The Best of Barry Alvarez

Set to retire, the athletic director picks his favorite moments from a legendary Badger career.

In a 12th-floor suite at Tokyo’s Miyako Hotel, Barry Alvarez surveyed the rivers of neon light brightening the bustling metropolis below.

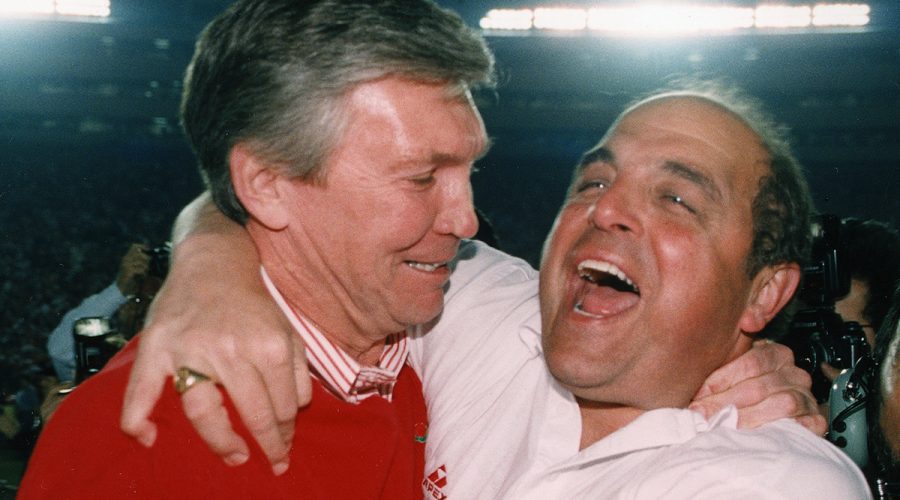

It was hours after the Badgers capped his fourth season as football coach by defeating Michigan State 41–20 in the Tokyo Dome in December 1993. The team had captured Wisconsin’s first Rose Bowl berth in 31 years.

“We’re going to the Rose Bowl,” a grinning Alvarez said. A belly laugh welled up as he shook his head in amazement. “It’s ridiculous.”

Alvarez and his team had just engineered a turnaround that propelled a college football laughingstock to long-lasting success.

Twenty-seven years later, the view from his Kellner Hall office window is just as impressive. It offers Wisconsin’s athletic director a panoramic view of Camp Randall Stadium, today one of football’s iconic venues — thanks in large part to Alvarez’s leadership. His pride in 31 years of accomplishment at Wisconsin is palpable.

“I’m proud of the culture we’ve built,” says Alvarez. “That’s allowed us to be one of the country’s most consistent programs. You go from never going to a bowl game to going every year; from never being in the NCAA basketball tournament to doing it every year. That’s our culture.”

Alvarez’s coaching career spanned 16 seasons and produced three Rose Bowl victories. He transitioned to a remarkable run as athletic director, resulting in major facility improvements, 74 conference championships, 16 national team championships, and 25 individual titles.

In April, Alvarez announced that he would retire this summer, signaling the end of an era for Badger athletics. What are the highlights of his Wisconsin career? Fans will debate that question for years to come, but here are the top picks from the man himself.

An Era Dawns

After a disastrous three-year run that ended in a 6–27 record, former chancellor Donna Shalala and newly appointed athletic director Pat Richter ’64, JD’71 turned to Alvarez to return the luster to Wisconsin’s moribund football program.

Richter traveled to Miami, where Alvarez, Notre Dame’s defensive coordinator, was preparing for the 1990 Orange Bowl versus top-ranked Colorado. While Alvarez was in a pregame meeting, Richter called his hotel room and got his father.

“Pat told my dad he was going to offer me the job, and my dad broke down crying,” Alvarez recalls. “When we ended the staff meeting, dad pulled me over and was still crying. My dad never got very emotional.”

Notre Dame won the game, and celebrations lasted until 3 a.m. Alvarez got two hours of sleep, then boarded a plane bound for Madison and a McClain Center news conference announcing his hiring.

“I was running on fumes. Late in the press conference, I said, ‘I’m sorry. I’m just fried.’ I was emotionally zapped, and the adrenaline just ran out,” Alvarez says. “Just an incredible day.”

Legitimacy at Last

After three years of methodically building a football program as coach, evangelist, and ticket-seller, Alvarez led his team to Pasadena in 1994. On a postcard-brilliant day, the Badgers achieved legitimacy with a 21–16 Rose Bowl victory over UCLA.

“We were on our way, and the fans finally had something to cheer for,” Alvarez says.

And there were plenty of fans — about 70,000 of the stadium’s 101,237 seats were filled with red and white.

As players stretched on the field before the game, Alvarez asked, “Doesn’t Camp Randall look lovely today?”

None of it would have been possible without Alvarez’s first recruiting class, assembled quickly and with an emphasis on in-state athletes. It included running back Brent Moss x’95, receiver J. C. Dawkins ’95, and defensive lineman Mike Thompson x’95.

A salesman visiting Alvarez’s uncle at his grocery store in Pennsylvania touted Joe Rudolph ’95, an offensive lineman who ended up on Alvarez’s roster — and who today is the Badgers’ associate head coach under Paul Chryst ’88.

“I told those guys that I’d always be indebted to them because they bought in,” says Alvarez, whose teams returned to Pasadena to score back-to-back victories in 1999 and 2000. “They had so much to do with what we’ve accomplished.”

A Life-and-Death Situation

At the north end zone of Camp Randall Stadium, giddy triumph turned to tragedy on the way to the 1994 Rose Bowl. Moments after Wisconsin defeated the Michigan Wolverines 13–10, a railing broke under the crush of students eager to storm the field.

The uncontrolled rush left dozens injured and the Astroturf strewn with helpless fans turning blue from a lack of oxygen. Many players, including Moss, Rudolph, and Joe Panos ’94, helped free people from the heap.

“It looked like a war zone. Our guys thought they were carrying dead students out of there,” Alvarez says. “I had gone up the tunnel when things started. I saw Joe Rudolph come up and he was crying. I said, ‘Rudy, you’re that happy?’ and he said, ‘Coach, there’s dead people out there.’ ”

Fortunately, no one died, but 69 people were hospitalized, four in critical condition.

Walk-on receiver Mike Brin ’96 saw an injured student bent over a fence. Brin grabbed her by the leg, hauled her into a stadium tunnel, and made sure she was breathing and conscious. Then he helped two other victims by administering mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Today, Brin is an emergency room doctor.

“When you see how your student-athletes respond in a life-and-death situation, it’s awfully impressive,” Alvarez says.

The Dayne Game

They called Ron Dayne ’17 the “reluctant hero.” Soft-spoken off the field and a battering-ram running back on it, Dayne was the center of attention as the Badgers played Iowa on November 13, 1999.

It was Senior Day at Camp Randall, and Dayne was 99 yards from becoming college football’s all-time leading rusher. The buildup for the game was unprecedented, and fans in the stadium waved white towels bearing Dayne’s name and number — 33.

“The atmosphere for that game was second to none,” Alvarez says.

With less than five minutes left in the first half, quarterback Brooks Bollinger ’03 handed the ball to Dayne on a play called “23 Zone.” Dayne cut back in the hole gashed open by the offensive line, juked defenders, and picked up 31 yards to break the record before a roaring crowd. He went on to amass 216 yards, help lock up a Big Ten title, win the Heisman Trophy, and embark on an NFL career.

“I don’t care where I go; when I run into a fan, they usually bring up the Rose Bowls or Ronnie’s game,” says Alvarez.

Eighteen years later, Dayne graduated from UW–Madison. He credits Alvarez for prodding him to get his degree. “When we recruit, we tell families that we want kids to walk out of here with a degree, a meaningful degree, from a world-class university,” Alvarez says.

A Special Way to Go Out

Few believed Wisconsin could prevail in Alvarez’s final game as coach in the 2006 Capital One Bowl in Orlando — except the Badgers. Alvarez’s friend Bob Davie, the former Notre Dame coach and TV broadcaster, warned him privately that number-seven Auburn was unbelievably talented. Boosters told Alvarez they felt sorry for him because his last game was against Auburn. Even his wife was doubtful.

“We finished a pregame news conference and Cindy said, ‘You did a great job. The media down here loves you, but you’re probably going to get beat,’ ” Alvarez recalls.

With that negative feedback, Alvarez pointedly sold his players on the idea that it was a great matchup and that they could win. On the Badgers’ last full practice day — dreaded by players because of its intensity — Alvarez gave them the day off, something he’d never done.

Wisconsin defeated the Tigers 24–10, ending the game with a kneel-down at the Auburn one-yard line.

“They went in with a great attitude and the belief we could win,” Alvarez says. “The way the guys played was amazing — a pretty special way to go out.”

A Big Win for Women’s Hockey

The Badger women’s hockey team skated to a national championship in 2019 at the People’s United Center in Hamden, Connecticut, defeating border rival Minnesota 2–0 for the fifth NCAA title of coach Mark Johnson ’94’s career. The others came in 2006, 2007, 2009, and 2011, plus another this year.

Though Alvarez couldn’t attend the game, he took particular pride that day in how Johnson and his athletes forged success.

“He has such a nice manner, and it’s obvious that the women love playing for him,” Alvarez says. “That’s hard to do, year in and year out, without some complacency. They are so productive and successful and consistent.”

Johnson, a star on the USA’s “Miracle on Ice” team that won Olympic gold in 1980, was feted as part of the 40th anniversary of the achievement. “For all of us to be able to relive that moment and honor him was so exciting and meaningful,” Alvarez says.

Final Four Fever

For Alvarez, winning is meant to be savored. “I tell everyone: don’t ever take success for granted. Winning is hard.”

That’s one reason the 2015 men’s basketball season, in which Coach Bo Ryan’s Badgers went to the NCAA title game against Duke, stands out for Alvarez. “For a long time, we didn’t experience tournament games, let alone playing for a national championship,” he says. “When you’re part of that, and you’re there for the shoot-around and a part of the inner circle, that’s fun.”

The Badgers, who made it to the Final Four in 2014 but lost to previously unbeaten Kentucky 74–73 in the semifinal game, came back to defeat the Wildcats 71–64 to advance to the marquee game. But Duke proved too much for the Badgers at Indianapolis’s Lucas Oil Stadium, defeating Wisconsin 68–63.

The game was a pinnacle for Wisconsin basketball, which under Stu Jackson went to the NCAA tournament in 1994 for the first time in 47 years. Alvarez notes that Dick Bennett followed up by fashioning a winning tradition that took Wisconsin to the Final Four in 2000. Ryan built on that foundation.

“There’s no better basketball coach than Bo,” says Alvarez. “The guys knew exactly what he wanted, and they delivered. He could play a lot of different ways, but his swing offense was effective. And they played good defense.”

Alvarez calls the 2015 squad a close-knit, fun-loving group. After the game, a downcast Frank Kaminsky ’15, the nation’s college player of the year, said: “These guys are my family. … It’s going to be hard to say goodbye.”

Some Real Coaching

Coach Kelly Sheffield’s volleyball team earned a berth at the national semifinals in Pittsburgh in December 2019, building on a record of excellence.

After the Badgers defeated top-ranked Baylor to advance to the NCAA title game, a jubilant Alvarez gave a brief, thunderous locker-room pep talk: “You made us all proud. And, man, did you COMPETE!”

Although the Badgers lost to Stanford in the title game, Alvarez greatly admires Sheffield’s coaching ability and drive for consistency. In 2013, Sheffield’s Badgers surprised the nation by advancing to the NCAA championship game, and Sheffield has been on a steady course since.

“That’s some real coaching,” Alvarez says. “That’s what it’s all about — developing kids and taking them to the highest level.”

Scoring a Hat Trick

In 2016, Alvarez was looking to hire a men’s hockey coach. He was intrigued by the idea of picking Tony Granato ’17, a former Badger and NHL star who was an assistant coach for the Detroit Red Wings.

“Every hockey guy I talked to said, ‘You can’t hire Tony. He’s an NHL guy,’ ” Alvarez says.

But he called Granato to ask about good candidates for the Badgers’ opening. Among others, Granato suggested his brother, Don ’93, along with Mark Osiecki ’94 — both former Badgers with strong résumés. Then Granato asked, “What about me?”

“He said, ‘If I come, I’m really close to Don and Oz,’ and those were the guys people were recommending,” Alvarez says. “We hit the trifecta when we hired Tony and got all three. That was exciting.”

Osiecki remains on Granato’s staff as associate head coach, while his brother moved on to the Chicago Blackhawks and Buffalo Sabres.

“Tony’s a guy who’s going to get it done,” Alvarez says of Granato’s quest to rebuild the program.

The Biggest Thrill

At the end of his career, Alvarez is also proud of the administrative team he’s built, including its response to the challenging landscape for college athletics brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For him, the deepest fulfillment came not from the scoreboards or the record books. It came from his teaching role.

“The thing that gives me the biggest thrill is when former players come back and say, ‘Coach, I still use the principles that I learned from you in how I raised my family or how I run my business. Some of the things you taught us echo in my mind, and you had so much influence.’

“I always answer, ‘This is why I was in the business. This means more to me than anything.’ ” •

Dennis Chaptman ’80 is a former sportswriter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel who covered the first decade of Barry Alvarez’s Wisconsin career. He’s also a former director of news and media relations for UW–Madison.

Published in the Summer 2021 issue

Comments

A November 29, 2022

Correction. Duke did not prove to be too much for the Badgers, the dirty refs did.