The Hunt for Answers

Are there too many deer? A UW scientist says reducing the herd will help our forests.

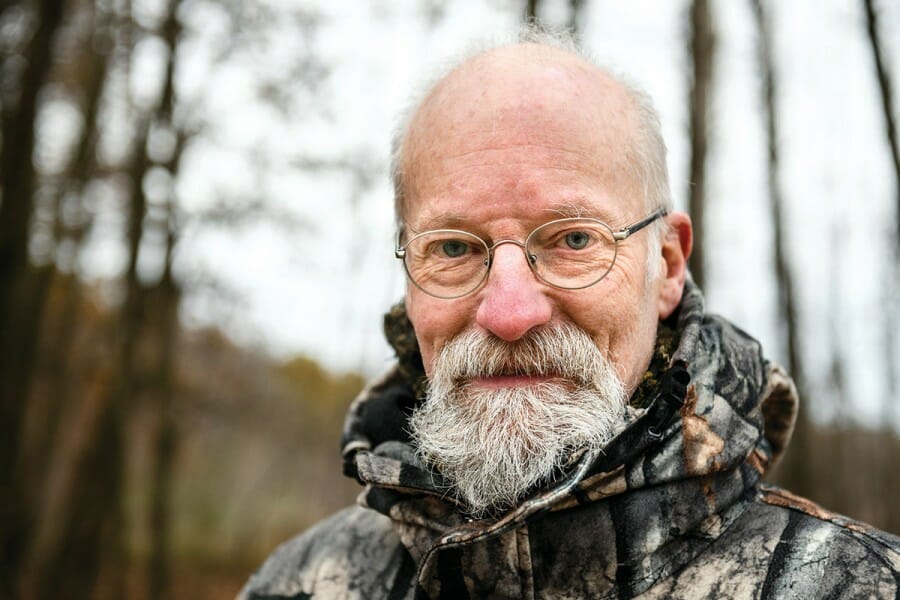

Don Waller first saw them near sundown: a wall of whitetail deer, coming doe after doe through an abandoned apple orchard about 15 miles west of campus. In many ways, Waller was well acquainted with these animals, having tracked their numbers and effect on the state for decades. In other ways, it was an introduction. He had never been so close to a deer — let alone a dozen — before he clambered into a tree stand in October 2011.

Waller had long documented how deer are eating trilliums and other wildflowers close to extinction and devastating white cedar, hemlock, and oak saplings across much of Wisconsin. His research has helped to show that the huge number of deer in recent decades is throwing the natural world off balance. But in spite of all that, Waller was still not expecting to see so many deer so quickly.

Up the trunk of an ash tree, the then 58-year-old scientist seemed about to succeed on the first hunt of his life. Following in the footsteps of Aldo Leopold — a UW professor and hunter who had also warned about deer impacts — Waller had for years been urging state officials to let hunters harvest more deer to blunt the animals’ effects. For Waller there was a powerful logic to what he did next: he drew his bow.

The image of an archer aiming at a clearing full of deer might seem more a part of Wisconsin’s past than its present. But there’s never been a better time to be a deer hunter in this state — and many other parts of the nation — than the past several decades. Wildlife experts think that, in recent years, the country’s whitetail herd has been as large or even larger than the one that existed before white settlers arrived two centuries ago. The landscape of Wisconsin has been upended since then. In northern Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where Waller has focused much of his research, old-growth forests have given way to young forests, edge habitat, and farm fields that are far more favorable to whitetails.

Deer rely on the forest’s understory and the plants that they can reach to survive. But towering trees block the sunlight and limit growth on the ground. Logging, fires, and anything else that clear the way for sunlight and undergrowth in a forest provide more food for whitetails. Add farm fields and row crops, and suddenly deer have enough food to reach densities that Wisconsin’s native peoples might not have imagined.

Scientists estimate that when white people first arrived in Wisconsin, the northern forests of the state held four to eight deer per square mile. As a result of human intervention, there are now roughly 15 to 30 deer per square mile in parts of northern Wisconsin, and double that in some middle and southern counties. The same challenge extends to many other parts of the country.

In Virginia, state wildlife officials estimate that deer densities in Fairfax County parks — not far from Washington, DC — have reached more than 100 animals per square mile. Scientists in New York and Pennsylvania have turned up ecological impacts from whitetails as well, prompting groups such as the Nature Conservancy to argue that high deer numbers may pose a greater threat to forests in the eastern United States than climate change. As adults, each of Wisconsin’s 1.3 million deer will eat more than 2,000 pounds of food a year. Profound ecological damage can result, as Waller saw firsthand on a 1987 trip to northern Wisconsin.

One of his research collaborators, William Alverson ’78, PhD’86 had convinced Waller to drive up that summer from Madison to Foulds Creek State Natural Area near Park Falls. The two were looking for a small, fenced-off section of woods. They wanted to examine the plants inside the roughly 20-year-old “exclosure” — so named because it excludes deer. Waller thought the fence would be difficult to find in the forest — it was anything but. Hiking in, the two men saw their destination from far away.

“You can’t really see the fence from a distance. You just see the green,” Alverson says.

Within the fence, whitetail favorites such as hemlock and northern red oak thrived. Outside the wire, those plants were absent or stunted — a stunning difference. At the time, wildlife managers still sometimes argued that deer had no environmental impacts. Waller could see at a glance that wasn’t true.

“It converted me instantly into a believer,” he says. “It made me realize, ‘Wow, we need to pay more attention to this.’ … I had assumed up until then that the experts knew what they were doing.”

David Clausen reached a similar, but much more costly, conclusion of his own about damage from deer. A retired veterinarian familiar with Waller’s work, Clausen once served as chair of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Board, which helps oversee wildlife and environmental policy in the state. Twenty-five years ago, Clausen planted roughly 50,000 oaks on land he owns in the northwest part of the state. Today only a handful of those trees remain — deer helped kill the rest. Most of the surviving oaks are less than three feet tall and have the strange, undersized appearance of a bonsai tree.

“I became aware of just how much having that excess of deer on the land had cost me,” Clausen says.

To restore his land, Clausen would like to remove invasive species such as buckthorn — a small tree that deer won’t eat — and plant other, native species like aspen. But he sees little point to doing that if deer are going to kill the plantings. Many oaks still tower over Clausen’s land, dropping acorn crops each fall that nourish deer, squirrels, and turkeys. But as the trees succumb to wind and old age, he worries about whether they’ll be replaced.

“You can’t have a sustainable forest if you can’t get regeneration,” he says.

Leopold made a similar observation in the years just after World War II in his landmark work, A Sand County Almanac. In the essay “Thinking Like a Mountain,” Leopold describes how the land had suffered after he and other wildlife managers had exterminated wolves in western states. In the Midwest, deer numbers had yet to rebound fully, and few were imagining any potential fallout from them. But before moving to Wisconsin and writing that essay, Leopold lived and worked in the American Southwest, where he saw how the loss of wolves contributed to an overabundance of deer that damaged the landscape.

“I have seen every edible bush and seedling browsed, first to anaemic desuetude, and then to death. I have seen every edible tree defoliated to the height of a saddlehorn,” he wrote.

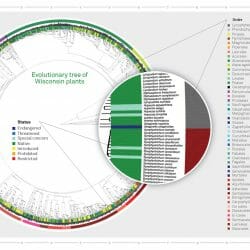

Decades later, Waller and his colleagues found those impacts and more: a cascade of effects on plants, other animals, and even the soil itself. The scientists built their own exclosures and also did surveys to compare current plant populations in parts of Wisconsin to those documented in the 1950s by UW professor John Curtis and his students. They found a startling result: deer accounted for at least 25 percent of the changes they observed in plant composition over the past half century. Whitetails didn’t just stress some native plants and make room for invasive species — they shifted the makeup of whole plant communities toward species with unpalatable or tougher leaves. Deer also compacted the soil, altering the composition of its upper layer. By changing the plants in the understory, deer also affected the other animals and birds that rely on them.

In addition, big numbers of deer can lead to more auto accidents, more of the ticks that carry Lyme disease, and a faster spread of threats such as chronic wasting disease (CWD), which attacks the nervous system of deer and causes them to lose weight and eventually die. The misshapen protein that causes CWD hasn’t been shown to affect humans, but concerns over it are leading some hunters to avoid certain areas or give up the sport entirely. That in turn could make it harder for the remaining hunters — already an aging and dwindling group — to keep the herd in check. Nationally, the number of hunters dropped 16 percent from 2011 to 2016, according to a national survey released by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Census Bureau. The level of hunting in 2016 was the lowest measured in the past 25 years.

There are other obstacles to preventing deer impacts. In deciding how many whitetails are too many, the DNR has traditionally looked at the populations in large geographic areas. But deer numbers and impacts on local plant communities can vary widely across these big zones, and the measurements aren’t necessarily meaningful at the local level, says Alison Paulson PhD’18, who worked with Waller as a graduate student.

Paulson and Waller’s other collaborators, including Sarah Johnson PhD’11, a Northland College professor, want scientists and wildlife managers to pay more attention to these differences and are investigating methods for easily monitoring deer impacts. They’re working in iconic places such as the Apostle Islands in Lake Superior and Leopold’s land near Baraboo, which was featured in A Sand County Almanac and is now held by his family foundation.

Not everyone is listening to Waller’s warnings. He found that out in the early 1990s, when he tried to convince DNR officials to reduce the deer population over the objections of hunters.

“I was told point blank that it was politically unfeasible,” Waller says.

George Meyer, the DNR secretary from 1993 to 2001, says that sounds plausible, though he doesn’t recall ever speaking with Waller about it. Meyer, now the executive director of the Wisconsin Wildlife Federation, a conservation group of hunters and anglers, says many deer hunters loved the large herd sizes of that era and opposed lowering them.

“If you had talked to a wildlife manager back then, I’m sure you would’ve heard that kind of statement,” Meyer says.

In states including Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Indiana, it’s common to see state wildlife agencies come under fire from hunters if the deer population dips below record levels. In his time on the DNR board, Clausen also saw how hard it can be to convince others to thin the herd. “A lot of people don’t understand what the deer herd is doing and, frankly, a lot of them don’t care,” he says.

Clausen has been hunting deer for nearly 60 years — he took his first buck while Dwight Eisenhower was president and deer were less plentiful. He thinks that hunters who came of age in recent decades have grown accustomed to easier hunts.

“It’s a matter of perception,” he says.

Waller and his research team haven’t been content to document the loss of biodiversity — they’ve tried to stem it. Waller and other researchers sued the U.S. Forest Service in 1990, seeking to force it to set aside large swaths of mature forest without the kind of cutting that ends up providing food for deer and boosting their numbers.

“If you want to hang onto things that love old-growth forest, you have to think about that,” Alverson says.

Though the lawsuit failed, Alverson believes it helped change the thinking of many land managers. In recent years, Waller’s been looking for other ways to shift people’s thinking about what it means to have healthy forests and a healthy herd. He decided to become a hunter, for instance, in part to understand hunters better. To do that, he says he had to overcome some of his own preconceptions.

“I sort of assumed people were into [hunting] for the bloodsport aspect of it,” says Waller, who began to discover other reasons why people hunt, such as access to lean, organic meat.

He also got pointers on pursuing deer with a gun from Tim Van Deelen, a UW professor of forest and wildlife ecology and former DNR manager who read Waller’s work as a graduate student and found himself fascinated by its insights. The two men have since collaborated on research.

“Having been a deer specialist my whole career, [Waller] is one of the important voices out there,” Van Deelen says.

For his part, Waller’s several years of hunting have given him an appreciation for its challenges. He has helped to field-dress a deer but has not yet taken one himself. One of his closest moments to success remains that first hunt. The problem that day was, ironically, that there were too many deer. With all those does and yearlings below his tree stand, Waller couldn’t draw his bow — too many eyes were watching. After a long wait with no opportunity, he finally felt compelled to pull back his bow. As he did, the deer below caught the movement and scattered like marbles struck by a taw. Waller never had time to shoot.

When Jason Stein MA’03 isn’t writing, he likes to hunt deer and share the meat with family and friends.

Published in the Winter 2018 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.