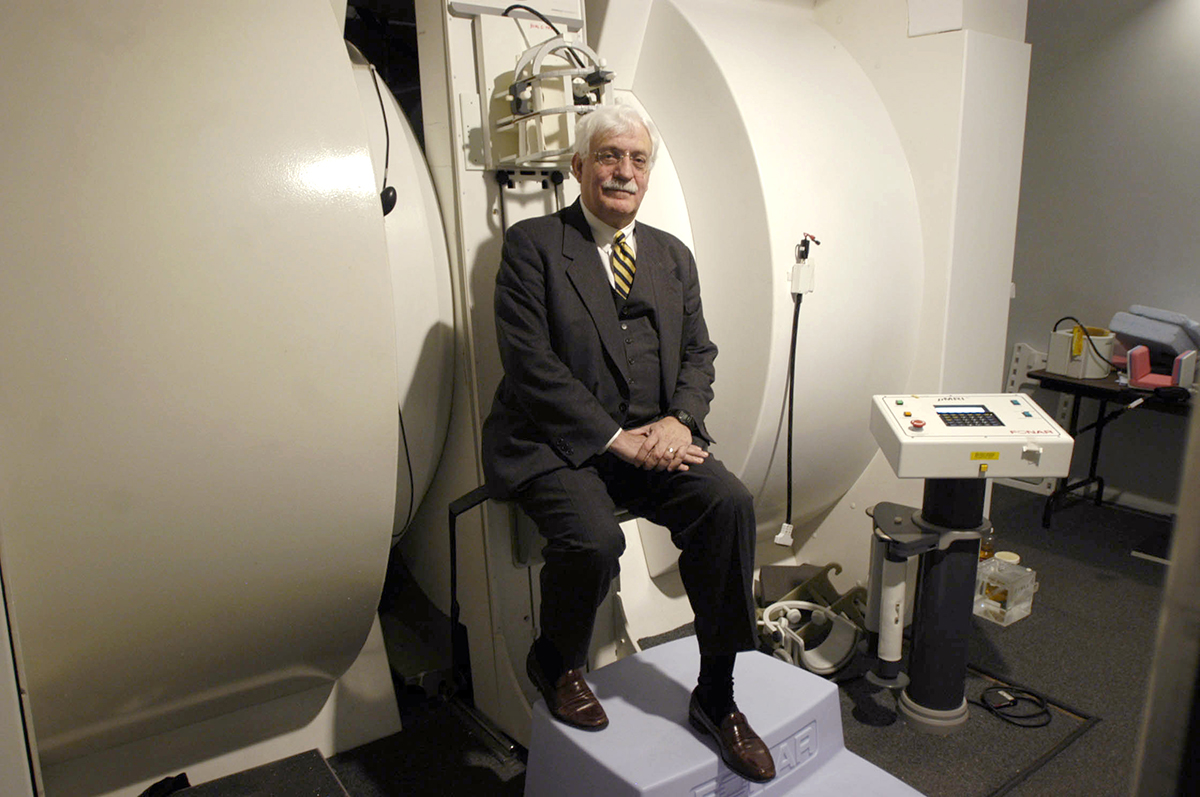

Father of the MRI

Raymond Damadian ’56’s discovery gave doctors more insight into their patients. Literally.

No scalpels required. Thanks to Raymond Damadian ’56’s remarkable invention, it’s no longer necessary to open up the human body to detect cancer or pinpoint an injury.

Damadian built the world’s first magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine and performed the first full-body scan in 1977, after he discovered that tumors and normal tissue emit response signals that differ in wavelength.

“I thought if we could do on a human what we just did in that test tube, maybe we could build a scanner that would go over the body to hunt down cancer. It was kind of preposterous,” Damadian admitted, “but I had hope.”

That initial scan of a colleague’s thorax took nearly five hours to complete in Damadian’s machine, which he dubbed Indomitable in a nod to achieving what many thought couldn’t be done. Indomitable now resides at the Smithsonian Institution.

Damadian took a unique path to making his contribution to the medical field. As a boy, he attended public school but studied violin at the Juilliard School on weekends. When he was 15, the Ford Foundation gave him a full scholarship to the University of Wisconsin, and he left Juilliard behind. “It was okay,” he said. “I was no Itzhak Perlman.”

But later in life, controversy swirled around him. Damadian wasn’t selected to win a 2003 Nobel Prize when two fellow scientists received recognition for their role in MRI development — and he didn’t take the snub lightly. In keeping with what has been called his “exuberant” personality, Damadian took out full-page ads in the New York Times and other newspapers with the headline, “The Shameful Wrong That Must Be Righted.” The scientific community was abuzz about this unprecedented step, taking sides about whether he deserved a Nobel.

“If I had not been born, would MRI have existed? I don’t think so,” he said.

His supporters believe that he was passed over for the prize in part because of his belief in creationism. A full explanation may come to light when the Nobel’s archives from 2003 are opened in 2053, though Damadian will never see it. He died in 2022. But the debate doesn’t matter to those experiencing pain or facing the possibility of cancer. Some 60 million MRI scans are performed each year, and patients are simply grateful for the machine that provides the answers.

Published in the Summer 2024 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.