A Hero Comes Home

The UW's MIA Project collaborates with the Department of Defense to return the remains of a World War II pilot missing for 75 years.

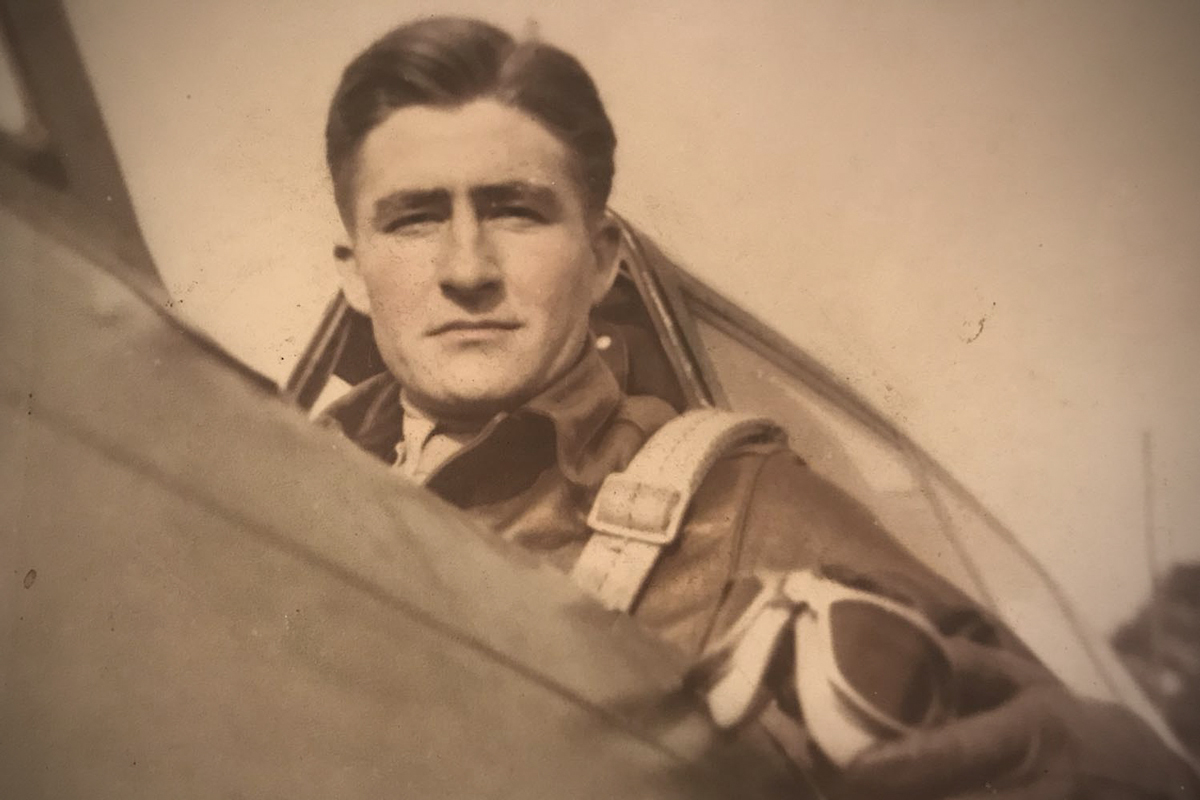

Surrounded by the roar of his P-47 Thunderbolt and buried in a bank of clouds that had cut visibility to less than 100 feet, 2nd Lt. Walter Stone was far from home.

It was October 23, 1943, and the whiteout in the sky had separated Buster — as he was known back in Andalusia, Alabama — from the rest of his Army Air Force 350th Fighter Squadron and the flight of B-26 Marauder bombers they were escorting to targets near Cambrai in Nazi-occupied northern France.

After the trip hundreds of miles down England’s eastern coast, the leader of the bomber mission had scrubbed the attack run. It was pointless in the soup they encountered near Saint-Omer. They would regroup and head back across the English Channel.

Escorting bombers may have been the assignment Buster sought out from the beginning, when he was one of James and Lilla Stone’s four sons who joined the armed forces as the United States entered World War II.

“One of his brothers was a navigator in the big bombers,” says Mark Stone, the pilot’s great-nephew. “In his mind, his brother was in one of those bombers he was escorting. Everybody in our family has heard stories like that about Buster.”

On October 23, 1943, Stone was assumed crashed while escorting B-26 Marauder bombers over Nazi-occupied northern France.

He was 24, not far removed from his Pleasant Home School graduation and marriage to Miriam Boyette. Buster was well liked and respected, a young man who, like so many others, interrupted his life to do his duty for his country.

“My daddy and his daddy watched Uncle Buster kiss his wife goodbye there in Andalusia,” Mark says. “My daddy watched his daddy embrace his brother and then put him on a plane to the war. They were the last family members to see him.”

Unlike his three brothers, who would return safely, Uncle Buster would live on only in stories. The last his squadron-mates heard from him, he was heading for England and would see them on the ground. But 2nd Lt. Stone never came out of the clouds.

His plane was assumed crashed, and he was declared missing in action. Eventually his name was added to the Tablets of the Missing at the Ardennes American Cemetery in Belgium and to the list of American fighters killed but still not recovered. But a piece of him stayed alive back in Alabama with Lilla and the large and tight-knit Stone family.

“His mother — we all called her Mama Stone — had a memorial for him put in the family cemetery plot by the church in Andalusia,” says Mark. “She never gave up hope that Uncle Buster would come home. She talked about it until she died, and she was buried right by that memorial.”

Buster was buried somewhere in France, but it would take nearly 75 years and a team of volunteers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Missing in Action Recovery and Identification Project to prove Mama Stone right.

“The Least You Can Do”

Organized by UW–Madison researchers skilled in identifying ancient and degraded genetic material, the MIA Project in 2013 helped the Department of Defense identify the remains of Private First Class Lawrence Gordon, who was killed in Normandy in a firefight with retreating Germans in 1944 and incorrectly buried as a German soldier.

In 2016 and 2017, the MIA Project broke ground near Buysscheure, France, as the first academic partner of the Department of Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), the agency tasked with accounting for the country’s missing service members. An MIA Project crew carefully excavated a farm field for several weeks in consecutive summers until they had conclusively identified the plane and then recovered the remains of another missing young World War II pilot, 1st Lt. Frank Fazekas.

“It’s not the kind of thing you want to do just once,” says Charles Konsitzke, associate director of the UW Biotechnology Center and facilitator for the MIA Project. “When you think about how many are still missing — more than 72,000 just from World War II — and how every day there are fewer of their friends and family members left to remember them, you feel a great sense of urgency to take on the next case.”

In the spring and early summer of 2018, the UW team went to work on a pool of new cases. They would need to be ready to travel, to acquire permits to work on public or private land, and to have a plan in mind for a dig in a swamp or woods.

When they got the green light from DPAA to mount a search at Stone’s suspected crash site on national forest land near Saint-Omer, the team was equipped with research and expertise across several academic disciplines. Volunteers like Tristan Krause ’18, Torrey Tiedeman x’20, and Samantha Zinnen ’19 would put their academic experiences in archaeology, anthropology, and history into practice during the mission. Gregg Jamison MS’06, PhD’17, a UW–Milwaukee at Waukesha anthropology professor, would be the scientific-recovery expert on site, directing a volunteer crew of UW–Madison students and staff, as well as anthropology students from Colorado College and volunteer veterans.

As in the Fazekas case, DPAA would be represented by lead forensic anthropologist William Belcher PhD’98, a professor of anthropology who brought one of his students from the University of Hawai‘i–West O‘ahu to the recovery.

After months of preparation, members of the UW–Madison MIA Project spent three weeks in the woods near Saint-Omer, carefully clearing trees and tons of earth from a site where, in 2017, DPAA investigators had found Walter Stone’s identification tag.

Using picks and shovels they carried into the forest every day, hauling dirt by buckets to sifting stations they built alongside the excavation site, the MIA Project group worked 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week. They recovered identifying parts of Stone’s plane — like .50 caliber machine guns, gnarled by the force and heat of the crash — along with the pilot’s remains and some of his personal items.

“So much happens before you even start digging. And then it’s just hard work. We were tired every day,” says Krause. “But to be able to do that for someone who sacrificed so much is an honor. It feels like the least you can do.”

“They Found Uncle Buster”

Mark Stone was on his way to the tractor supply store near Pensacola, Florida, in February when his father called and asked him if he was sitting down.

“He was so excited,” Stone recalls. “And he said, ‘They found Uncle Buster.’ I just couldn’t believe it.”

The Tablets of the Missing would be engraved with a rosette to mark the recovery, and Buster would finally come home to Andalusia. He was buried with military honors on May 11 — just days after what would have been his 100th birthday, and one day before Mother’s Day — in the family plot near the ever-hopeful Mama Stone.

“It means so much that there are people out there in this country — from Wisconsin, from the military — that would work so hard to do something like this, to do right by someone who served his country, and for his family,” says Mark Stone. “We owe them a lot. It makes us proud we’re all Americans.”

The Searchers

In summer 2018, University of Wisconsin–Madison photographer Bryce Richter journeyed to France to document the search for missing World War II pilot Walter “Buster” Stone. Along with capturing images of the UW’s MIA Project in action, he conducted video interviews with the hardworking team members. They explain their motivations for traveling halfway across the globe to honor a soldier who sacrificed his life for his country.