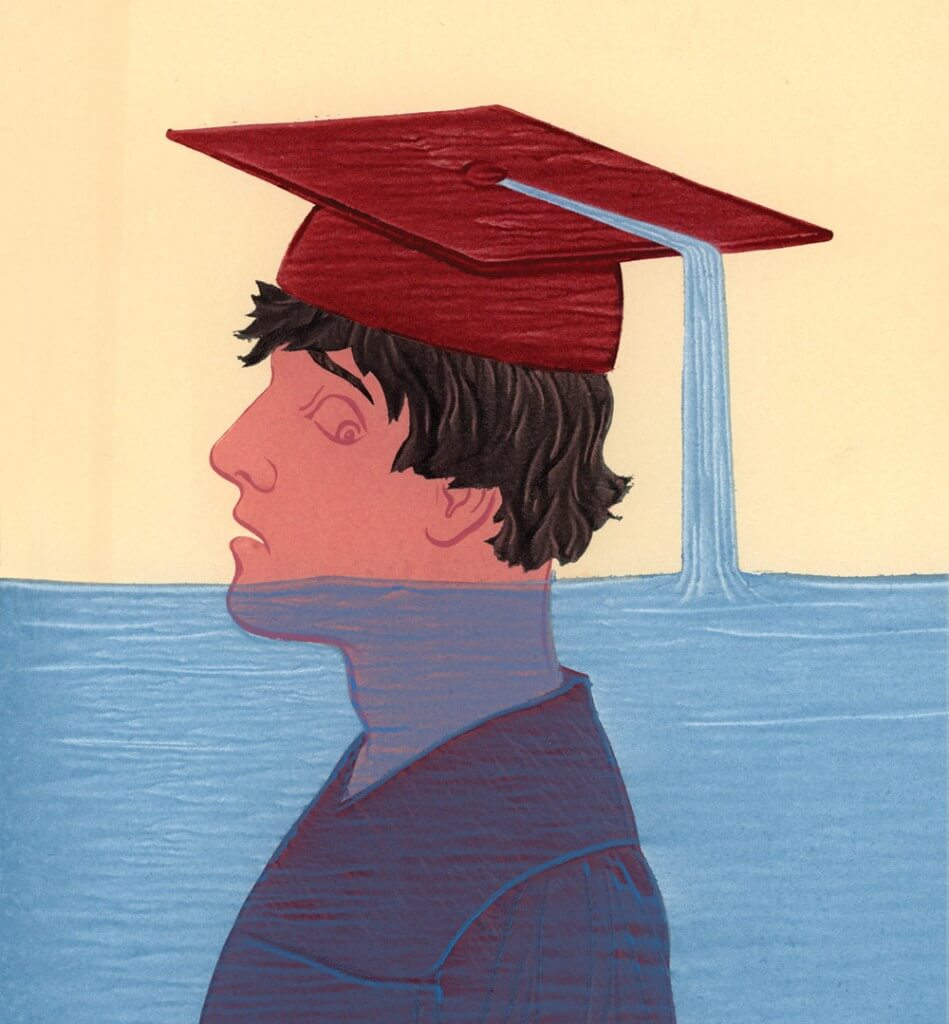

Are the Kids Really All Right?

As the cost of higher education increases, campus experts debate how to protect students from making disastrous choices — and explore whose responsibility it is to do so.

“This is insane.”

That’s what Susan Fischer ’73, ’79 told an out-of-state father when he called the UW–Madison Office of Student Financial Aid to discuss taking out a loan package totaling almost $160,000.

The response? “He said, ‘I appreciate your opinion, but our children want to go [to the UW], and we’re going to let them,’ ” says the office’s longtime director.

For the UW experts who study or work closely with student borrowers, discussions about debt usually lead to discussions with and about parents. After all, the current federal financial aid system is built on the assumption that parents will provide their college-aged children with at least some measure of financial support until age twenty-four. Yet for students who come from families less adept at financial decision-making, the existing student-loan structure can put them at a disadvantage.

A growing number of UW researchers are focused on developing a better understanding of the impact of indebtedness, both on the well-being of individual students and on the system of higher education as a whole. For example, School of Human Ecology Dean Soyeon Shim is overseeing the first longitudinal study of its kind to track the effect of financial literacy and indebtedness on young-adult well-being. And Nicholas Hillman, an assistant professor of educational leadership and policy analysis, is developing ethical frameworks for college financial-aid strategies and policy recommendations related to student loans.

The Value of a Plan

$8,413: that’s what it’s worth, on average, to have a plan for paying for college (vehicles such as 529s and ESAs, or Education Savings Accounts, which offer tax advantages and are intended to motivate families to set aside money for education). Families with a plan have an average of $18,518 in their student’s college fund; those without have $10,105.

From the Sallie Mae/Ipsos annual report “How America Pays for College.”

A student-debt doomsday?

According to the Project on Student Debt at the Institute for College Access and Success, seven out of ten college seniors nationwide graduated with some degree of student debt in 2012, the most recent data available. From 2008 to 2012, the average amount of debt increased about 6 percent each year.

Stories about the increasing level of student debt are often framed around the question of whether college is still “worth it” in terms of future earning potential. The answer, especially for those from lower-income families, is a definitive yes: according to the latest findings from the Pew Research Center, a bachelor’s degree still yields, on average, around 13 percent more in monthly earnings as compared to wages for those without a four-year degree. These earnings compound over a lifetime, as those with bachelor’s degrees can anticipate making almost double the amount of money earned by those with high-school diplomas, according to the U.S. Census. (See related story.)

Though there’s no denying the rate of student debt nationwide has increased overall, UW financial advisers argue that the scale isn’t as severe as it comes across in the headlines. “The ‘$1.3 trillion in student debt’ phrase [used in the media] is hyperbole. It’s so overblown,” says Fischer, adding that not all students borrow money for college and that the level of debt at a state university such as the UW isn’t the same as debt averages at private or for-profit colleges.

Some 50 percent of students at the UW have taken out loans, and the average debt load carried by students who borrow is $26,600. Michelle Curtis, the UW–Madison Office of Student Financial Aid associate director, is quick to point out that this dollar amount is on par with the cost of buying a new car or making a down payment on a house.

“There is no question that education pays off for people, and a modest amount of student loan to help you get that education is, I think, perfectly appropriate,” Curtis says. “And to not borrow and therefore not go to school doesn’t improve your future prospects.”

Shim’s research backs this up. She leads the Arizona Pathways to Life Success, a longitudinal study she began while on faculty at the University of Arizona. The study tracks the impact of financial literacy and debt on students from their freshman year of college through age forty. Shim says when it comes to a sense of personal fulfillment, the amount of money that young adults have in their bank accounts is less important than whether they perceive that money as sufficient for enabling independent, meaningful lives.

“We thought if you had debt, you would be unhappy,” she says. “But if it’s strategic debt, it’s not the debt that’s the bad guy.”

Essentially, Shim has found that college graduates are happier if they view money as a mechanism for self-fulfillment rather than looking at a specific net worth as the ultimate end goal. And while the result may sound simple, Shim believes it’s actually a difficult concept to convey effectively to young adults. Current financial-education strategies don’t fully prepare students for the choices they’re making in terms of managing debt or forging a sense of personal fulfillment.

“The message we’re telling the kids is [that money management] is for the future,” Shim says. “It has to be relevant to them and has to be about now, not just about the future. Really, you don’t save for the future. Those who save are happy right now. It’s what I call the positive psychological impact of saving on ‘present time.’ You have to be strategic about why and how much you save and why you need to borrow.”

Share the Load

Some 3 in 5 families believe that parents and students should share the responsibility for paying for college. Yet in 31 percent of families, the parents contribute no income, savings, or borrowed funds, and in another 31 percent, the student pays nothing out-of-pocket and borrows nothing. This leaves 38 percent of families in which both contribute. In contrast to the 20 percent of families who paid completely with out-of-pocket funds, some 20 percent of families saw parents increase their work hours to make college more affordable.

From the Sallie Mae/Ipsos annual report “How America Pays for College.”

“What kind of institution are you?”

Though education loans make real financial sense for many, the idea of debt can be a barrier. Experts say that capable students from lower-income backgrounds sometimes shy away from attending universities that will necessitate debt.

“Increasingly, large numbers of students are the first in their families to go to college and are not as comfortable taking out loans because there are some cultural norms about taking on debt,” says Hillman. As college-student populations become increasingly diverse, he adds, institutions will have to adjust their advising models to better resonate with students who are more or less comfortable with debt than were previous generations.

For an institution such as the UW, which is situated within a system of public schools that carry smaller price tags that attract lower-income students, debt aversion is having a real effect on the composition of the student population. “I think our campus suffers when we don’t have a broad socioeconomic class [representation],” says Fischer. “And I don’t think we do.”

It’s a scenario that doesn’t sit well with Miles Brown, a current undergraduate who is also a vocal advocate for student-debt reform and policy solutions, such as a bill recently proposed by Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren to allow students to refinance their education loans.

“If you’re [academically eligible] to go to a tougher school, you should be able to do that,” Brown says. “It’s a simple concept, and the mounting student-loan debt crisis really clouds it.”

For Hillman, the question of whether students with the ability to succeed have a right to a college education is a major one. “Education is a public good in the abstract,” he says. “I don’t think we talk about it enough. We don’t talk about privileges and inequalities and how we perpetuate them.”

Though it may seem like student loans are a new trend in higher education, Hillman says the federal government has been steadily moving institutions toward a loan-based system for the last forty years. “It’s been a steady shift from grants to loans, and now today we’re starting to see the implications of that shift,” he says.

Nationwide, about one in ten student-loan borrowers default within three years of graduation, the highest rate in about a decade. However, the vast majority of defaulters hold degrees from for-profit colleges, and Hillman says part of the reason why the UW’s rate of student loan default is low is that its students have strong employment prospects.

Previous studies measuring student default rates focused on student-level characteristics, such as GPA, socio-economic status, and race. “Lo and behold, a lot of low-income minority students had a high probability of defaulting on their loans,” says Hillman. “It really let colleges off the hook in a way. One study even said default is a pre-existing condition [for students from low-income minority backgrounds], and you should be thanking colleges for enrolling these students, giving them a shot.”

Yet institutional-level factors such as graduation rates and post-graduation employment statistics appear to be much more important. Hillman found that accounting for these factors made the student-level characteristics essentially disappear when it came to predicting default. “Whether a student earns a degree and finds a job, those are the biggest factors,” he says. “[So] what kind of institution are you? Do you truly value bringing up the students who have the most need?”

If institutional factors can negatively affect students’ post-college financial health, then it seems possible that some type of institution-based solution could also make a positive impact. The trick appears to be getting students to cooperate.

Buy the Book

$1,200: the amount that the College Board suggests college students should budget for textbooks every year. Some 40 percent of families report that textbooks cost more than they expected.

From the Sallie Mae/Ipsos annual report “How America Pays for College.”

Financial homework

Every student borrower can track his or her federal loans via the National Student Loan Data System, and UW advisers say it’s often an eye-opening experience for students to see the total amount of debt they’ve taken on, as well as their expected monthly payments after graduation.

Brown says he wishes more financial seminars or other workshops were available on campus to help him better understand the ramifications of his own loan decisions.

“I felt like I was at a significant disadvantage,” he says. “I wasn’t familiar with the concept of budgeting, and other things like that didn’t really cross my mind when choosing a university. It was pretty much up to me to do the whole college process on my own.”

Yet the team at the financial aid office has witnessed firsthand the gap between what students say they want and what they’ll actually show up for.

“We’ve tried doing workshops here, [and] we cannot get traffic,” says Fischer. “It doesn’t matter what you do. Students say, ‘If we can’t get credit for it, we won’t do it.’ There’s an irony of saying that for a financial literacy course, if you don’t have to pay for it, then you’re not going to take it.”

Shim, however, has decided to take students at their word. Faculty from the School of Human Ecology are developing a series of for-credit Financial Life Skills courses for the UW–Madison campus that could spread to other UW System schools.

“When we educate students about money, it isn’t just about money,” Shim says. “It’s about the role of money, how they feel about that, being able to plan ahead, and stick to their plans. These are very important factors in their success.”

Although undergraduates may, in theory, benefit from more financial education, the reality is that by the time student borrowers are checking the national database or taking a financial skills course, they’ve already signed up for thousands of dollars in loans. And though it’s likely that Brown is not alone in feeling like the loan information documents he received were confusing and unclear, the UW advisers say there’s ultimately only so much they can do when students just won’t read the contracts.

“There’s no substitute for parents sitting down with a student and saying, ‘Okay, let’s talk about what you just borrowed,’ ” Fischer says.

Fischer’s observations match Shim’s Pathways findings. Parental capability and involvement with financial decisions during college were by far the top factors that contributed to a young adult’s sense of financial well-being after graduation. Shim defines capability as, essentially, the capacity to learn financial information and to make positive decisions based on that information. It’s not a parent’s personal net worth that matters so much as his or her continued involvement in helping a student navigate financial choices during the college years.

However, financial parenting skills aren’t always as intuitive as one would think, as Shim learned firsthand during the early days of the Pathways project. The Shims had always planned to put their children through college themselves, but Shim began to doubt that approach after the first wave of data. Instead, she convinced her husband to read her research paper, and after much cajoling, he got on board with a new plan to make their daughter more personally accountable for her education.

The younger Shim was initially resistant to taking out a relatively modest loan and developing a plan to pay it back, but the result — according to her mother — is that she has become more mindful about her finances and is making more strategic career choices.

“I couldn’t buy that for her,” Shim says. “I’m so happy we did it. It’s been a life lesson for her.”

Not every student has an expert in consumer literacy or a director of financial aid as a parent. To help families with a lower level of financial savvy, the Pathways team is developing a set of recommendations to help parents guide their young-adult children through major financial decisions. Shim says the team is also working on ways to tailor these recommendations to fit different personality types, since no two young adults are exactly alike.

Advisers say they would love to see a willingness among parents to talk openly and honestly about the family’s financial situation, starting when a student is in the first years of high school. Several members of Fischer’s team say that during visits, it’s not uncommon for parents to ask students to leave the room when an adviser starts asking questions. Often, students have no idea that attending his or her “dream school” is causing a financial strain.

“They come home from the hospital in onesies with Bucky on them — that’s how far back this dream goes for some,” says UW student-aid adviser Todd Reck. “The problem is when you bring them home in the onesie, you’re not thinking, ‘Hey, I need to put a few dollars away in an account.’ ”

Great Expectations

Among American families with children under 18:

65% say that a college education is expected

51% are saving for college

41% have created a plan to pay for college

From the Sallie Mae/Ipsos annual report “How America Pays for College.”

Feeling down, but looking ahead

For Brown, advice about belt-tightening in college is unhelpful. “Our generation is dealing with something that previous generations couldn’t even imagine in terms of the cost of college,” he says. “To say that we need to work harder or not take out these loans is, honestly, insulting, because if they were in the same situation as us, they’d probably have to do the same things.”

According to data from Pathways, Brown’s feelings aren’t unusual. The majority of students experience a decline in psychological well-being immediately after graduating from college. “They realize life is tougher or a lot more serious than they thought,” Shim says.

Most, however, eventually experience a psychological rebound after landing a full-time job. In fact, Shim’s team has found that full-time employment affects young adult happiness more than debt. Those with a high level of debt who are working full time rate their satisfaction with life just as highly as those who are working with no debt at all. “It’s not the debt that matters. It’s that they feel self-sufficient,” she says.

For Hillman, student debt is an issue that hits particularly close to home. A former Pell grant recipient who carried an above-average debt load himself, Hillman worked three jobs and struggled to stay afloat during his undergraduate years at Indiana University.

“I was just overwhelmed. I thought it should not be this way just to [start] a career,” he says, adding that the only place he ever encountered other working-class students on campus was in the lobby of the financial-aid office.

“What keeps me going is that someday, I hope it will matter,” Hillman says. “I’m fighting the good fight — that’s what sustains me. We’re waiting for our window. Eventually these ideas will float through the right channels.”

Sandra Knisely ’09, MA’13, a news content strategist at University Communications, takes every financial seminar she can find.

Published in the Winter 2014 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.