Say What Is True

UW creative writing professor Beth Nguyen tells bracingly honest stories about growing up Vietnamese American.

In the culinary world, umami is a savory taste that’s funky in a good way, a special something that lends depth to a food’s flavor. For many people, it brings to mind pho, a Vietnamese soup brimming with beef stock, rice noodles, sliced meats, and seasonings.

Umami is also integral to Beth Nguyen’s beef stroganoff recipe, the subject of her recent Bon Appétit essay, “I Thought Beef Stroganoff Was for Fancy People, Until I Made It My Own.”

“My secret ingredient is the same one every Vietnamese person has: a tiny bit of fish sauce, for depth and umami,” the award-winning author and UW–Madison English professor explains in the piece. Umami helps link the place of her birth (Saigon during the Vietnam War) to the place of her upbringing (the Midwest during the 1980s).

Despite its deliciousness, umami wasn’t recognized by the Western world for nearly a century after Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese chemistry professor, proposed the concept in 1908. American scientists insisted there were only four legitimate flavors: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. Meanwhile, families accustomed to hamburgers and TV dinners rarely discovered foods like pho, which were written off as unappealingly foreign.

Nguyen remembers how scents of Vietnamese cooking had her white friends heading for the hills during her childhood. The experience made her ponder her identity. As a Vietnamese refugee in a predominantly white part of Michigan, she was steeped in her elders’ way of life and shaped by their responses to their new environment. She watched as they rejected some aspects of the culture while embracing others, wondering what to reject and embrace herself. Plus, there were many mysteries to solve when visiting white people, from how to use a steak knife to who can sit at the head of the table.

Nguyen describes this predicament in her beef stroganoff essay: “I had to get used to friends calling my grandmother’s food weird, smelly, and gross. They’d run away from her stir-fries and pho, back home to the meatloaves and tuna casseroles we thought were weird, smelly, and gross. But their food was everywhere and ours hadn’t yet been mainstreamed or appropriated, so I spent a lot of time trying to figure out what American was supposed to mean.”

Throughout her quest to find the answer, Nguyen turned to books, especially those in the public library’s English literature section. With each page of Great Expectations and Jane Eyre, she read her way out of Grand Rapids. But what she read herself into wasn’t entirely satisfying. Later, in her own acclaimed books— two novels, a memoir, and an upcoming essay collection — she sought to understand why.

“I Can Relate” Moments

An epiphany arrived around age 14, when Nguyen realized she was too Asian for the Regency-era England of Pride and Prejudice — yet still drawn to it.

“I have nothing in common with the characters or [author] Jane Austen. It’s a foreign landscape for me, but somehow it’s relatable,” Nguyen says.

Finding something to relate to, however small, is a skill many minorities have honed because they’ve had to, she explains: “People of color are trained to read the literature of white people, and to read ourselves into it. Only recently have white people started reading themselves into literature that’s not about them.”

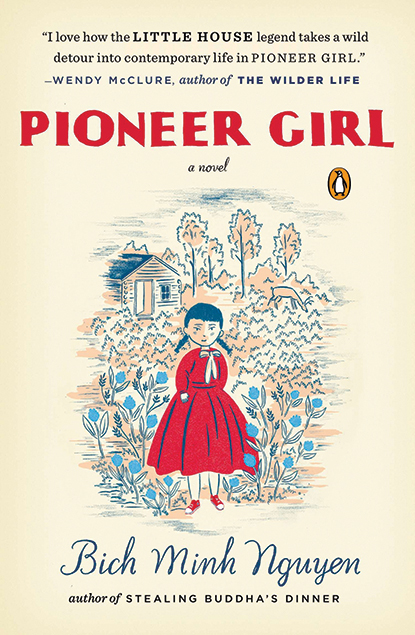

Nguyen’s two novels are fine examples of that progress. Short Girls, winner of a 2010 American Book Award, follows two Vietnamese American sisters as they struggle to connect with each other and come to terms with themselves. Her 2014 novel, Pioneer Girl, features a Vietnamese American’s attempt to prove that her family’s history is intertwined with that of Laura Ingalls Wilder, author of Little House on the Prairie. A white reader is likely to feel foreign in this milieu, encouraging empathy and perspective-taking. Those tiny “I can relate” moments can help people who couldn’t be more different build common ground. Plus, feeling like an outsider is uncomfortable — something majority populations don’t often encounter in everyday life.

As a white person, I feel anxiety and shame while reading about the racism Nguyen experienced. I witnessed some of the situations she describes in my own 1980s childhood, and I’m not sure how I responded. I’m better at identifying racism today, and I’m dedicated to fighting it, but I still struggle. Sometimes I respond at the wrong time. Sometimes I use the wrong words. Sometimes I’m too focused on myself. It can get messy, but I keep trying, and reading helps.

Though these feelings hurt, they’re tolerable thanks to Nguyen’s skillful storytelling. Her prose is laced with rewards for the reader, including humor and ’80s pop-culture references. Like umami, it’s both powerful and delectable.

Blending in (or Not)

Though umami is found in some of white America’s favorite foods — tomatoes and parmesan cheese, to name two — it’s often dubbed exotic, perhaps because an Asian person pioneered the idea. For instance, on its website, Real Simple notes that umami is “funny-sounding.” Translation: it must sound amusingly foreign to native English speakers.

For Nguyen, comments like this can feel personal. “Funny-sounding” is one of the more benign remarks people have made about her legal name, Bich Minh Nguyen. In her New Yorker essay “America Ruined My Name for Me,” she explains that “a name like Bich (pronounced ‘Bic’) didn’t just make me stand out — it made me miserably visible.”

Nguyen is pleased to see a wider range of voices than ever before in the publishing world.

As a child, the more Nguyen tried to blend in, the more she seemed to stand out. She noticed differences everywhere. How other families worshipped tidiness — and an unfamiliar god she was supposed to know personally. How they expected her to have “good manners” her own family hadn’t taught her. How her classmates broadcast their status through their lunches, upstaging her squashed sandwiches with thermoses of SpaghettiOs. She worried about being weird, smelly, and gross — and if others told her she was, she accepted it.

“For a long time, I went along with what other people told me to do, whether they were white or Asian,” Nguyen explains. “I felt I didn’t even have the agency or power to decide what my name is. It took me three decades and ethnic studies classes to figure that out, and to give myself permission to go by a different name.”

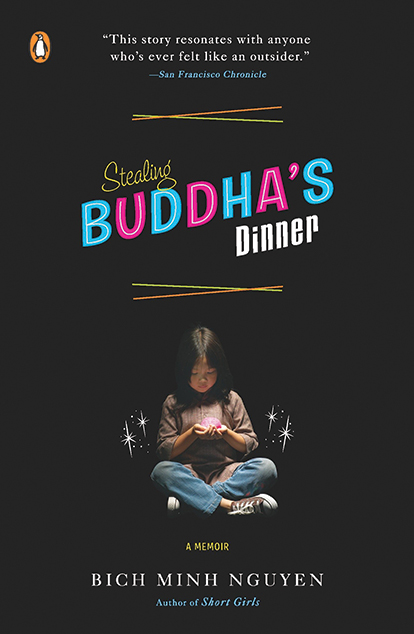

Nguyen also had to grant herself permission to write 2007’s Stealing Buddha’s Dinner as a memoir. She trained in fiction and poetry in the University of Michigan’s MFA program, so she assumed it was fiction when she began it. Over time, the tale felt too true for that approach.

“I realized I wasn’t using fiction for its imaginative process but for a disguise. I had to give myself permission to write the real story,” she says.

Nguyen had to be willing to stand out, and stand out she did, winning a PEN/Jerard Fund Award. Since then, Stealing Buddha’s Dinner has appeared on reading lists for high school English classes and college ethnic studies courses, the kind that helped Nguyen find words for many of her childhood experiences. The book also helped her land teaching positions at Purdue, the University of San Francisco, and most recently UW–Madison, where she and husband Porter Shreve joined the creative writing faculty in 2019.

According to Jeehyun Lim, an Asian American literature expert at the State University of New York at Buffalo, Nguyen is a master of balancing the general and the specific.

“The way she recognizes huge questions makes her writing really good,” Lim says. “But everything is anchored in individual circumstances, which prevents generalized proclamations and creates memorable moments for the reader.”

Unsurprisingly, some of the most memorable moments in Nguyen’s work are her own memories of food.

Into the Unknown

In Stealing Buddha’s Dinner, Nguyen uses food as a marker of her childhood trials and tribulations. Each chapter is named after a food or food-centric activity, inviting readers to connect some of their own memories of eating to the story being told.

“A memoir is an attempt to understand something rather than just chronicle it, so Stealing Buddha’s Dinner needed a different kind of form, something that wasn’t chronological. That’s why I chose chapter headings like ‘Pringles,’ ” she says. “One of my earliest food memories is of eating Pringles. I feel this strange amazement when I think about the metaphorical weight of something so processed, so packaged, so American.”

Pringles help Nguyen describe her family’s journey from Vietnam to a refugee camp in Arkansas to the strange surroundings of western Michigan. Similarly, umami-rich salt pork represents her efforts to identify with Caucasian literary heroines, especially those from Wilder’s Little House series. As Nguyen puts it, “I thought that if I could know inside and out how my heroines lived and what they ate and what they loved … [then] I could be them, too.”

Instead of trying to be Laura or Rose from Little House, Nguyen gives these characters a new story in Pioneer Girl. But the tale primarily belongs to Lee Lien, a Little House fan struggling to find work after completing her dissertation. She moves back home, subjecting herself to her mother’s constant criticism and soul-crushing work at her family’s restaurant.

Lee shares many qualities with Nguyen: she’s from a Vietnamese refugee family that settled in the Midwest, her household is multigenerational, and she looks to a beloved grandparent for comfort. Lee lost her father to drowning while Nguyen’s disappeared when her family migrated, a topic she’ll explore in her forthcoming essay collection, Owner of a Lonely Heart.

One day, Lee and her brother find a brooch that bears an uncanny resemblance to a pin described in Wilder’s novel These Happy Golden Years. Before long, Lee embarks on a quest to determine if Wilder’s daughter, journalist Rose Wilder Lane, befriended her grandfather in Saigon years ago.

Lee isn’t plowing fields or building log cabins, but she realizes she is blazing a trail of her own. She persists despite difficult conditions, including pressure to help run her family’s café. Though historians like Frederick Jackson Turner 1884, MA1888 declared the frontier gone by the 1890s, modern immigrants are pioneers in many respects, daring to venture into the unknown. Hardships are a rite of passage, and over time, immigrants can call the place they’ve settled their own.

This analogy is far from perfect, and so were pioneers. Many killed Native Americans or forced them to give up their sacred lands. Racism tarnishes the Little House books — and many readers’ fond memories of them. In Pioneer Girl, Lee must come to terms with these facts and distance herself from the Wilder women she’d admired for so long.

“Lee realizes that she is not the same as Laura or Rose, because if she transported herself back in time, she’d be closer to the position of a Native American,” says the critic Lim. “This novel generates a lot of food for thought when it comes to the history of settler colonialism and where Asian Americans fit into that history.”

Nguyen says she felt deeply disturbed when rereading the Little House books as an adult.

“Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books were deliberately given to immigrants as an introduction to American life and ideals, so I grew up reading them without context or explanation. When I read them again as an adult, I saw how problematic they are in terms of race and the treatment of indigenous peoples. These books were legends, and they had a great deal of influence for decades.”

“I want to hear stories from people who are honest about their mistakes and the ways their minds are evolving.”

Thankfully, attitudes are shifting. If pioneering includes violence and racism, then it shouldn’t be a goal for immigrants or anyone else. But what should?

Warts-and-All Storytelling

Honesty, says Nguyen. Vulnerable, warts-and-all storytelling from as many voices as possible.

“I want to hear stories from people who are honest about their mistakes and the ways their minds are evolving. I want them to say what is true to them, not what other people tell them they should say,” she explains.

Nguyen is pleased to see a wider range of voices than ever before in the publishing world. She says this empowers readers to tell their own stories and reminds them that they should, not only for themselves but for others.

“Every time we read about something unfamiliar to us, that writing becomes a door or a window,” she says. “It leads us to the next place.”

And if we’re lucky, that place might have a bowl of pho in the kitchen. •

Jessica Steinhoff ’01 is a journalist, cultural critic, and therapist in training. She’s working on a novel herself.

Published in the Winter 2021 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.