Madison Calling

Can you hear me now? Kate Koberle, a floor manager for the UW Foundation’s Telefund program, gets an earful from Abe. Photo: Bryce Richter

Hoping to double alumni donations, the UW prepares to roll out an aggressive campaign. The key lies in getting to know you.

Why do so many of you fear Kate Koberle x’13?

She’s not a bad person. Underneath her Zooey Deschanel bangs are a sunny disposition and serious work ethic that make her the sort of daughter any UW alum would wish for. She studies landscape architecture. She aspires to run a marathon. And she’s doing her best to pay her way through school — or at least as much as anyone can in these days of $5,000-per-semester in-state tuition.

“My parents are paying for my room and board, which is great,” she says, “and they’re paying for all my food. But I’m paying for my tuition and my textbooks.”

That’s where the fear comes in — or if not fear, at least avoidance. Koberle works part-time for the University of Wisconsin Foundation (UWF), where she’s a floor manager for Telefund, the program that employs about a hundred students to call alumni — and parents of current students, and others — to solicit donations to support the university. For many grads, Telefund is all they know of UWF: a voice at the other end of a telephone line, asking for money. But last year, better than nine out of every ten of you tried not to have any contact with Koberle and her colleagues, or anyone else from the foundation.

That’s a matter of concern for the university. Telefund is one of the main sources of revenue for the annual fund, which is the pool of money that the foundation gives to UW-Madison each year to spend on whatever the university sees as its areas of greatest immediate importance: need-based scholarships, building maintenance, library improvements — the sorts of things the UW absolutely has to take care of, but that big donors seldom consider very sexy.

Last year nearly 38,000 UW alumni donated to the university’s educational mission — that is, leaving aside gifts to the athletic department. They contributed some $4 million, about half of which came through Telefund. To Mike Knetter, UWF’s president and CEO, those numbers are far too small.

When Knetter took over leadership of the Foundation in 2010, he found an organization with some $2.6 billion in assets. But that’s not cash. Most of it is in the UWF’s endowment, meaning that it’s intended to exist as a permanent investment. Binding contracts specify that the university can receive only a small amount, typically less than 8 percent, in any given year. Further, the vast majority of those assets — more than 93 percent — are restricted, meaning that the university can spend those dollars only for specific purposes designated by the donors, regardless of what campus might want or need.

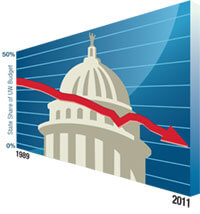

Once upon a time, this worked out well. The university could depend on the state to pay its core expenses, while donations from alumni acted as what Knetter calls a “margin of excellence” — the additional dollars that would elevate basic education and research to world-class status. But state support has dropped from 35.3 percent of the UW’s budget in 1989 to 26 percent in 1999 to 17.6 percent in 2011.

“The traditional thing,” says Knetter, “is for state and tuition dollars to pay for the core budget, and [we’d say] that philanthropy … is the icing on the cake. But now it’s got to be part of the cake, as well, if we’re going to maintain the university in the way that we’ve come to expect it.”

Knetter believes the future of the university is tied to the health of the annual fund. This fall, UW-Madison is launching a campaign to double that fund’s donations, both in dollars and in the number of alumni who make gifts. To make this campaign work, however, the UW will have to understand why it is that so many of you avoid Kate Koberle.

The State of the UW

If you haven’t yet heard about UW–Madison’s new annual fund campaign, you will — and you’ll hear about it a lot.

Called Share the Wonderful, it will be a saturation effort. From now until November, you’ll see ads on television, online, in your mailbox, and in publications (including On Wisconsin). The effort is necessary, because the UW’s goals are aggressive:

- To receive gifts or pledges from between 40,000 and 60,000 alumni.

- To bring in $8 million to the annual funds of UW–Madison and its various constituent schools, colleges, and departments.

- To add a further $3 million to need-based aid programs for students.

The campaign will require UW- Madison to change its fundraising culture. In the past, it has focused on courting wealthy alumni to give large gifts aimed at specific purposes — restricted gifts, in the language of philanthropy. Knetter is stressing to UWF staff that they have to encourage unrestricted gifts, even if they’re smaller, and be prepared to justify what unrestricted dollars can do.

“I’ll meet donors occasionally [and] talk about the importance of less-restricted gifts,” he says, “and they’ll say, ‘Well, you know, I tried to make an unrestricted gift one time, and your staff got me to restrict it.’ In a way, it’s easier to steward a very restricted gift, because you can report out on exactly what that gift did.”

A switch to emphasizing unrestricted gifts will enable the university to think more strategically about how it spends money. But it will also require the university to think more strategically about how it raises money — another cultural shift.

Rather than sending out a large number of solicitations throughout the year, “this campaign will run like the United Way, perhaps just for two months,” says UW interim chancellor David Ward MS’62, PhD’63. “Everybody else would agree not to solicit during that period, so that you would have two months in which the solicitation would be unambiguously focused on large-scale, university-wide fundraising.”

That will mean that all the various campus entities — UWF, schools and colleges, the alumni association, the Union — will have to set aside their own mailings and their independent goals and let the annual fund take center stage.

“We’ll have to work in concert more than ever,” says Paula Bonner MS’78, president and CEO of the Wisconsin Alumni Association. “We’ve come to a point where we can’t focus so much on this individual project or that individual department. We’ve got to get the whole campus community to speak with a single voice, to tell our grads what it will take to keep the UW a world-class university.”

It’s a change that Knetter believes is overdue.

“We’ve been telling the story so long that philanthropy is the margin of excellence, that it’s the state’s job to [pay basic costs],” he says. “It was a nice way to sell philanthropy in those early days. Unfortunately, those days changed.”

Slipping State Support

In recent decades, state tax dollars have steadily become a smaller share of UW–Madison’s budget, dropping from 35.4 percent in 1989 to 17.6 percent in 2011. Only 10.3 percent of UW–Madison’s budget in 2011 came from general-purpose — that is, unrestricted — state funds.

The State of the State

The state isn’t likely to return to the early days and pay a higher share of the UW’s budget. It has too many other obligations, and there remains a disconnect between what the UW is doing and how citizens view the UW. To understand why the legislature doesn’t make funding the university a higher priority, one only need listen to voters. And no one has listened more closely to Wisconsin voters than Kathy Cramer Walsh ’94.

A UW professor of political science, Walsh has spent the last several years conducting research by sitting in on conversations in coffee shops, diners, and gas stations around the state, to understand how people talk about different political issues.

“There are certain places in every community where people get together to shoot the breeze,” she says. “And everybody knows that if you want the local news, that’s where you go to get it.”

These conversations have provided material for several research articles, including a working paper posted online in spring, for which Walsh asked her local pundits what they thought of UW–Madison. What she found was that outside of Madison and Milwaukee — in “outstate” Wisconsin — some people feel an emotional, political, and economic distance from the university. While they consider it an excellent educational and research institution, they think that it’s inattentive to the concerns of those who live outside of Dane County.

But the sense of distance, she believes, springs from Wisconsinites’ affection for their state university. “Especially with respect to the University of Wisconsin-Madison,” she says, “there’s a very profound fondness toward this place. It’s as though they feel so positive about it and feel as though it is their institution, that they want people on campus to listen more to their concerns. Because they care about it, they have strong feelings about it.”

Among those feelings was that the UW receives more than enough public funding already — and that it doesn’t do enough to give the state a return on its investment.

“It’s not surprising in many ways,” Walsh says. “This is a very privileged institution, just in general, [as well as] in comparison to the lives that many people in Wisconsin live. When you’re part of a place like that, you’re often blind to the people beyond it and blind to the ways in which [they] expect a lot of you because you are privileged.”

The university isn’t simply holding out its hand, waiting for new funds to fall its way. To achieve what the university envisions for the future, the campus is spending time looking seriously at its own operations and working from within to identify solutions to its funding challenges.

“Securing our position in the world for the future will not happen by doing things the way they have always been done,” Ward says. “We have to do things differently, because there’s no way we can continue on the same path. Too much is changing around us, so we must change ourselves.”

A trio of campuswide efforts is driving the university to become more nimble and creative, while at the same time strengthening its status as a leading research institution and educational innovation incubator.

An effort aimed at enhancing student learning will also improve the university’s capacity and identify new revenue sources. Ward is encouraging the academic community to explore how best to leverage online technology in instruction, which will lead to more courses being delivered by a blend of remote and face-to-face delivery — what’s called “blended learning.”

“Elements of courses will be conducted over the Internet, but a student’s experience will still be anchored in this physical place, which we know is so very important to our students,” Ward says. “We can diversify the timing, flexibility, and format of the learning experiences we offer by using technology wisely, and we are exploring new configurations of disciplines, departments, and curricula in response to changes in the discovery and integration of new knowledge.”

This effort, along with a second one aimed at achieving administrative excellence by enhancing efficiency, effectiveness, and flexibility, are approaches to help bridge the growing revenue gap.

A third initiative, called HR Design, is intended to give UW–Madison the tools to attract, develop, and retain the exceptional and diverse talent it needs to maintain its reputation.

“All three efforts leverage our culture of collaboration, innovation, and responsibility, and are helping us develop a comprehensive approach to best using our resources,” Ward says. “By preserving and enhancing the university’s reputation, we can define our own vision for higher education in a new era of greater self-sufficiency.”

And yet there remains a difference of opinion between the university and the state over the level of tax support UW–Madison deserves, a difference that has only grown with economic changes during the last few decades.

“Financially, the sixties and seventies were a pretty good period for the state of Wisconsin, because it was a pretty good period for manufacturing and agriculture as competitive strengths for the American economy,” Knetter says. “That really started to shift with globalization and then the information technology revolution. Growth has shifted much more to the coasts and the Sunbelt, [and] the tax base, particularly in states in the upper Midwest, has just been beaten up. That’s created some major problems for public universities, because the tax base for funding our traditional mission just isn’t going to be there.”

Slow growth in the state’s tax base means that the university must increasingly rely on voluntary gifts from those who’ve received the most direct benefit from the UW: its graduates.

“Shame on us if we ever denigrate the investment that the state and taxpayers have made,” Knetter says. “That would be ridiculous, because they’ve built a university that’s way out of proportion to the resources of the state, by anyone’s accounting. And now, if we [alumni] are not willing to sustain it, that’s our problem.”

The State of Alumni

Nobody knows how to talk to UW-Madison alumni like Kate Koberle and her colleagues do.

Six nights a week, the Telefund room at the UWF building buzzes with activity. From 5:30 to 9:00, as many as forty students sit in rows at computer screens, working the phones, while three managers walk the floor, offering advice and encouragement.

“The role as a floor manager is to monitor phone calls and see how [callers] are doing and provide feedback,” Koberle says. “You want to make sure that they are going through their calls as they should be and not giving up.”

To go through the call means that students have to follow “the ladder,” the amount of money that the foundation hopes each call will generate. It’s called the ladder because it starts high and works downward, step by step, until the caller finds a figure that the prospective donor agrees to.

“In every call, you absolutely have to stick to the ladder,” Koberle says.

But the floor managers also give tips on how to talk to alumni, the basic lore that’s passed down across the generations of Telefund students: be real, be relatable, be positive.

“I talk [with alumni] about their experiences on campus and how maybe things have changed, but also about things that we have in common,” she says. “I ask how well they got to know their professors or if they had any favorite classes and stuff like that, and sometimes I actually find overlap in classes that I’m taking now. [You want them to] know they’re not just talking to their standard telemarketer, but they’re actually talking to a real person who’s actually studying at the University of Wisconsin.”

When calling alumni who’ve donated before, they can expect big returns — often a pledge rate of 80 percent or better. But when talking to alumni who haven’t previously donated, the level of success drops off significantly. “I think it’s typically a 5 to 8 percent pledge rate,” she says. And that’s among just the few dozen alumni they speak with during a night when they may dial hundreds of numbers.

It’s this resistance that Knetter wants to change. He first came to Madison as the dean of the School of Business, after graduating from Stanford and serving on the faculty at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business. He found himself surprised by the UW’s philanthropic record, both with its successes and its shortcomings.

“The Tuck School of Business is a pretty good fundraising machine, actually, even among business schools,” he says. “I think [the Wisconsin School of Business’s] endowment value was at about 70 percent of what the Tuck School’s endowment was, which I was pretty impressed by. But then our annual giving was only about 14 percent [of Tuck’s]. So clearly we’d done well in getting these endowment gifts, but not very well in developing a tradition of annual giving.”

A similar split applies to the university as a whole. In 2005, UWF had the forty-ninth largest endowment among American universities. By 2011, it had risen to thirty-fourth. But unrestricted annual giving has been stagnant.

“Some universities have very strong loyalty giving, and they’re trying to get to where we are in terms of their major giving piece,” says Alisa Robertson ’94, MBA’03, Knetter’s chief of staff and marketing. She defines major giving as those headline-setting, million-dollar bequests — typically once-in-a-lifetime gifts that go for a very specific purpose: Herb Kohl ’56 offering $25 million for the Kohl Center, or Jerome ’48 and Simona Chazen donating $25 million for the UW’s Chazen Museum of Art. Loyalty giving, however, refers to the donations a person makes to an organization every year — smaller gifts, generally, but with few restrictions.

“We have been able to build a major-gift operation without having that loyalty piece, which is a little weird, because you’d think you’d have to have loyalty to get to that other piece,” Robertson says.

To illustrate the difficulty in establishing loyalty giving, note that some 65,000 grads have never given a cent to the UW. To try to find out why so many alumni are reluctant to give, and how best to convince them to change their minds, the foundation commissioned a study by the A.C. Nielsen Center for Marketing Research at the School of Business. The center’s director, Professor Neeraj Arora MS’98, PhD’00, gave the project as an assignment to four of his students from the MBA class of 2013: Matt Johnson, Valerie Kuts, Kevin Sisco, and Cally Thornton.

The group had callers from Telefund survey nearly a thousand alumni who’ve never donated, seeking to learn why graduates choose not to give to the UW and what might change their minds. The survey presented a series of statements and asked how persuasive they would be in opening the respondents’ checkbooks:

- “When you donate to the UW, you can choose the school, department, or program that receives your money.”

- “Support from alumni like you allows faculty to conduct research that has an impact on the world.”

- “State funding per student at UW–Madison has dropped by 9.3 percent in the past decade.”

- “Your gift of $11 buys a required textbook for a student in need.”

The Nielsen students used demographic data to divide the alumni into a variety of segments. But to their surprise, they found that responses tracked in a similar way across all the groups. Irrespective of age, sex, region, or financial status, most alumni feel proud of their connection with the UW. They’d be more inclined to give to the university if they felt that it would enhance its reputation and strength. They’d like to see their gifts go to help the programs they choose, and to make new discoveries, particularly in medicine.

Conversely, they’re less sympathetic to arguments based on repairing a shortfall due to state budget cuts. They aren’t impressed that alumni from other eras donate more than they do, or that alumni from other universities give at a higher rate than Badgers do.

“We thought that there would be much bigger differences in how people responded to the messaging,” says Thornton. “We had tested thirteen different messages, and what was very surprising to us was that the ranking of the messages came out very consistently the same. No matter how we broke it down, [alumni] responded to the messaging in the exact similar way.”

Stating the Case

For UW–Madison, this is mixed news. On the one hand, it means that a campaign that reaches out to alumni doesn’t need to have an elaborate marketing strategy. If alumni across all regions, ages, and economic strata react the same way to messages about the UW, then there’s little need to break down the alumni population into segments and go after it piecemeal.

But the other side of the argument is this: if there’s not a striking insight into how to inspire alumni to give, then how will the foundation manage the dramatic increase that Knetter believes is necessary?

And his goals are aggressive. The $11 million total for this year is just the first stage in a journey toward hitting $20 million annually by 2016. The foundation will aim for these goals in spite of a sluggish national economy — and partially because of it. The recession that hit in 2008 damaged the university’s bank account — UWF’s total assets under management have yet to return to the nearly $2.9 billion it had five years ago. But college graduates have managed to ride out the recession better than those without degrees.

“We have to educate our alumni to think about contributing more than just that margin of excellence,” Knetter says. “And frankly, we think that the benefits that they derive from their experience here are worth that. It’s on us to make the case that that’s the day we’ve come to.”

But communicating will mean more than just telling alumni what the UW wants and needs. It will also require telling alumni what the UW is doing with those donations.

“We need to show greater clarity on the part of the university about its strategic objectives, and the role we need philanthropy to play in achieving them,” Knetter says.

If the UW gets better at communicating with alumni about its financial health, it may be able to better communicate with all of its stakeholders — the members of the state government, businesses, and the citizens of Wisconsin. And if the university is successful, it will make Kate Koberle seem less scary to you, which, really, is all she wants out of her work.

“It’s very, very fulfilling,” she says, “getting to work with alumni and do good things for the UW. I feel like I’m really doing good.”

John Allen is senior editor for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Fall 2012 issue

Comments

Fiona Mackenzie September 23, 2012

I am SO not thrilled that my university (for 5 generations) is subsidizing Koch industries and ALEC with the state money to which it is entitled, and then coming to me for money to make it up. “We” chased away Joe McCarthy and were a loud voice against the Vietnam war and racial inequality. What happened?

Michael G November 12, 2012

I’ve been thinking about this for a couple of months since I received the latest issue of On Wisconsin. I received a phone call from one of the student workers last night. It seems that Knetter and others just really do not get it. I know a number of other alumni similar to myself who are just variations on the same theme. The lead-in to the article says “The key is getting to know you”. Well, when I was a student at UW I was pretty much just a number. Once you graduate and they want your money all of a sudden they want to get to know you. Undergrads are generally pretty little affected by the ‘research’ that many of the faculty are doing on campus. If donating to UW were to enhance instruction where many of the undergrads had to suffer through TAs who literally cannot tell the difference between “duck” and “dog” you might be more successful. In this day and age of layoffs and underemployment I have yet to see UW talk about any changes to they way that business is done on campus. Still the same sabbaticals (that nobody else in the world gets) to do suspect research that, as I noted, little affects undergrads. I was recently on campus and stopped by University Bookstore. $260 books for one semester? Talk of tearing down Humanities because it does not fit the vision for that part of campus? It would appear that no effort whatsoever is spent on cost control. Just have the students borrow more money and then, with tens of thousands in debt, UW calls them up and asks for more money?