For the Love of Vanilla

UW botanist Ken Cameron studies the flowers that produce the world's favorite flavor. Can he save them from extinction?

Think about the products you’ve used since you woke up this morning: the toothpaste on your toothbrush; the yogurt with your breakfast; the fragrance on your dresser; the pills in your medicine cabinet. The taste that lingers on your tongue long after you’ve rinsed and spit and the note that scents your skin well into your workday is none other than that old sensory refrain: vanilla.

A signature flavor that’s easily overlooked but that would be sorely missed, vanilla is the steady hum of the olfactory and gustatory worlds, a base note that serves as the foundation for many beloved sensations and that flourishes on its own.

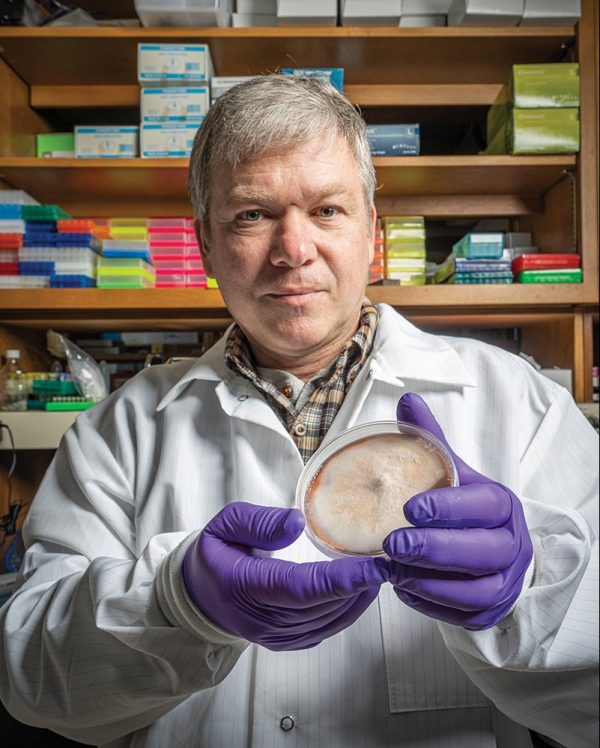

“It’s literally the most popular flavor and fragrance in the world, and it’s a multimillion-dollar industry,” says Ken Cameron, a professor in the UW Department of Botany and director of the Wisconsin State Herbarium.

Vanilla may be popular, but it’s also misunderstood. Though it’s in a multitude of products, people don’t always recognize it when they smell or taste it. Even less well-known than vanilla’s prevalence is its origin. While vanilla “beans” are its most recognized source, these beans are actually the pods, or fruit, of orchids. Not only that, but the Vanilla orchids trace their roots back to land on which even dinosaurs had yet to roam. (Vanilla — in roman letters, lowercase v — is a flavor and a fragrance; Vanilla, in italics, capital V, is a genus of about 110 species of flowers.)

Despite its ubiquity and rich history, vanilla still bears the reputation of blandness — of being plain. Plain, however, is not the presence of vanilla, but a world without it: as environmental conditions become more threatening to a plant that’s survived mass extinctions, the possibility of a blander future — or at least a more artificial one — becomes ever more likely.

As the world’s leading expert on Vanilla orchids, Cameron intends to save what parts of this species he can with the help of fellow scientists seeking to reinforce its chances of survival and restore this now-fragile plant to its former glory.

Anything but Plain

“I think a psychologist should do a study,” Cameron says. “Hook up human brains, and then show them pictures of flowers. I bet that when they see an orchid flower, some interspecies, human-connection, neuron pathway lights up.”

It’s not his affinity for orchids that inspires Cameron’s hypothesis: the leading theories about humans’ passion for them really do carry romantic undertones.

“Some people think it’s simply the romance of the tropics and this desire to possess something that seems rare and elusive and from another continent — although they do grow right in our own backyards, so that doesn’t hold up entirely,” Cameron says. More probable, he suggests, is that our infatuation with orchids actually reflects an infatuation with ourselves.

“The orchid flower is really different from so many other flowers because it has what we call bilateral symmetry: the left side and the right side are equal, mirror images. A daisy or a rose has radial symmetry; you could cut it in any direction and get a mirror image. We humans have bilateral symmetry. I just think we look at an orchid flower and think, oh my gosh, I see myself in that.”

Vanilla adds depth and nuance to our love affair with these unusual blossoms. The introduction to this article echoes an exercise Cameron conducts with his students, showing them vanilla is pervasive in daily life. Even if your favorite ice cream or preferred brand of shampoo doesn’t list vanilla as its star ingredient, it’s likely working behind the scenes to make these products possible.

“Coca-Cola contains vanilla,” Cameron says, though the recipes do not always use the same kind of vanilla, or the same amount. “They market different recipes of Coca-Cola around the world for different cultural palates.”

These varieties of vanilla — distinct flavor profiles not unlike personalities — are born from methods of curing that are unique to their region of origin. Indonesian vanilla, which is cured with fire, boasts a smoky, nutty flavor, while Tahitian vanilla produces the bright, fruity, floral notes sought after by bakers. Mexican vanilla, grown in the species’ native region, is dried in the sun and delivers notes of leather, tobacco, and black cherry.

“I just think we look at an orchid flower and think, oh my gosh, I see myself in that.”

“When you smell one of those beans, your eyes just roll back in your head,” Cameron says. “It’s so divine.”

This intoxicating scent is also inextricably linked to our memories. Vanilla often functions as the base of a fragrance due to its longevity over the course of wear. At the end of a romantic evening, long after citrusy top notes and peppery heart notes have faded away, vanilla lingers for the good-night kiss.

“There’s kind of this sensuality to vanilla,” Cameron says. “It has this allure to it.”

He describes artificial vanilla as “just a flat note” — a dull substitution for the vibrancy and complexity of the real stuff. And it’s the direction in which we are headed.

Prehistoric Plants

Although humans might harbor a sense of kinship with orchids, the vanilloid variety has bested us in age: while sequencing orchid DNA as a graduate student to understand evolutionary patterns, Cameron was among the first to find that Vanilla orchids germinated on prehistoric soil.

“Vanilla is supposed to be an advanced orchid, more highly evolved,” he says. “[However], my DNA evidence kept showing that it was one of the more primitive members of the whole orchid family — and there are 30,000 species of orchid. It’s the largest family of plants on earth.” So why — and how — has Vanilla assumed the title of eldest?

Further tests only confirmed Cameron’s findings: the genus Vanilla is one of the most ancient lineages in the orchid family.

Orchids’ endurance can be attributed in part to their steadfast resolve to adapt. While the earliest orchids may have laid roots in the ground, tropical orchids have evolved to reside in the extreme habitats of vines in tree canopies where heat and wind are plentiful, and rain is not guaranteed.

“Even here in Wisconsin, you often see orchids more commonly in disturbed places. They are growing along the edge of the path rather than in the grassland where they can’t really compete with the other plants very well,” Cameron says. “They’re always kind of on the margin of death and destruction.”

Crossing the Margin

In addition to teaching botany and overseeing the state herbarium, Cameron is the director of the conservation biology major at the UW. It’s a fitting position for a professor whose genus of expertise is both richly diverse and dangerously close to disappearing. Despite the hardiness that’s allowed the plant to exist across centuries, Vanilla orchids are in danger of extinction.

“All orchids are pretty much rare, but Vanilla, unfortunately, grows in the lowlands, often in wet places at low elevation, and those are the exact same places where humans have built our cities and where we do all of our farming and all of our development,” Cameron says.

Compounding environmental threats are the inherent challenges of tending Vanilla orchids, which grow on massive vines that require large support structures. Orchids are also botanical anomalies: they source their sustenance by stealing food from attacking fungi rather than deriving nutrients from their seeds, and they are limited in the pollinators they can pair with, as only a select few can access the flower’s straw-like vessel.

“What better epitomizes the web of life than this delicate, fine interrelationship of life forms?” Cameron asks. “You’ve got insects, orchids, fungi, other plants. They all have to be in perfect harmony for that orchid to survive. Once you break any of those connections, the orchid is gone.”

It’s this specialized process that has conservation biologists uncertain about the future of orchids. Vanilla is no exception.

“If you’re so highly specialized and you’ve come up with a strategy that’s unique to only you and has to work, you’re really kind of going out on a limb,” Cameron says. “That’s what makes a lot of us [wonder], ‘Are the orchids going to be able to survive?’ ”

Saving a Species

For the past 20 years, Cameron has dedicated his career to raising awareness of the diversity within the genus Vanilla to ensure its continued survival.

Of the more than 100 species of Vanilla orchids, only one of those, Vanilla planifolia — a flat-leafed variety that was first domesticated in pre-Columbian Mexico — provides vanilla flavor and fragrance. Today, cuttings of those original vines have been spread to different tropical regions (Madagascar now leads the industry in vanilla production), but different species of Vanilla orchids can be found on nearly every continent. It’s both a testament to Vanilla’s will to survive and a key factor in its projected demise.

“Here’s this crop plant that has never undergone any kind of hybridization or attempt to improve the crop,” Cameron says. “There’s no disease resistance because people are growing it as a monoculture — cuttings from the same original vines that the Spanish conquistadores took back to Europe in the 1600s — and lessons from history [tell us] that monocultures and lack of genetic variation in crop systems are a recipe for disaster.”

According to Cameron, Vanilla plantations around the world have already met their end at the hands of a single fungal pathogen. Still, the demand for Vanilla is higher than ever. As its value increases, both poachers and farmers are mistakenly harvesting wild varieties of Vanilla vines — devoid of fragrance or flavor — to sell for profit, placing those species’ survival in jeopardy.

This is where Cameron’s expertise becomes paramount: by educating growers about the genus, he hopes to conserve Vanilla’s natural genetic diversity, both by preventing reckless harvesting of wild species and by promoting crossbreeding of the domesticated plant in order to increase its resistance to pathogens. His book, Vanilla Orchids: Natural History and Cultivation, an out-of-print favorite among farmers and aficionados alike, details both the biology and diversity of the genus Vanilla and methods for harvesting and processing the domesticated plant’s fruit.

In addition to educating growers around the world, Cameron hopes that local conservation efforts can help to make a global impact. Some of these efforts are taking place right in his lab in the Department of Botany, in which he mentors students whose research answers the call to save these endangered species.

”What better epitomizes the web of life than this delicate, fine interrelationship of life forms?”

Currently, he is collaborating with Alexander Damian PhDx’26, a student from Peru who previously published a field guide of the native species of Vanilla found there, which face environmental challenges from mining and deforestation. In the Cameron Lab, Damian’s work expands upon this research to study the plants’ evolutionary patterns.

“Before my job in Peru, we were not sure how many species we had of these plants. Now, we have a better idea of where these plants are, and that’s a baseline to now take action to conserve those plants, or protect the habitats where they are living,” Damian says.

“Something that we don’t know yet is how these different species are related. … That’s my next step: to try to increase the sampling effort and apply some new sequence methods to understand how these different species evolve along the Andes, especially.”

Cameron is also turning his efforts toward species of Vanilla here in the United States in partnership with William Morton PhDx’22, a student studying the conservation genetics of Vanilla found in southern Florida, where climate change puts their habitats in imminent danger.

“The Florida Keys are very low-level islands, and the Everglades is a swamp; it’s already basically sea level,” Morton says. “Climatologists and NASA agree that if the rest of the glaciers of Greenland melt, the sea level could rise anywhere from 16 to 23 feet, and it would only take about eight inches for those environments in the Florida Keys — for [Vanilla’s] habitats — to be underwater.”

Part of Morton’s research includes developing a seed germination protocol that could offer more expedient and sustainable reproduction of these plants, in addition to suggesting other conservation methods such as assisted migration of the plants so that they don’t disappear.

“We just can’t lose hope,” Cameron says. “We have to keep trying and educating.”

Artificial Alternatives

There’s a silver lining to Vanilla’s fraught future, though it’s hardly sterling.

“We probably will always have a world with vanilla flavoring,” Cameron says. “But it might be artificial.”

Many manufacturers are already shifting to synthetic vanilla products. A genetically modified variety of bacteria produces vanilla flavoring that can be labeled as “natural” because bacteria are living, organic things.

“But it’s not the same product,” Cameron warns. “It doesn’t have the complexities and the special nuances of natural vanilla from the orchid.”

Perhaps, when we see ourselves in orchids, the familiarity goes beyond a vague reflection. We, too, have made a home on this earth for millennia but now see that home becoming a hostile environment. For orchids, this could mean the end of days. For their human counterparts, it’s pulling the sensory rug out from under the foods, customs, cultures, and memories that are wrapped up in vanilla’s aroma.

“Can you imagine a world like that?” Cameron asks. “What a tragedy it would be if we didn’t have vanilla.”

Megan Provost is a staff writer for On Wisconsin.