Chamber of Discovery

An astounding find in South Africa adds a new branch to the human family tree.

The first clue was a skull spotted by amateur cavers as they descended deep beneath the ground of South Africa.

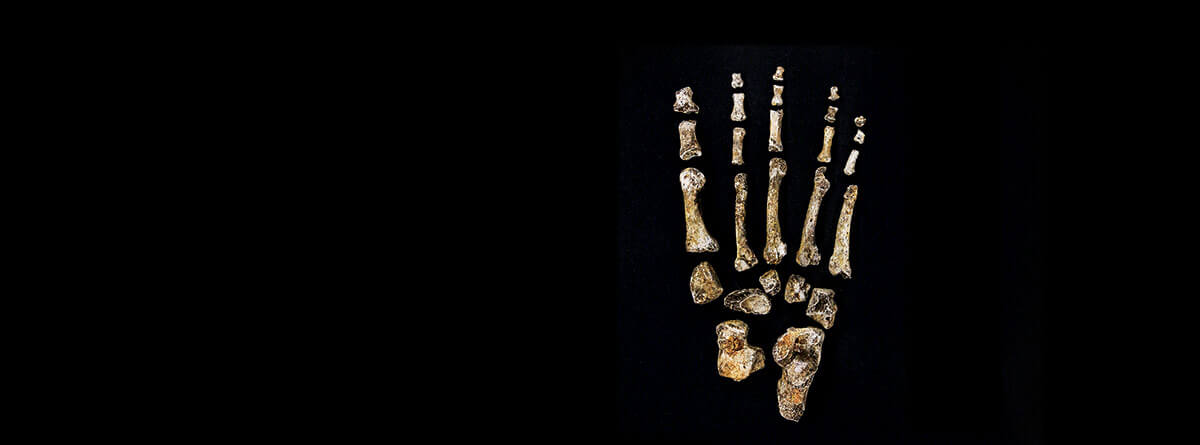

Before long, an international team of scientists, including a UW paleoanthropologist, undertook a remarkable task, bringing to light an unprecedented trove of fossils — more than fifteen hundred well-preserved bones and teeth that represent the largest, most complex set of such remains found to date on the continent.

They weren’t just any old bones. Writing in two scientific papers published in September, the scientists revealed that the discovery adds a new branch to the human family tree, a creature they dubbed Homo naledi.

They weren’t just any old bones. Writing in two scientific papers published in September, the scientists revealed that the discovery adds a new branch to the human family tree, a creature they dubbed Homo naledi.

And there’s more: the fossils — first discovered in 2013 in a barely accessible chamber, a labyrinth one hundred feet underground not far from Johannesburg — could only have been deliberately deposited, a behavior by these very early human ancestors that suggests culture. It’s a supposition akin to discovering similar activities among chimpanzees, says John Hawks, a UW professor of anthropology and one of the team’s leaders. “It would be that surprising,” he says.

15 At least this many skeletons — representing all ages — were found within a chamber of the limestone caves near the Cradle of Humankind.

150 The approximate number of countries with readers who clicked to view a UW website that launched when the Homo naledi story went public in September.

When announced to the world, the discovery sparked international interest and was covered by National Geographic (the project’s main funder), 60 Minutes, the Guardian, Slate, National Public Radio, the New York Times, the BBC, and many other news outlets.

So far, parts of at least fifteen skeletons representing individuals of all ages have been found, and the researchers, led by paleoanthropologist Lee R. Berger of the University of Witwatersrand, believe many more fossils remain. The chamber is part of a complex of limestone caves near what is called the Cradle of Humankind, a World Heritage Site in Gauteng province well known for critical discoveries of early humans, including the 1947 discovery of 2.3 million-year-old Australopithecus africanus.

“We have a new species of Homo, with all of its interesting characteristics,” says Hawks, adding that the find is the “biggest discovery in Africa for hominins,” a subfamily of the taxonomic system that includes humans.

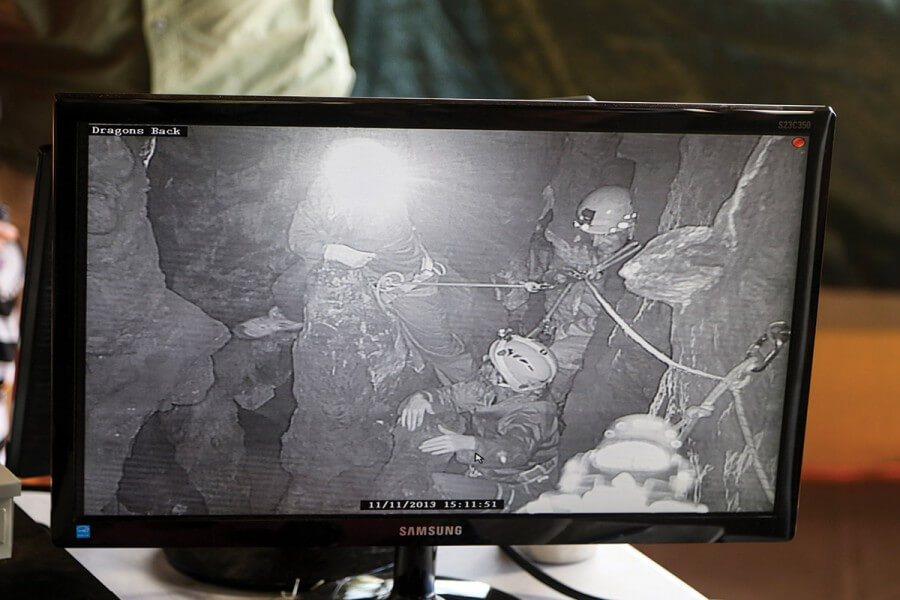

As specially recruited cavers make their way through narrow passages to reach the underground chamber, a live video feed (above) shows scientists on the surface their progress — and, ultimately, what they are discovering. Alia Gurtov, a UW anthropology graduate student and one of the cavers, says that the number of pieces of bone they found on the floor of the chamber was “like pick-up sticks. You couldn’t get one thing out without excavating something else.” John Hawks

The Rewards of Being Small

The Facebook query was exacting and cryptic: “We need perhaps three or four individuals with excellent archaeological / paleontological excavation skills. … The catch is this — the person must be skinny and preferably small. They must not be claustrophobic, they must be fit, they should have some caving experience, climbing experience would be a bonus …”

Alia Gurtov MS’13, a UW anthropology graduate student, fit the bill. Read more »

Homo naledi — with a small head and brain, hunched shoulders, powerful hands, and thin limbs — was built for long-distance walking, says Hawks, an expert on early humans. Fully grown, it stood about five feet tall, was broad chested, walked upright, and had a face that included a smile that was probably more human than apelike. The powerful hands imply that it was also a climber.

The fossils have yet to be dated. The unmineralized condition of the bones and the geology of the cave have prevented an accurate estimate, says Hawks. “They could have been there 2 million years ago or 100,000 years ago, possibly coexisting with modern humans. We don’t yet have a date, but we’re attempting it in every way we can.

“We depend on the geology to help us date things, and here the geology isn’t much like other caves in South Africa,” he continues. “And the fossils don’t have anything within them that we can date. It’s a problem for us.”

One hope, he says, is finding the remains of an animal that may have been a contemporary of Homo naledi. The fossils are embedded in a matrix of soft sediment and there are layers that remain unexcavated.

The remains represent newborns to the aged. The researchers expect that many more bones are yet to be exhumed from the chamber, which is accessible only after squeezing, clambering, and crawling six hundred feet to a large space where the brittle fossils cover the floor.

“We know about every part of the anatomy, and they are not at all like humans,” says Hawks, who co-directed the analysis of the fossils. “We couldn’t match them to anything that exists. It is clearly a new species.”

Dawn breaks at the Rising Star Expedition campsite near Johannesburg, South Africa, as the project team readies for another day. The project was supported by the National Geographic Society, the South African National Research Foundation, and the Gauteng Provincial Government. The Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation also provided support, as did the Texas A&M College of Liberal Arts Seed Grant Program. John Hawks

Naledi means star in Sesotho and refers to the Rising Star cave system that includes the Dinaledi Chamber, where the fossils were found. The circuitous and difficult passage to the chamber narrows at one point to a mere seven inches. The fossils were retrieved by a group of paleoanthropologists who were recruited in part for their diminutive size.

Video

In addition to identifying an entirely new species in the genus Homo, the fossils, which bear no marks from predators or scavengers, are strong evidence that Homo naledi were deliberately interring their dead. “We think it is the first instance of deliberate and ritualized interment,” says Hawks. “The only plausible scenario is they deliberately put bodies in this place.”

The cave, he says, was likely more accessible to Homo naledi than it is for modern humans. Geochemical tests, however, show that it was never open to the surface, raising intriguing questions about the behavior and technologies available to Homo naledi. “We know it was not a death trap,” Hawks says, referring to natural features such as hidden sink holes that sometimes trap and doom creatures over long periods of time. “There are no bones from animals, aside from a few rodents. And there are no marks on the bones from predators or scavengers to suggest they were killed and dragged to the chamber. We can also rule out that it was a sudden mass death.”

Instead, Hawks, Berger, and their colleagues believe that the chamber was a place where Homo naledi routinely secreted their dead companions. The way the bodies are arranged and the completeness of the skeletons suggest they were carried to the cave intact. “It seems probable that a group of hominins was returning to this place over a period of time and depositing bodies,” Hawks says. “The bodies were not intentionally covered, and we’re not talking about a religious ceremony, but something that was repeated and repeated in the same place. They clearly learned to do this and did it as a group over time. That’s cultural. Only humans and close relatives like Neandertals do anything like this.”

The team has yet to find other organic materials or evidence of fire in the cave complex.

Hawks says plans include calling upon many new technologies to analyze the fossils, helping to determine diet, rate of aging, and Homo naledi ’s home region.

Years of work remain both on and off site. The researchers will continue to excavate new materials and carefully analyze the remarkable find, unlocking secrets of a long-ago human ancestor.

Slideshow: Chamber of Discovery

Six scientists, all small in stature, were specially recruited for the expedition, which at first was thought to involve investigating a single hominin skull. “You’re in this initial chamber, and then you have to squeeze through a crevice that opens into [another] chamber. ... We knew there was a skull in there. We had no idea we were going to find more than that,” says Alia Gurtov, a UW anthropology graduate student, second from left.

Prepping for travel, researchers carefully wrap the bones and pack them into plastic containers after removal from the cave’s wet sediment. Excavation followed forensic techniques (often using toothpicks) prescribed by paleontology. First collected in November 2013, the bones are now housed at the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of Witwatersrand, where they are being carefully measured, documented, studied, and reconstructed.

Huddled around project leader Lee Berger’s computer on site in South Africa, the researchers intently watch via video.

“None of this goes together the way we expected,” says Caroline VanSickle (left), a UW postdoctoral fellow who is working with colleagues to piece bones together into a coherent whole. “Homo naledi has this weird combination of traits that we wouldn’t have expected to see together.”

A handwritten sign marks territory on a small table where researchers are carefully making sense of the brittle bones found so far. Sharing the table are colleagues studying the thorax, and nearby working spaces are dubbed Hand Land and Tooth Booth.

John Hawks, a UW professor of anthropology who is codirecting analysis of the fossils (right), works with Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist from a South African university who is leading the Homo naledi project.

Published in the Winter 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.