Dance, Dance Revolutionary

Before she was a world-leading dancer, Mary Hinkson ’46, MS’47 learned to thrive in a segregated Madison.

“There are times when I believe ‘Bunny’ was born to dance,” said Cordelia Chew Hinkson of her daughter in a 1952 interview.

A year earlier, Bunny — as Mary Hinkson ’46, MS’47 was known to her family and close friends — had broken through the almost exclusively white world of modern dance when she earned a lead role with the Martha Graham Dance Company.

But if she was born to dance, she also learned — through her own effort and through her study at the UW. Between her youth and her debut with America’s leading modern dance troupe, Hinkson came to Madison, where she discovered the science of movement as well as some of the complicated realities of what it means to be black in America.

Hinkson was born to a storied African American family in Philadelphia on March 16, 1925. Her mother had been a public- school teacher, and her father, DeHaven Hinkson, was a prominent physician and the first African American to head a U.S. Army hospital. Hinkson’s aunt, Mary Saunders Patterson, was famed contralto Marian Anderson’s first music teacher.

A 17-year-old Hinkson arrived at the University of Wisconsin in February 1943. She chose the UW, in part, because it offered an extensive curriculum in physical education — the subject she aspired to teach. But Madison was far different from Philadelphia, and the transition wasn’t easy.

Although African Americans had matriculated at the UW since 1862, they were often excluded from white social events and faced ardent racism. An unwritten but widely acknowledged policy excluded African Americans from dormitories and most rooming houses. A 1942 survey conducted by the Daily Cardinal revealed that 95 percent of housemothers on the university’s list of approved rooming houses preferred not to rent rooms to black students. “Many Negro, and to a lesser degree Chinese and Jewish, students have been denied rooms that are vacant and have been forced into outlying districts or have been forced away from the university altogether,” the study noted.

Hinkson made arrangements to live off campus. Discriminatory housing policies coupled with the wartime economy — students were often displaced to accommodate military trainees — made securing campus housing nearly impossible. During her undergraduate years, Hinkson lived in the Groves Women’s Cooperative at 150 Langdon Street, where she shared a room with fellow dancer Matt Turney ’47. The interracial boarding house named for noted agricultural economics professor Harold Groves 1919, MA1920, PhD1927 brought together women from all over the world. Groves was Madison’s first women’s cooperative house, and it opened the year Hinkson arrived. Already well traveled, Hinkson likely thrived in the multicultural co-op, which provided vivid evidence that blacks could live with whites. Members worked together as part of a single household, cleaning floors and scrubbing toilets. Hinkson washed dishes and swept floors to defray the cost of lodging.

“World War II and its immediate aftermath led mid-century Americans to reconsider the nation’s democratic principles and the backdrop of unprecedented political, social, economic, and ideological changes,” Groves later recalled.

UW Dean of Women Louise Greeley wrote to President Clarence Dykstra in 1943: “We believe … that if a group of Negroes, Jews, and Gentiles such as this … can demonstrate ability to live successfully together, it will be worth trying.”

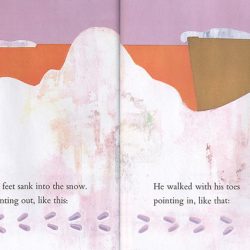

Hinkson dances in the Union Theater. Her experience with Margaret H’Doubler brought her to the attention of major dance troupes. UW Archives S16295

While at the university, Hinkson succeeded academically, earning mostly As and Bs, and she reveled in Madison’s robust dance scene, joining Orchesis, the UW’s modern dance troupe that had been founded in 1918. She studied English, French, history, zoology, and PE, and she impressed physical education professor Katherine Cronin with her “good mind and sincere attitude toward her work.” Hinkson soon changed her major to dance after taking a course with Margaret H’Doubler 1910, MA1924, and when she told her father of the change, he was reluctant but supportive. “If that’s what you want, go to it,” he said. And so she went: in 1945, she appeared in Orchesis’s production of Orpheus and Eurydice. The Baltimore Afro-American newspaper covered the performance, describing Hinkson and Turney as the group’s first “colored dancers.”

“[Mary] was in heaven,” her sister commented some years later.

Hinkson would long remember the remarkable teachers in the physical education department and courses with H’Doubler, a pioneer educator who had created the nation’s first academic program for the study of dance.

Though campus could be unwelcoming, Madison did attract African American artists and thinkers in the 1940s: anthropologist and choreographer Katherine Dunham and her dancers performed Tropical Revue at the Parkway Theater in 1944; Alain Locke was appointed visiting professor of philosophy in 1946; Pearl Primus and her “primitive modern dancers” appeared in 1948; and actor Paul Robeson was a regular feature at the Union Theater.

And Madison offered opportunities: it was at the UW that Hinkson was introduced to the Martha Graham Dance Company, which performed at the Union Theater in March 1946. H’Doubler had required her dance students to attend the show, and Hinkson said she was “completely blown away.”

Hinkson graduated in 1946 but continued with graduate courses. After a year of studies and writing a thesis, she earned a master’s degree and then became an instructor in the Department of Physical Education for Women — one of the first black women to teach at any majority-white university. Hinkson and three other students then formed the Wisconsin Dance Group, touring Toronto and across the Midwest in a 1933 Buick. The group included Turney, Miriam Cole ’46, and Sage Fuller Cowles ’47.

In 1951, Martha Graham asked Hinkson to perform a “demonstration” — a combination recital and audition. Graham then asked Hinkson to join her company, and by 1953, Hinkson held the title of principal dancer, starring in a production of Bluebeard’s Castle in New York. For 20 years, Hinkson was one of Graham’s leading dancers, and she also taught at the Juilliard School and at the Dance Theater of Harlem.

Hinkson may have found a challenging environment at the UW, but she left prepared for a key role in the world of dance. When she passed away on November 26, 2014, her obituary lauded her as “an influential teacher both in the United States and abroad,” “highly versatile,” and “one of Martha Graham’s most important leading dancers.”

During his library-science studies, Harvey Long MA’16 looked into the history of African American students on the UW campus. He now lives in Alabama.

Published in the Summer 2019 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.