Delicate Balance

As China gains prominence on the world stage, the university strengthens its connections.

Gilles Bousquet has a goal that he knows won’t make him popular among colleagues who teach French culture and literature: make China the number-one study-abroad destination for UW–Madison students.

“We want to prepare our students to be relevant, to be employable,” says Bousquet, the UW’s dean of international studies and vice provost for globalization.

The UW has China on the brain, as the country surges toward becoming the world’s largest economy. The university is seeking to boost the number of students who study Chinese language and are knowledgeable about Chinese culture by hiring more faculty with expertise in those areas. So far, about three hundred students are enrolled in Chinese language classes, and one professor specializes in Chinese history.

“All major American universities have some sort of presence here or are trying,” says Ed Gargan ’74, MA ’77, who has lived and worked in China for fifteen years as a book author and as a correspondent for the New York Times and Newsday. Harvard opened a center in a Shanghai skyscraper last year, and Stanford’s center at Peking University is under construction.

“English is taught to every urban Chinese pupil. [But] how many high schools, far less primary schools, in the U.S. teach Chinese? For the UW to be part of this rapidly changing world, it must engage China across a broad range of programs, departments, and schools,” Gargan says.

In coming years, the UW plans to explore ways to collaborate with a handful of top Chinese universities and is working on a proposal that would give the university a unique presence in the Shanghai area. This move comes as China makes massive investments in research and development, and in higher education — building world-class research facilities and wooing talent from around the globe.

“Do we see this as competition? Absolutely,” Bousquet says. “It’s also an incredible opportunity to partner. Right now, these institutions are in need of partners of the kind that Wisconsin is.”

UW delegations have made three trips to China in less than two years, and they are planning return trips every six months. Meanwhile, on campus, the UW has hosted a coach from Beijing Sport University and Chinese student-athletes who are Olympic- and world-champion medalists. The students study English, kinesiology, and sports management, and earn certificates through the Division of International Studies. They’ve been welcomed by Chinese families in Madison, played Ping-Pong with the Milwaukee Brewers, and — with eighty thousand people watching — have walked onto the field at Camp Randall Stadium at a Badger football game.

This Chinese Champions Program started when a Beijing Sport official asked Li-Li Ji MS’82, PhD’85, then a UW professor of kinesiology, for help with finding overseas experience for students pursuing master’s degrees in coaching, administration, and management. Ji, a native of China who is now at the University of Minnesota, recognized that bringing some of the country’s national heroes to the UW would be a “great gesture” toward expanding its relationship with China and attracting Chinese students.

And sports can be the best way to break down barriers, Ji says. “You are rivals on the field, and you’re friends off field. I think that the program symbolizes that relationship and provides some hope for both sides to see that our relationship could be as good as our athletes’ program.”

China: An Expert’s View

What kind of relationship does the United States have with China? The short answer: it’s complicated. Ed Friedman, a UW–Madison political science professor, was among the first researchers to enter China in 1978, as then-premier Deng Xiaoping began to open the country to the world. Friedman has returned dozens of times since then, and he is an expert on China’s politics and its people, including some who have become lasting friends. He recently sat down with On Wisconsin to share his perspectives on U.S.-China relations.

Cold War Allies

With the Soviet Union as a common enemy, the U.S. and China formed a cooperative relationship during the Cold War. The alliance helped then-President Richard Nixon win re-election, and it also restored some credibility for Chinese Communist party leader Mao Zedong in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, Friedman says.

Since the end of the Cold War, the two nations have shifted from allies to rival superpowers. “You lose the glue of a common enemy,” Friedman says. The Chinese government’s slaughter of hundreds of pro-democracy demonstrators on June 4, 1989, cast a pall on the relationship, and China’s authoritarian government came to see America as its biggest threat.

“America was the only country in the world, as China saw it, that stood up for democracy,” he says. “The thing the government fears the most is democratization.”

Rivals

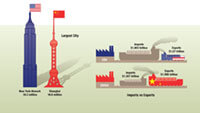

The United States didn’t begin to see China as a true rival until the 1990s, when its economy exploded and the nation began its meteoric rise to becoming the world’s largest exporter. Today, Friedman says China is increasingly assertive — and at times, anti-American — as it continues on a path to becoming the largest economy in the world.

While some politicians urge a tougher foreign-policy approach with China, the U.S. government has opted to hedge against worst-case scenarios. “One doesn’t want to act in a way where it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Friedman says. “That is, because you assume the worst-case things will occur, you act as if they must occur, and then you help make them inevitable.”

Although the Chinese government has continued to challenge President Barack Obama as he has reached out to the nation, his administration established a program to increase by 100,000 the number of Americans learning Chinese.

“You hope that you create mutual interests, so these bad things don’t occur, so people in Beijing will see that they don’t want worse to come to worst,” Friedman says.

Ship Building

China is aiming to be a superpower in every sense of the word. “They’re going to have a global military. They intend to be second to none,” Friedman says. “They are building aircraft carriers.”

China imports much of its energy, increasingly from the Middle East and Africa, and wants a blue-water navy to protect those resources and challenge what it sees as U.S. Navy dominance of international waters. “Once you build these kinds of capacities, they can be used for many different kinds of things,” Friedman says. “There’s every reason to think that as time goes on, you will see a Chinese military capable of challenging the American military all around the world.”

Different Treatment

China is not the only authoritarian government in the world — Friedman says North Korea, Sudan, and Syria are worse — but the United States treats it differently because of its economic might and military ambitions.

“The usual line from realists is, ‘The strong do what they will, the weak do what they must,’ ” Friedman says. That means the United States can’t pressure China on human rights and democracy as it would Cuba. If the U.S. government cuts off economic relations with China, it would ultimately hurt American employees working for major companies such as Airbus, Boeing, Motorola, Nokia, and Toyota.

“China is very conscious of that — it can play one against the other,” he says. “It has this huge economy in which it can do things like that. Other countries can’t do those kinds of things.”

Economic Realities

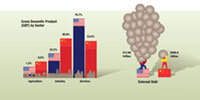

China has more than 1.3 billion people and has amassed more than $3 trillion in foreign-exchange reserves — money it can spend around the world to buy influence and support, Friedman says. Because bringing that money home would increase the price of its exports, China instead pours money into the U.S. economy, the source of the seemingly endless cheap capital that contributed to the current U.S. financial crisis. China’s currency manipulation — the yuan is considered to be undervalued by as much as 40 percent — maximizes jobs at home and keeps exports cheap, making it harder for the U.S. to increase exports and jobs.

“China is a major factor limiting our getting out of this great recession,” Friedman says. So why doesn’t the United States confront China on the issue and officially brand the country as a currency manipulator? To avoid triggering a trade war that could result in “something worse than the great recession,” he says.

But that doesn’t mean the question is settled.

“China doesn’t change its policies, and we are hurt, and unemployment remains at 9 percent,” Friedman says. “And at a certain point, unless you take on the Chinese on this manipulation of the currency, there’s a limit on what you can do for your own people. So how that plays out is a potentially extraordinarily explosive issue.”

No Democracy Now

Although protests against government corruption and cruelty take place daily throughout China, they are brutally suppressed or co-opted, and there’s no sign of the Communist regime losing power.

“I think this is the most dangerous illusion that Americans have — that somehow because it’s a dictatorship, it can’t survive,” Friedman says. “Most people in China, they may not love the regime, but they’re terrified that if they would try to change things, they’d get it worse.”

Britain was a world power in the nineteenth century while brutally exploiting workers, and the United States experienced rapid economic growth in the era of Jim Crow and a violent anti-labor movement. “You can have all sorts of horrors going on in society, and the state can still be stable and successful,” Friedman says.

China: The Student Experience

Twenty-two College of Engineering students spent six weeks in Hangzhou, China, in summer 2011, taking classes at Zhejiang University and touring the country. These excerpts represent blog entries they wrote about their experiences.

The Chinese students decided that we could make [dumplings] right in one of the dorm rooms, so we cleared off some space and got to work. I worked on mixing and kneading flour and water to make the dough, while others peeled and cleaned the celery, minced the pork, and chopped the celery. … It took quite some coaching from the Chinese students to teach us how to make the proper size piece of dough and the technique of how to fill the dumpling.

The dumplings were delicious, and their taste was only enhanced by that sense of pride you get after accomplishing a new and difficult task.

Mike Gionet x’13, nuclear engineering major from Mayville, Wisconsin

Making friends in China is as easy as snapping your fingers. Everyone seems eager to practice their English and take pictures. … I have become friends with two students from Zhejiang Sports College. Neither of them knows English and I have very limited skills in Chinese. To communicate, we rely on phone translators and hand gestures. It seems that the language barrier would make this relationship impossible, but surprisingly, few things are actually lost in translation.

Daniel Farley x’13, mechanical engineering major from Elkhorn, Wisconsin

The trip to Huangshan was a nice break from our class work and busy city life of Hangzhou. The natural beauty of the scenery makes it no surprise that every year millions of people travel here to vacation. None of this would be possible without the hard work of the porters who carry everything from food and water to building materials and fuel up the mountain.

These men use bamboo supports to hoist their loads before ascending the thousands of stairs to get to the top.

For all of their hard work, these men make very little money. … This is the first time in China I have been exposed to work conditions that shocked me.

Shawn Spannbauer x’12, mechanical engineering major from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin

Published in the Winter 2011 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.