A Story of Almosts

Lee Kemp '79, MBA'83 is the greatest wrestler you've never heard of.

It’s easy to get hyperbolic about athletes. Easy to overstate their greatness, easy to claim “best ever” in profiles, career retrospectives, and documentaries. This is not one of those profiles. Lee Kemp ’79, MBA’83 is one of the greatest. Ever. But Kemp’s in-credible wrestling career is one of almosts: a few big things that almost didn’t happen —and one huge thing that almost did. Those who are even tangentially connected to the sport know his name, but because of a political decision made nearly 40 years ago, the rest of America doesn’t.

Almost Basketball

Leroy “Lee” Kemp Jr. was not his name at first; he was Darnell Freeman until Leroy and Jessie Kemp adopted him at the age of five. Growing up in Cleveland, Ohio, Kemp was surrounded by black neighbors and basketball — and, eventually, racial strife and violence, which prompted his family to move about 30 miles east of the city to the small community of Chardon, Ohio. That was the first of the almosts.

“Had I stayed in Cleveland, I actually would not have wrestled,” Kemp reflects. “It wouldn’t have been something I thought about.” But his new hometown of Chardon was small, mostly white, and mostly agricultural —the kind of town where wrestling thrives.

Sticking with what he knew, Kemp joined his junior high school’s basketball team. It didn’t go well. “In two years, I think I maybe played five minutes,” Kemp recalls. When he got to high school and joined the freshman basketball team, he didn’t play in scrimmages. Frustrated, he yearned for something different.

That’s when, on his way to basketball practice, he walked past the wrestling room. “I stopped and just stared into the window, watch-ing the wrestlers practice.”

He skipped basketball practice to watch wrestling, which got him kicked off the team —but it worked out just fine. Kemp, weighing about 138 pounds at the time, was welcomed by a wrestling coach who just so happened to need a wrestler in the 138-pound class. Two weeks later, Kemp hit the mat and won his first match.

“That feeling of exhilaration —of winning one-on-one —was amazing,” he says.

He lost only twice that year and won the conference title for freshmen. As a sophomore, he made varsity and went 11–8–3, but he wanted to do better.

A Turning Point

In the summer of 1972, after Kemp’s sophomore year, there were few wrestlers more famous than Iowa State alumnus Dan Gable. With two NCAA championships and one world freestyle title, Gable was America’s best hope against the unbeatable Russians for an Olympic gold medal at the Munich games. He dominated the Olympic trials, pinning three of four opponents on his way to the gold. And he made an appearance at a camp that summer —a camp that Kemp attended. Kemp had watched Gable’s Olympic victory on television, and he was inspired.

“I started to try to figure out a way that I could train like him, and hopefully be like him,” Kemp says. “I didn’t lose a match after that.”

That’s right — after deciding to train like the great Dan Gable, Kemp never lost again in high school. That success, of course, caught the attention of college recruiters — which is another one of those “almost” moments. Kemp almost didn’t come to Wisconsin.

Many of the Ohio wrestlers Kemp admired went to Michigan State, but the school couldn’t offer him a full scholarship, so Kemp’s father told him to keep looking. Then came a family friend, John Grantham, who encouraged Kemp to visit the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Meanwhile at the UW, Athletic Director Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch x’45 had instructed wrestling coach Duane Kleven ’61, MS’63 to make an offer to the up-and-coming state champ from Ohio.

Kemp committed to the UW with an audacious goal — to become the first four-time national champion in NCAA history. And he almost did it, too. He didn’t lose during his entire freshman season — a practically unheard-of feat — reaching the finals of the NCAA tournament, which went into overtime. In those days, overtime was three one-minute periods with three referees watching; if the score remained tied after three minutes, the referees would declare a winner based on who they thought had wrestled better.

Kemp lost on a 2–1 vote, which motivated him more than ever. The proof? He never lost another collegiate match.

The Upset

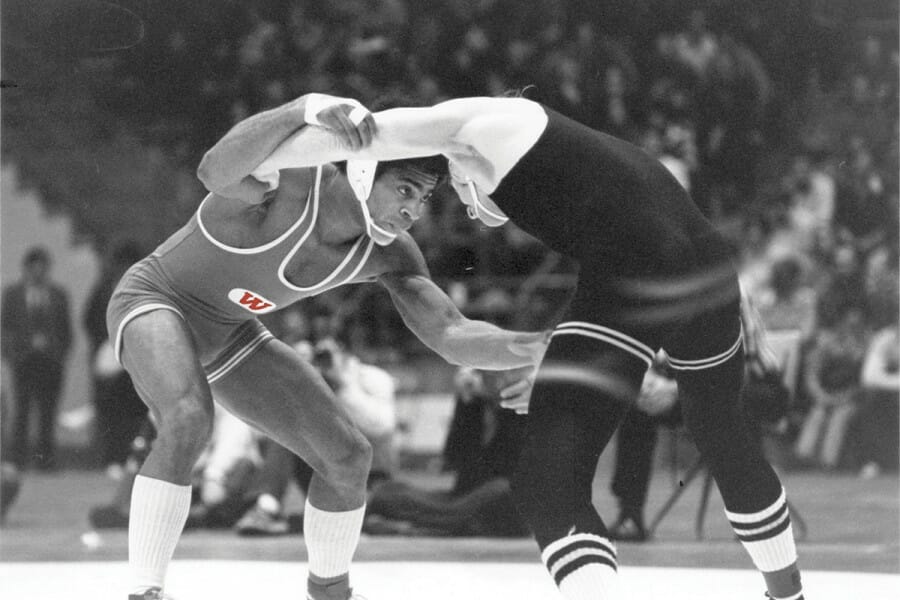

In the midst of his sophomore season, Kemp entered the Northern Open, an amateur tournament hosted at the UW. There was a bit of a buzz: Dan Gable, coming out of retirement at 26 to make a run at the 1976 Olympics, had entered the tournament. In Kemp’s weight class.

Kemp’s coaches and teammates tried to talk him into dropping down a weight class just for this one tournament, to avoid having to lose to Gable. Kemp wanted none of that. “It was a challenge that I embraced,” he says. “I wasn’t afraid of it.”

Only grainy black-and-white video exists of that match. It’s a scrappy one —mostly takedowns and escapes. Neither wrestler could be held down for long. With an improbable 7–6 lead in the third period, Kemp found himself in a difficult spot. With a little less than a minute to go, the two were still upright, but Gable had Kemp’s leg. A twist of the hips and Kemp would be down; Gable would win. But Kemp managed to hook his arm under Gable’s shoulder and stay upright, preventing the Olympic gold medalist from gaining control. Kemp held Gable off for 30 agonizing seconds. The clock ran out, the buzzer sounded, and the Wisconsin Field House erupted. Kemp had done the unthinkable —defeated his idol. Everyone’s idol.

The win put the wrestling world on notice. This 18-year-old black kid from Ohio was the real deal, and potentially good enough for the Olympics. Kemp, however, saw it as just another win —one of many to come. “Some people have … one match that they did great in, and then that’s what they kind of hang their hat on for the rest of their wrestling career,” Kemp says. “I didn’t want that. I just wanted to go as far as I could go.”

As far as he could go seemed to be Olympic gold.

What Almost Was

“Wisconsin was a good place for me. No question about it,” Kemp says. It was where he won three NCAA titles and, in 1979, graduated with a degree in marketing. He stuck around after graduation, preparing for the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. He was never really challenged in the trials and seemed poised to go beat the Russians on their own mats.

Then the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter announced that theUnited States would not send an Olympic team to Moscow —and just like that, the dreams of hundreds of America’s elite athletes were crushed. “I have compared it to the death of a loved one,” Kemp says. “You can never get that person back. You mourn, and I mourned. You cry. You’re upset. You move on, but the loss is still there.” (It is an unfortunate parallel that now, exactly 40 years after the Moscow boycott, hundreds of American athletes —and thousands of others from around the globe —will experience the same disappointment. In March of this year, the International Olympic Committee postponed the 2020 Tokyo games due to concerns about COVID-19.)

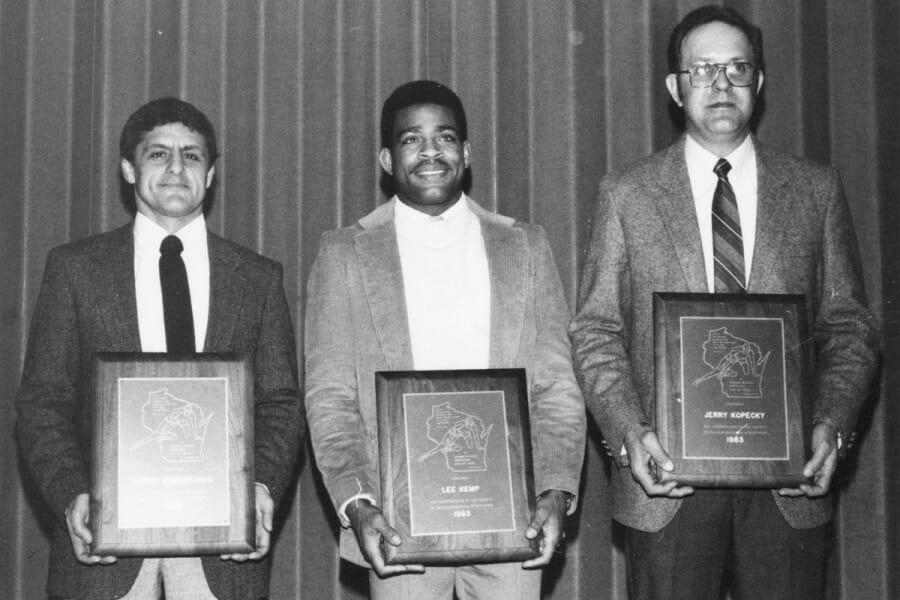

Kemp didn’t give up after the 1980 cancellation, though; he stayed in Madison, training with the UW team while also earning his MBA from the Wisconsin School of Business. His eyes were on the next Olympics: 1984 in Los Angeles. Leading up to the trials, Kemp became one of the most decorated wrestlers in American history, bringing home gold medals in three world freestyle championships, four Wrestling World Cups, and two Pan American Games.

But those medals didn’t matter when it came down to the Olympic trials. Kemp faced off against a young up-and-comer named Dave Schultz —whom Kemp had defeated in the 1980 trials and nine other times. This time, Schultz came out on top, and he went on to win the gold at the 1984 Olympic games.

Kemp knows that his life would have been different had he gotten that elusive Olympic fame. Athletes can become well known in their sport, but it’s the Olympic gold that makes them world famous. “You can let that consume you and defeat you, and you could complain about it for the rest of your life. And I do still complain about it,” he admits. “I’m not completely over it, but the fact is you do have to move on somehow.”

After the defeat in 1984, Kemp hung up his wrestling shoes and turned his attention to business. He leveraged his MBA into a successful marketing career, first with Clairol and then in Ford’s minority dealer program, through which he opened a Ford dealership in Minnesota. There, he started a family, and for almost 20 years, wrestling was a thing of Lee Kemp’s past.

A Rekindling

A tumultuous divorce in 2007 led to Kemp staying with his longtime friend John Bardis, also a former wrestler and a business owner. Seeing Kemp adrift, fighting for custody of his three children (which he eventually won), Bardis encouraged him to seek refuge in his first love: wrestling. At first, Kemp resisted, thinking it would be a step backward. “He could see that maybe I needed wrestling,” Kemp says. “I needed something to make me feel better about myself again.”

Bardis invited Kemp to attend the World Team Trials in Las Vegas. “It was like a homecoming,” Kemp says. He jumped right back into the sport —this time as a coach. He joined the coaching staff of the U.S. national team in 2006 and 2007, and he coached at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

A 2019 documentary, narrated by actor Billy Baldwin, tells the story of Kemp’s career. Kemp also wrote a motivational book titled Winning Gold. See leekemp.com for more information.

He’s a wrestling dad now, too: his youngest son, Adam, earned a scholarship from Fresno State. Kemp left the Midwest and moved to California to be closer to his three children, and he now coaches at Sacramento City College and travels the country as a motivational speaker. Most recently, Kemp helped produce and promote a documentary called Wrestled Away: The Lee Kemp Story. The 2019 film, narrated by actor and wrestling enthusiast Billy Baldwin, features archival footage of Kemp in action, in addition to the voices of his opponents, his coaches, and his friends — including those who encouraged him to consider becoming a Badger 45 years ago.

Getting back on the mats as a coach not only brought Kemp a sense of peace, but also returned him to peak physical condition.He says the athleticism of wrestlers has skyrocketed since he started nearly 50 years ago. But he knows it’s not athleticism that makes a great wrestler. What makes one great at the world’s oldest sport is entirely mental, maybe even spiritual.

“The biggest thing is the ability to face adversity,” Kemp says. “In team sports, you face it with other team members. [In wrestling], you are 100 percent responsible for your actions. … Very few things in life are quite that cut and dried, where it’s all you,or it’s all your opponent. There is no middle ground.”

Today, Kemp still feels a pang of regret every four years when the Summer Olympics come around. But looking back on his unlikely journey, he is content. Olympic medal or not, the world of wrestling will remember the name Lee Kemp Jr.

Robert Chappell is an associate publisher at Madison365. A longer version of this story originally appeared in Badger Vibes, a digital newsletter created in a partnership between the Wisconsin Alumni Association and Madison365.

Published in the Summer 2020 issue

Comments

Richard Fox February 2, 2022

What a wonderful Man and athlete, who’s life was short changed by politicians. It is a lesson and reminder to us all!