The Mysterious Mastodon

A UW curator digs into the past and discovers Wisconsin’s famous fossil wasn’t quite what it seemed.

In a black-and-white photograph bearing the fade of age, five men stand in a deep pit. Four of them are clad in workmen’s clothes, while the fifth, standing slightly in front of the others, is dressed in a bow tie and vest. In his right hand, stretching from shoulder to knee, is a massive bone with a large chunk missing from one end.

That bone, the femur of an ice-age behemoth, would become the smoking gun.

The photograph first arrived at the UW’s Geology Museum a decade ago, brought in by a curious visitor hoping to learn the whereabouts of the old bone. The visitor’s ancestor owned the now-gone farm where it was found more than a century ago, and the photo had survived the ages.

But museum staff lacked an answer; their only collection of similar bones belonged to the Boaz mastodon — perhaps Wisconsin’s most famous fossil. Based on the ages of its bones, it was thought to represent one of the last mastodons standing in the Midwest after the glaciers retreated from the Great Lakes region. A feature of the museum since 1915, the ancient skeleton has helped put Boaz, Wisconsin, on the map. A historical marker erected in 1995 sits at the site where the mastodon remains were found.

Carrie Eaton, curator of collections, helped solve the mystery of the UW Geology Museum’s Boaz mastodon skeleton. UW Geology Museum

Yet words handwritten on the back of the photograph offered a clue: “Hole where mastodon bones were discovered on the farm of J.W. Anderson in the 1890ties [sic] at Anderson Mills, Wisconsin. I am not sure but that may be my Grandpa Anderson standing in the hole holding the large bone. Pictures from W Paul Dietzman grandson.”

More photographs, also inscribed by Dietzman, documented a treasure trove of mastodon ribs, vertebrae, teeth, and much more. There was little doubt that the elephantlike creature from the Pleistocene — the geologic time period encompassing the most recent ice age, which ended 11,700 years ago — had been found on the farm, around the same time as the Boaz discovery. But the bones in the photos were nowhere to be found. And that femur, with that large piece broken off, was distinctive.

For years, the bones remained a mystery.

• • •

In 2013, Geology Museum curator Carrie Eaton MS’04 was hungry for a good project. She realized the museum was two short years from the centennial of the Boaz mastodon’s mounting — first at Science Hall and later moved to its current location at Weeks Hall — so she embarked on what she thought would be an easy journey to reinvigorate its story. She could not have been more wrong.

“This whole project started off as this tiny little thread that I started yanking,” she says. “And the sweater kept getting bigger, and I just kept pulling and pulling, and we discovered more, and it got more interesting and complicated.”

Early on, Eaton enlisted the help of David Null, director of the UW Archives, which catalogs the vast array of files, books, photographs, and other rich materials that preserve the university’s long and storied past. Together, the two began digging through boxes heavy with records: accession ledgers, correspondence among university leaders, geology department scrapbooks, newspaper clippings, and more.

They came upon minutes from a May 1900 meeting of the UW Board of Regents, which noted a request for $250 for “the purpose of properly mounting a mastodon’s bones now belonging to the University.” But in June, the motion was voted down, and the record of the mastodon went quiet for more than a decade, with the bones lying somewhere in the bowels of Science Hall, forgotten and collecting dust.

In October 1913, C.K. Leith 1897, PhD1901, chair of the geology department, wrote to E.A. Birge, then dean of natural history and the College of Arts and Sciences, asking that $500 be allotted to mount “the mastodon remains found in Richland County which for years have been stored in Science Hall.” Boaz is located in Richland County.

Leith was following up on a letter to Birge written by Maurice Mehl, a recently hired paleontologist who wanted to mount the remains, in part to promote his field. “The work of restoration here in the [geology] department will do much to arouse interest among students and others in paleontology,” Leith wrote. “It is peculiarly fitting also that the Geological Museum should have an actual representative of one of the big animals that formerly roamed through this part of Wisconsin. It should be of considerable interest to visitors and to the state.”

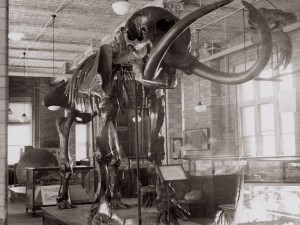

The UW’s mastodon, seen in Science Hall in the 1940s, marked its 100th year on display in 2015. UW Geology Museum

Eaton and Null kept digging, and they soon found a letter, dated July 29, 1898, from Birge to the regents. “The heavy rains of last week washed out portions of the skeleton of a mastodon on a ravine not far from Fennimore, Wisconsin,” Birge wrote. The Anderson farm was located near Fennimore, about thirty miles southwest of Boaz. “I directed Mr. Buckley, Assistant on the Geological Survey, to go down … and investigate the matter. He found a considerable number of bones and purchased them for $75. … The price which he paid was moderate, as the bones are worth, at a low estimate, three times as much as those for which the Department of Geology paid $50 last year.” The only entry recording a purchase of a mastodon — for $50 — referred to bones from Boaz, which Eaton found in the geology department ledger dated January 1898. But the university, it seemed, paid for two different sets of mastodon bones.

The letter also noted that Charles Van Hise 1879, 1880, MS1882, PhD1892, a geology professor who later became university president, was interested in “accumulating enough” bones to “make a complete skeleton,” indicating a willingness to combine mastodon bones for one display.

The yellowed letters represented a pivotal moment for Eaton. They suggested that the Boaz mastodon — standing proud all those years in the museum — might actually be a composite from multiple creatures. She and Rich Slaughter, director of the Geology Museum, knew that pulling out the old Dietzman photographs was a critical step.

What they discovered next took Eaton’s breath away.

• • •

If the Boaz mastodon was more than one mastodon, how would Eaton be able to link the bones to where they were found? After she looked over the skeleton and noted some differences in the size, shape, and staining of some of the bones — caused by the organic elements under which the bones had lain for nearly 12,000 years — Eaton realized the femur in the photograph could be key to solving the puzzle. If she could only find that funny fracture.

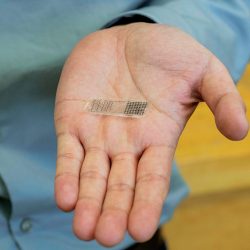

A CT scan revealed that a break in the mastodon’s femur matched the one from the old photograph taken at Anderson Mills. UW Geology Museum

One hundred years earlier, the bones had been restored in plaster and painted, so finding the break would take some creativity, and some science. Eaton enlisted the help of museum scientist Dave Lovelace and staff at the Wisconsin Institutes for Medical Research, who ran the femur through a CT scan, a type of medical x-ray that would allow her to examine the natural features of the bone. While viewing the three-dimensional, black-and-white image of the massive thigh, Eaton gasped, realizing that the fractured bone — the one in the old photographs from Anderson Mills — was the very one she had removed from the Boaz skeleton in the museum.

To verify her findings, Eaton sent small bits of material from telltale bones on the skeleton to labs in Arizona, Massachusetts, and Ontario, Canada.The samples were dated by measuring the age of decaying carbon, and their genetic identities were checked, ensuring that they were bones from a mastodon, not from a mammoth, a similar ice-age creature found throughout the Midwest.

Eaton also tracked down E.R. Buckley’s field notes from Boaz. According to university correspondence and historical newspapers, Buckley — the man sporting the bow tie and vest in Dietzman’s photos — was at the scene of both mastodon discoveries. His sketches from Boaz revealed that few bones were recovered there on behalf of the university. There were so few, in fact, that they could not account for the seventy real fossils that make up the mastodon on display. (The rest of the mastodon is replica bone.)

Today, Eaton and museum staff have rewritten the story of the Boaz mastodon, demonstrating that the town’s famous creature is, in fact, two animals found by farm children a year apart in southwestern Wisconsin. While she has not yet located an Anderson relative, the museum has heard from the Dosch family of Boaz, whose members are excited by the renewed interest in “their mastodon.” And an officer of the Fennimore Railroad Historical Society Museum, which has two bones from the Anderson Mills find on display, has told Eaton that he and the bones planned to visit the museum soon.

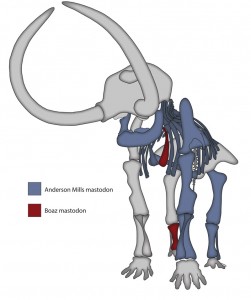

UW’s mastodon is a composite made from bones discovered in two Wisconsin communities just thirty miles apart (shown below in red and blue) and sculpted replicas (in gray). UW Geology Museum.

Like Leith before her, Eaton wants to inspire Wisconsinites by teaching more about the megafauna — from giant beavers to stag moose, caribou, and mammoths — that once roamed the Badger State. Along with Geology Museum assistant director Brooke Norsted MS’03 and a team of undergraduates, Eaton spent the summer of 2015 giving library presentations throughout Dane County, and in the fall, they opened a new exhibit at the museum featuring these giant creatures.

“They roamed all over the Midwest, and it’s really neat that these were found in Wisconsin,” she says. “It’s an opportunity to teach people about something they’ve never heard of — that this is their natural history.”

Kelly April Tyrrell MS’11 is a science writer for University Communications.

Published in the Spring 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.