Coming Out in the Out of Doors

With a unique adventure program, Elyse Rylander '12 helps queer kids find a safe haven in nature.

When Elyse Rylander ’12 was a kid, being “out” meant sunbaked skin, scratched knees, and wide-open waters. Today, that word means so much more.

“There’s nothing straight about nature,” Rylander says. Trees are crooked and gnarled. Rivers meander. Hills rise and valleys fall. Nature embraces the irregular, the uneven.

It makes a home, Rylander argues, for things that are queer — and people who are, too.

“Oftentimes it’s physically impossible to even walk in a straight line because you’re always having to maneuver around something,” Rylander says. “I think for a group of people that is culturally told, either implicitly or explicitly, that they’re not natural, to be able to go out into the natural world and see queerness all around you is probably one of the most empowering experiences, especially for a young person.”

Rylander has made a career and a life in nature. What started as a space for childhood adventure and freedom to roam became a safe haven to explore and embody her queer identity. Now, Rylander offers this experience to her “kiddos” — LGBTQ+ young people searching for themselves through her organization, Out There Adventures. Rylander is out, and is helping give others that freedom, too, in a space where being out is the most natural thing in the world.

Wild Child

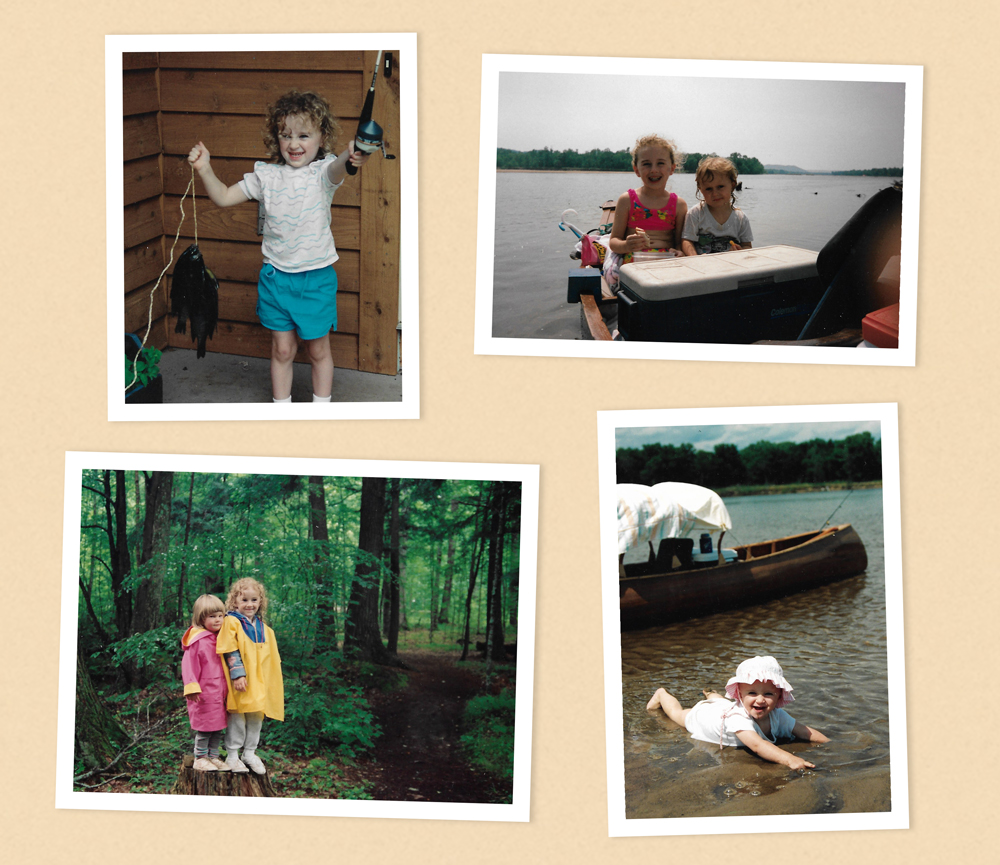

Rylander was born to be wild — literally. She was only four weeks old when she took her first canoeing trip down the Wisconsin River (in a homemade, cedar-strip canoe, no less), and she has been living more out of doors than in ever since.

Growing up on her parents’ 12 acres near Poynette, Wisconsin, Rylander spent her childhood bound only by how far her family’s adventures and her own wanderings could take her.

“We were definitely those kids that go outside after breakfast and don’t come home until dinner,” she says.

Summers off with her mom, a teacher at the local high school, meant camping up north near her grandparents in Mercer, while snowy white winters sent her down the ski slopes of Cascade Mountain in Portage.

“We’re very much of modest means,” Rylander says. “We were not a family that took vacations to Florida or Disneyland or anything, but we spent just a ton of time outside in more of a local sense. I joke that I’ve been to every boat landing north of Wausau, because we would just go frog around for weeks on end in the summertime.”

When she wasn’t blissfully lost in the wilderness or out on open waters, Rylander’s childhood was set against the backdrop of down-home, everybody-knows-everybody Wisconsin in which someone’s mom was on every street corner, and Friday night football was a town affair. It could be cozy, and it could be intimidating.

Clockwise from top left: Rylander at age 3 on Lake Wisconsin; at age 5 with sister Eliza on the Wisconsin River; at age 1 with cedar strip canoe; and with a cousin at age 4 on a family camping trip. Courtesy of Elyse Rylander

This social setting grew more constricting as she came to terms with her own identity. From a young age, she recognized that she was queer.

“[As a kid] I remember having a really fat crush on Kimberly, the pink Power Ranger, and it manifested for my parents as that I wanted to be [her]. I was like, no.”

Her mother, Robyn, hasn’t forgotten.

“She had this weird obsession with the pink Power Ranger,” she says. “The white Power Ranger was a boy, and his name when he wasn’t a Power Ranger was Tommy; she went through a stage where we could only call her Tommy. We couldn’t call her Elyse.”

However, a lack of conversation surrounding the topic of being queer kept Rylander in the closet throughout her years at Poynette High School.

“It was just such a non-conversation that I didn’t even really think that [coming out] was an option,” she says.

Not wanting to rock the canoe, Rylander adhered to the image of other teenagers in her school: she wore Abercrombie & Fitch; she shopped at Hollister; she maintained an image that was palatable to her small community.

“I mean, forget being gay,” she says. “There was one out girl that I went to high school with, and it seemed to be absolutely terrible for her. It felt like it would have been social suicide to come out.”

Still, Rylander says that both her family life and her time spent in nature were spaces of support and freedom of expression. “You’re on vacation and you’re in the middle of the woods. Nobody cares how you’re presenting yourself.”

Activities like kayaking, camping, and foraging offered Elyse and her sister, Eliza, a sense of accomplishment and an opportunity for confidence-building that, paired with her parents’ unwavering support, she considered unique.

“It just felt really cool to be a young girl doing those things,” Rylander says. “There was more of a sense of confidence-building around our gender identity, [but] that was never explicitly articulated. That was just an ethos that my parents were able to live out.”

Rylanders Bleed Red

Camping and canoeing aren’t the only traits that run in Rylander’s family: they hail from a long line of Badgers. Thanks to Poynette’s proximity to Madison, Rylander spent the early part of her life attending Badger basketball and football games with her dad, biking Picnic Point, and eating Babcock ice cream on sunny Terrace days. Attending the university was a natural next step for her after high school.

However, when it came time to apply, she was terrified.

“I got an early acceptance from [the University of] Minnesota, and I was like, ‘I don’t want to be a Golden Gopher! Please don’t make me go!’ ” she says.

Her nerves didn’t settle until, finally, mail came from Madison.

“I remember getting the big envelope that had the ‘yes’ on the back,” she says, “and I was like, ‘WAAAA!’ I was so ready to leave Poynette and to be [in Madison].”

It wasn’t just long-held family tradition that drew Rylander to Madison. The city offered a refreshing anonymity.

“Being able to kind of start over and reinvent myself was something that I absolutely wanted and needed, so it was not at all overwhelming to be one of 40,000,” she says.

Despite relocating to the city, Rylander didn’t stray from nature for long. She took a job as a kayaking instructor at Rutabaga Paddlesports in Monona, where she met Mo Kappes, an instructor and openly gay woman. Kappes would later join the UW campus as the director of Adventure Learning Programs, which Rylander was involved with as a student.

“She was so calm and cool and just felt so self-assured. I was like, ‘This is what I want to be,’ ” Rylander says. “I had never really had much interaction as a burgeoning adult with queer folks that were like, ‘Yeah, it’s totally fine. Jump in, the water’s great.’ ”

Rylander (far left) and her wife, Emily (far right), lead an Out There Adventures cohort on a backpacking trip in the North Cascades in Washington State.

Although the UW offered a queer community, Rylander says she was never interested in spaces like the Gender and Sexuality Campus Center or groups like Gay-Straight Alliance.

“I think my initial coming out was very much an assimilationist sort of view. I just wanted to fit in,” she says. “I remember walking around campus with Mo one time and having a conversation of, ‘I don’t know why all these queer folks have to be so fight the power and intense with it. Just chill out. Try to blend in.’ ”

With Kappes’s guidance and her own growth, Rylander quickly shed this mind-set.

“I look back and I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe I said that,’ ” Rylander says. “But I had so much internalized homophobia, and I was so afraid of being chastised or physically harmed.”

Kappes also recalls Rylander feeling “not queer enough” for the UW gay community.

“There’s no one way to be gay,” she says, “and you can’t be gay enough or not gay enough. You are who you are. … If [others] feel like you have to be a certain way to be gay enough, then that’s on them.”

In the small and supportive environment of a first-year interest group, a freshman-only course titled The Psychology of South Park, Rylander openly identified for the first time as a queer woman.

“I think there was definitely a part of me that was wanting to feel adventurous or take that sort of leap in that way,” she says. “But more so, I think it was … sort of a litmus test of how this [was] going to go.”

After coming out to close friends throughout the school year, she decided it was time to tell her parents when she went home for the summer. In a conversation in the kitchen with her mom, she hinted that her “friend” from school was actually her girlfriend.

“My mom had this tray of muffins, and she dropped one hip and she went, ‘Oh, honey, you really think we didn’t already know?’ And then just put the muffins in the oven and proceeded with her day.”

Robyn remembers the moment just as clearly as she does the fear she felt for her daughter’s safety.

“[I was] so scared that she wouldn’t be able to be who she is and live in her own skin because somebody might harm her,” Robyn says. “I still worry about it.”

When Rylander told her father what apparently was not news to anyone in the family, his response was a question: “Why did we spend all that money on prom dresses?”

“Lesbians can go to prom, too, Dad,” Eliza quipped.

Rylander was now out: out of the closet, out of Poynette, and as often as possible, out in nature.

This One’s for the Kiddos

Rylander graduated with a degree in communication arts and gender and women’s studies and a certificate in LGBTQ+ studies. While friends and family alike were skeptical of the value of a women’s studies degree, Rylander has found it to be essential to her professional goals.

“I can’t talk enough about how much my time at Madison created so many different opportunities and opened doors and thoughts,” she says.

It was in a capstone course for her LGBTQ+ studies certificate that Rylander began to formulate her current endeavor: Out There Adventures (OTA).

“A lot of folks were self-selecting out of traditional outdoor-ed programs for fear of being ostracized,” she says. “Knowing what a profound impact that time outside had for me, especially when I was coming to terms with my queer identity, [I wanted] to be able to help other kiddos have that access as well.”

Rylander moved to Seattle to tap into the outdoor community of the Pacific Northwest. She launched her nonprofit in 2014, with a mission to create a space in which LGBTQ+ youth can explore and inhabit their own identities. OTA’s first cohort of two “kiddos” and two instructors set out in June 2015 for paddling in the San Juan Islands.

“I worry sometimes people may feel it’s infantilizing,” Rylander says of her term for the young people she works with, “but for me it’s a term of endearment. … Kiddos does imply an age difference, but one that comes with the responsibility of wanting to care for them as I would my own.”

According to Rylander, the emotional and community-building aspects that render OTA unique among outdoor-adventure organizations grow organically from the youth who take part in its programming.

“Really, it’s about helping them to foster a sense of resiliency and self-confidence to advocate for themselves out there. That’s what everyone with a marginal identity has to do, because we don’t yet live in a world that is truly inclusive,” she says. “That idea of resilience is really key in helping them to understand that having an underrepresented or a marginalized identity can be your key to success and can be your power — your superpower.”

“She’s maybe the most fun person I’ve ever co-instructed with,” Ryland says of wife Emily (far left). “She’s the person you want to have when group morale is low because she can turn it around real quick.”

Outside of adventure-oriented activities, OTA enacts what Rylander calls a queericulum, a model that “permeates every aspect of a course that keeps queerness at the center.” Elements include changing the gendered pronouns and names in stories told about natural processes in order to make these narratives more culturally relevant to LGBTQ+ folks, creating spaces to try out new names and pronouns, and allowing time to navigate male–female binary bathrooms, which are not always welcoming to other gender identities.

“What Elyse offers is this academic or philosophical knowledge base about queer theory [beyond] just [her] lived experience,” Kappes says. “That’s why I think OTA is unique.”

According to Kappes, Rylander is a model for fostering empathetic and inclusive spaces. “That takes intentionality and understanding and knowledge,” Kappes says. “She can bring that.”

For Rylander, that process starts with the same self-reflection she practices with her kiddos. “You have to unpack your own stuff as it relates to everything and [get] a good handle on who you are and your blind spots and your biases, because we all have them,” she says. “If you come to the table with a better sense of self and truly wanting to be an accomplice in the work, then when you do make a mistake, as we all will, people are far more inclined to support you through that process.”

Despite the rich experience that Rylander has cultivated for OTA participants, she says her own fear of coming out would have prevented her from taking part in such a program had it existed during her own formative years.

“I think knowing that the opportunity existed probably would have been a benefit. But I don’t think I would have been able to experience the benefits of actually participating,” she says.

That’s why Rylander presents nature as a space in which nothing is straight, and in which queerness flourishes organically — as it does in the kiddos for whom she offers a way “out.”

And it doesn’t hurt that nature — with all its twists, trials, and triumphs — brings out strength.

“There is something that is so profoundly empowering,” Rylander says, “when you can go, yeah, I’ve dealt with some stuff, and I have always come out on the other side. So perhaps I feel as though I won’t make it up this next thousand-foot gain, but I’ve done other really difficult things, so why can’t I be successful in this moment?” •

Megan Provost, a former On Wisconsin intern, is now happy to be contributing as a staff member.

Published in the Winter 2020 issue

Comments

Steve March 19, 2023

Hi Megan. Your article on “How To Have It All” brought back a flood of memories, some good… some not so good. I remember my freshman year in Madison, while attending the U of W, for two main reasons. 1. I was at the UW on a 4 year baseball scholarship, on track to play pro-ball, which was my life dream since I was 10 years old. Sophomore year I played for one summer with the Milwaukee Braves. 2. Ironically, although I was living my dream, I began to experience a vacuum in my life that encompasses everything. Happiness was no-where to be found, but the emptiness was getting bigger and bigger. I asked myself a thousand times what am I doing wrong? Is this really all there is to life? Working with special needs kids and helping other students only created a “happiness” that lasted less than a few seconds.

One day a friend told me what Blaze Pascal once said. “There is a God shaped vacuum in the heart of every man which cannot be filled by any created thing, but only by God, the Creator, made known through Jesus.” ( I know others have tried changing what Pascal said) When I heard this I thought two thoughts at the same time: 1. You mean there are other people that have an emptiness in their lives? 2. What in the world does God have to do with it? I have always believed in God! It wasn’t until I finally developed a relationship with God that the vacuum in my life disappeared in a heartbeat, and a fantastic and foundational peace now fills my life. Anything I do now to help others is done because of the peace I now have and not the other way around! The “God peace” far surpasses any happiness the world has to offer. There is no higher happiness than peace. In addition, the world can’t take away that peace…because the world did not give it to me.

I have a few questions: 1. You have done a lot of research, thank you, in putting your great article together. There are millions of stories similar to mine. Why were none of these quoted as a source for the ultimate happiness? 2. Do you think there is a God? 3. Do you think it is possible that people are at an all-time “happiness low”, as noted in your article, due to the fact that God has basically been removed from our schools, homes and public places? 4. Could the emptiness that everyone has, be built into the human race as God’s way of drawing people to Him, and, in reality, we are wasting our time trying to fill it with earthly happiness?

Thanks again for the great article.

Steve Tadevich 608-334-5086