrics, Errol stood out as a true eccentric.” He rarely tied his shoes, and he tended to wear a white shirt and necktie for climbing.

Rubin describes a certain macabre humor that characterized many climbers. For instance, Morris and two friends who collectively dubbed themselves the Terrible Trio Mountaineering Club would tick off the names of their rock-climbing heroes when they were contemplating a new challenge, noting with each name that the person was dead. “Most of us shared the same sense of humor, but Errol was the most out there with it,” says Rubin. Morris admits to cutting classes during college to go rock climbing, including taking a number of marathon thirty-hour road trips to Yosemite National Park in California.

The Plot (and Resume) Thickens

It took Morris much of the next two decades after graduating to find his footing as a filmmaker. His 1978 debut, Gates of Heaven, had little commercial success, but it earned him recognition among his peers and found a durable champion in Roger Ebert. Before making that movie, he had two false starts as a graduate student, one studying the history and philosophy of science at Princeton, and the other at Berkeley. He lived for a period in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he earned money writing term papers and master’s theses for struggling students. “I wrote a paper on the Immaculate Conception for a nun. … But I probably shouldn’t go into detail about that,” he chuckles, admitting to the potentially felonious nature of that enterprise.

Morris’s second movie, Vernon, Florida (1981), featured the eccentric residents of a swamp town. Newsweek’s David Ansen wrote that it was “the work of a true original,” and dubbed it “philosophical slapstick philosophy.”

Morris released his second movie, Vernon, Florida, in 1981. It is an almost aggressively mundane series of lengthy interviews with elderly residents of a Florida panhandle town, during which they tell strange but plausible stories. After that, Morris supported himself by working for a high-end private investigator in Manhattan, looking into, among other things, securities fraud. Upon reflection, Morris sees “an enormous connection” between that job and his proclivities as an interviewer. “Basically, the ability to function as an investigator is the ability to talk to people, to listen to people, to have people talk to you, to investigate detail, the same damn thing I do anyway,” he says.

He struggled through most of his thirties to get the money to start and then complete The Thin Blue Line, which centered on Texas prisoner Randall Dale Adams and his struggle to overturn a wrongful conviction for the murder of a Dallas police officer. “It was unendingly difficult. … Very few people stood by me,” says Morris. And yet his fortunes were soon to shift when, within days of releasing that film, he won both a Guggenheim Fellowship and a MacArthur Fellowship, often referred to as the genius award.

Much of Morris’s work reflects his interest in unusual, if not decidedly weird, subjects. Fast, Cheap & Out of Control is an intricately edited intertwining of four men’s incongruous careers. Mr. Death is a deep look into the work and personality of Massachusetts native Fred Leuchter, Jr., who was a sought-after technical expert on capital punishment before lurching off into the world of Holocaust denial.

Morris also made a television series called First Person, consisting of sit-down interviews using what he calls the interrotron, two teleprompters networked together so the interviewer and interviewee are looking at live images of each other as they speak. Subjects for this series included Sondra London, who has spoken and written extensively about her romances with two serial killers, and Temple Grandin, a noted autistic woman and university professor who happens to have designed the slaughterhouses where more than half of American cattle are put to death. Morris still hopes to make good on a pledge he made to Grandin to play cello serenades for cattle wending their way toward doom.

Morris has also made hundreds of television commercials (the irony that the medium does not lend itself to making truth its highest value is not lost on him) for companies such as Apple, Nike, Cisco Systems, and MillerCoors (High Life beer). It is highly paid work that he counts on to support his overhead, which includes a small staff, offices with four digital editing suites, and other tools of his trade.

Flash Forward: Iraq

These days, a conversation with the filmmaker is likely to turn to Standard Operating Procedure. The film centers on a small swath of the more than two hundred hours of interviews he did with American soldiers who participated in the scandal that erupted in 2004 when photos taken in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq became public. Among them are the now-famous images of Private First Class Lynndie England holding a leash with a naked Iraqi man crouching at the other end, and Specialist Sabrina Harman smiling broadly and giving a thumbs-up in front of the head of a corpse packed in ice. Through his interviews with England, Harman, and a number of their compatriots, Morris discovered that those photographs tell stories that are far more intricate and complicated than what initially meets the eye.

Errol Morris directs “I Dismember Mama,” part of a television series called First Person that featured Morris’s trademark quirky interviews. This particular episode dealt with the efforts of a cryogenics buff who sought to preserve the head of his deceased mother. Nubar Alexanian

“This film has really shaken me up — I caused myself a lot of trouble” by making it, says Morris, “because I am wandering into a kind of nightmare, where I’m trying to say something that I think is different and not necessarily what people want to hear.” He humanizes people who have been cast as monsters in the public mind, and ends up discovering that “they are like you and me.” The difference, he says, is that “they found themselves in the middle of a kind of nightmare that was created around them.”

The ire he has experienced has taken many forms, including reviews that accuse him of being sympathetic to torture. “People got angry,” Morris says. “I may be wrong about this, but I think it’s a product of being interested in unappetizing stuff; it’s a product of being interested in pariahs, which goes back to my earliest attempts to interview anybody.”

Ed Gein featured prominently in Morris’s early forays into getting pariahs to talk to him. Morris readily acknowledges the thread that runs from central Wisconsin through his latest film, and his abiding interest in painting nuanced and textured pictures of people who are easily caricatured as monsters. Being misunderstood goes with the territory. “Part of me is a dyed-in-the-wool investigator-slash-interviewer,” says Morris. He admits that his relentless quest to know things that are often unknowable takes a toll. In spite of his many accolades, Morris says, “I feel like a thwarted artist and probably always will.”

Freelance writer Eric Goldscheider is working on a book about a wrongful conviction in Massachusetts.

Published in the Spring 2009 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.