In Memory of Lou

Alzheimer’s disease looms for America’s black and Hispanic families.

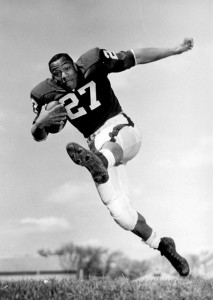

Lou Holland ’65 was a UW–Madison success story. A Badger Hall of Fame halfback who traded his jersey for a business suit after graduation, he went on to stardom in a new arena as an investment professional. Holland created a successful institutional management firm and became a regular guest on the PBS program Wall Street Week.

But there was ultimately one challenge Holland could not overcome: Alzheimer’s disease. He passed away in February.

50% of people with Alzheimer’s disease are not diagnosed.

“My dad was competitive,” says his son Lou Holland, Jr. ’86, himself a former tailback who lettered for the Badgers. “He wanted to win, but right now there is no way to fight or cure Alzheimer’s disease.”

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease can also be both difficult and emotionally painful for family members. “It’s the little things that you don’t want to see,” says Holland. “You want to say it’s stress or he didn’t get enough sleep and deny what you are seeing. But things start to add up. My old college roommate who he’d known for years saw him on a plane, and Pop didn’t remember him. There were times when he couldn’t find his way back from someplace.”

When his father’s reading skills started to fail, Holland couldn’t deny the signs any longer. “My dad would read countless papers very quickly every weekend,” he says. “Then he started cutting out of family events earlier and earlier to take his papers upstairs to read. That just was not him. That’s when we knew we had to step in.”

As the U.S. population ages, Alzheimer’s has become the sixth leading cause of death. And research shows that people who have relatives with the disease are at a higher risk of developing it themselves. Holland’s grandmother and aunt also died of complications associated with the illness.

“I’m going on fifty-two,” Holland says. “It’s already in my system, if I am going to get it. This disease takes a foothold before it can be diagnosed. It may be too late for me. I’ve made my peace with that, but I have three kids. I want this thing to be stopped or slowed down in my generation.”

Holland is helping to accomplish this by participating as a research subject in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention study, or WRAP. As an African American, Holland’s participation is critical. In the United States, Alzheimer’s is twice as common among blacks as it is among whites, and one and a half times as common among Hispanics. It is often diagnosed at later stages among these groups, and later diagnosis limits the effectiveness of treatments that depend on early intervention. Some 50 percent of people who have been diagnosed with the disease are not treated appropriately, and this figure may be higher in minority communities.

Recognizing the approaching health crisis that Alzheimer’s disease will impose on communities of color, the UW Alzheimer’s Institute, with the support of Bader Philanthropies and the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, has developed a statewide outreach program centered in Milwaukee to recruit African Americans for WRAP. Milwaukee County is home to more than 240,000 African Americans, nearly 70 percent of Wisconsin’s African American population.

WRAP, a long-term study of adult children of people with Alzheimer’s disease that launched in 2001, stands out as the largest and longest-lived study of its kind in the nation. Its focus is to determine who is at risk for Alzheimer’s. Researchers are compiling a wide range of information on more than 1,500 participants, assessing their background, medical history, and lifestyle, including exercise and diet. The study also collects vital signs, conducts brain imaging, and tests cerebral spinal fluid, searching for biomarkers that may be present long before the disease expresses itself. Researchers also collect blood samples to look for genetic risk factors.

“When I saw what we had at the university, it made perfect sense for [my family] to get involved,” says Holland, whose older sister, Jeanette, is also participating in the study. “I’ve been poked and prodded through my second or third round of testing so far.”

Holland, who is also a national board member of the Alzheimer’s Association, is so invested in finding a cure that he and his family have endowed the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute Holland Research Fund. But he is also commited to removing the embarrassment that Alzheimer’s patients and their families feel.

“I know there is a stigma about being in public with a person who is hanging on your arm, and you can’t turn your back from them, or they are drooling down their chin, but every Alzheimer’s patient has a story,” he says. In the early stages of the disease, he adds, patients know what’s happening, and they feel the stigma their condition can carry. “We need to get past that,” Holland continues. “There are prominent people today, from entertainment to sports to Fortune 500 companies, dealing with Alzheimer’s, and I wish their families would speak up.”

6th Alzheimer’s disease is the 6th leading cause of death in this country.

• • •

By definition, a long-term study of people who are at risk requires waiting years until symptoms appear. But the UW study is beginning to identify cognitive changes that may be early signs of Alzheimer’s disease, and researchers hope this will provide the groundwork for early diagnosis and possible treatment. One example: last year JAMA Neurology published early findings that give scientists a better understanding of how insulin resistance or pre- diabetes changes the way the brain uses sugar, and suggests a possible link between high blood sugar and Alzheimer’s.

Within twenty-four hours of announcing the study on television, WRAP had almost six hundred volunteers. But unfortunately, they did not initially include a representative number of people of color — a problem that plagues Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials around the country, according to Consuelo Wilkins, the executive director of the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance, a partnership between Meharry Medical College and Vanderbilt University Medical Center that develops initiatives to integrate biomedical research and community engagement. “Nationally, less than 5 percent of participants in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials are nonwhite,” she told an audience during a recent campus visit.

Speaking later to a community group on Madison’s south side, Wilkins said that as the American population is graying, members of minority groups, who previously had lower life expectancies, are also living longer. “For some of us who might not have seen Alzheimer’s disease in our families, we are going to start to see it,” she says. “Eventually, today’s minorities are going to be the majority. Are we going to have the treatments and strategies in place to address this?”

Fabu Carter MA’86, MA’81, outreach specialist for the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, attributes the difficulty in recruiting African American volunteers partly to instances of abuse in clinical studies in the past. “Most people are very aware of the Tuskegee experiments and of Henrietta Lacks’s treatment,” she says.

Lou Holland, Sr., was a Badger Hall of Fame halfback who led the Big Ten in scoring in 1962 and 1963. Wisconsin Athletics

The infamous Tuskegee University study, conducted from 1932 to 1972 in conjunction with the U.S. Public Health Service, observed the progression of untreated syphilis using six hundred rural African American men as subjects. None of the men were told they had the disease or treated with penicillin, even after the antibiotic became the standard treatment for syphilis.

Henrietta Lacks, an African American woman who was treated with radiation for a tumor, had two samples of her cervix removed without her permission. These cells were ultimately commercialized into the valuable HeLa immortal cell line without informing or compensating her family. Scientists have grown twenty tons of tissue from her cell line, and they have generated almost eleven thousand patents.

Carter cites other barriers to participation. Lower-income Milwaukee residents may have less access to health care in general. And, because African American culture has a tradition of revering its elders, she says, it can be difficult for family members to admit that their loved ones are losing their faculties.

But staff in the Milwaukee Outreach Program have made significant inroads. Gina Green-Harris, director of the program, calls WRAP a microcosm of the Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute. Since 2008, the number of African Americans enrolled in the study increased from seven to 158. Researchers want to include up to 500 within the next five years.

The Milwaukee outreach effort includes the Chorus Project, a choir led by professional musicians and made up of both Alzheimer’s patients and their caregivers. The chorus provides both a support network and an environment that stimulates social engagement. The participants suggest songs that remind them of good experiences, such as singing in church or falling in love. The singers rehearse for thirteen weeks before presenting a concert to family and community that works to raise public awareness and help reduce the stigma associated with memory loss.

8 The number of years patients live, on average, after their symptoms become noticeable.

Other programs include Breaking the Silence, a community dialogue started two years ago to address Alzheimer’s and communities of color. “We identify well-known people from across the country who have dealt with Alzheimer’s disease directly to come and talk,” says Green-Harris. The first event drew 250 people, and one held last year in Milwaukee and Racine attracted more than 500. “It tells us that people want to hear more about this,” she says.

Unique to the Milwaukee program is an outreach specialist who goes into people’s homes and helps them get started with the diagnostic clinic. “We do not charge for this,” says Green-Harris. “That helps build credibility with providers and helps families accept the diagnosis. Then as they transition to care services, we have a support person to undergird them.”

That support person is outreach specialist Stephanie Houston, who enables the program to stay connected with the families who participate in the study.

“We knew we could not just come into the community and say ‘You should participate in research,’ ” says Houston. “First we listened to what the community was saying.” To accomplish this, Houston developed an advisory board made up of legal experts, social workers, caregivers, and professionals from local organizations.

The board learned that what the community wanted was information. The Wisconsin Alzheimer’s Institute now hosts workshops on requested topics such as finances, dealing with challenging behaviors, and establishing power of attorney. “We also hold workshops within our faith communities,” says Green-Harris. “The church is a valuable social network that helps us let people know what is happening with aging.”

This outreach to people in their churches and community support groups is crucial, says Houston. “We have to reach them where they are. … Our goal is to be a community resource as well as responsible researchers because at the end of the day, we know we are going to be accountable, and we see the need.”

Meanwhile, Holland will continue the fight. Watching his father struggle has given him a keen appreciation of the ravages of Alzheimer’s. “The cost is immeasurable to your being as you watch your parent become a child. When you have to help him go to the bathroom, the effort is emotional. It challenges your faith and your family. … It pulls on your heart,” he says. “Research is playing catch-up with a disease that is an Olympic gold-medal champion. Alzheimer’s has never lost. We are behind for now, but we are gaining on it.”

Denise Thornton is a freelance writer based in Wisconsin’s Driftless area.

Published in the Summer 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.