All the World On Stage

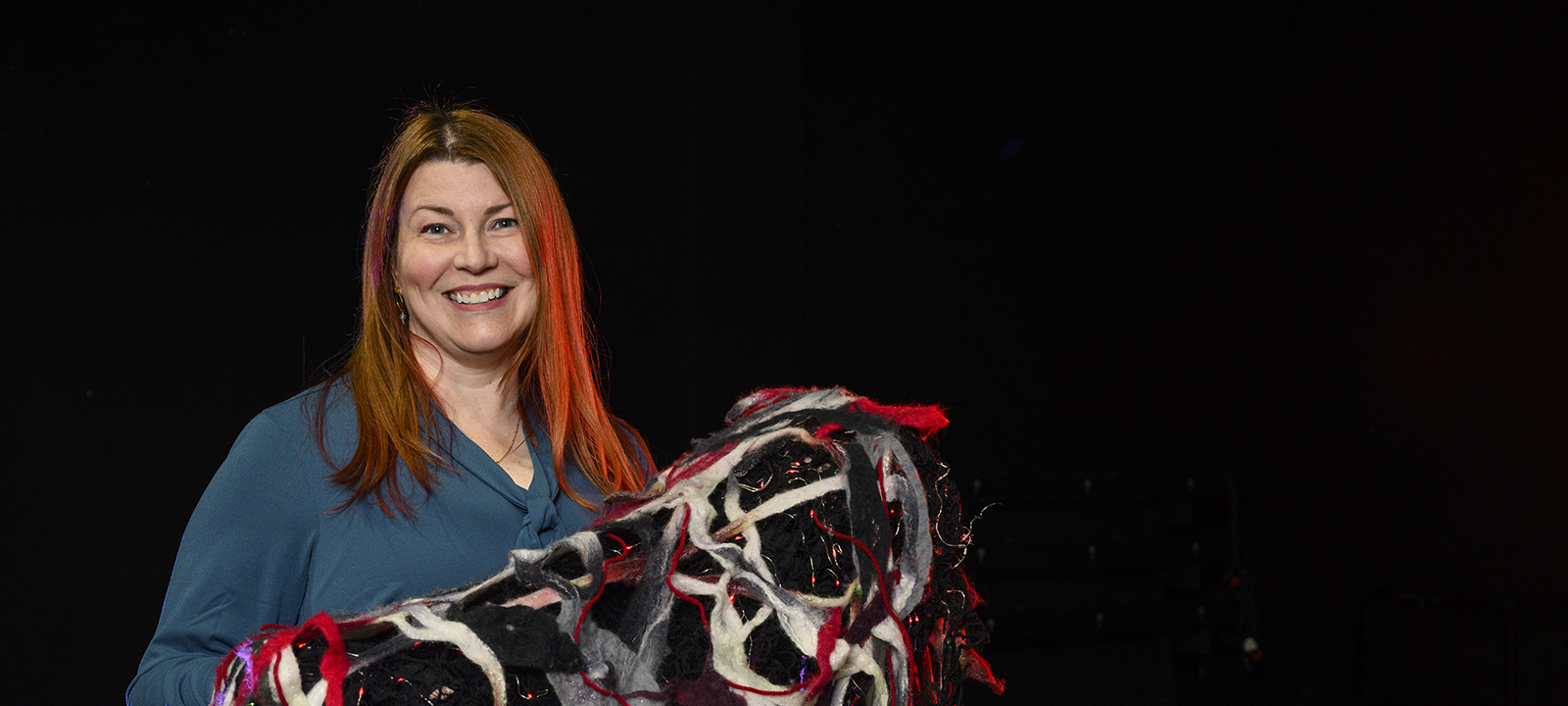

UW professor of design Aly Amidei creates costumes, characters, and a caring environment for performers.

Onstage costume changes guarantee oohs and aahs from audiences of live theater — think Cinderella’s bibbidi-bobbidi ballgown or the Into the Woods Witch’s return to youth. These quick changes aren’t as effortless as they’re made to appear, but Aly Amidei is adept at pulling them off — and on. After all, a quick change kickstarted her career in costume design.

Amidei is an assistant professor of design in the theater and drama department in the UW School of Education. A lifelong seamstress, she made her behind-the-scenes debut in her college costume shop while pursuing a degree in science — a path she swiftly abandoned in favor of a career in visual storytelling.

“Costume design was the perfect combo of the things that I liked about science — the creative problem-solving and the use of materials in new and interesting ways — with the things I liked about English, artmaking, drawing, and sewing,” Amidei says.

Throughout her three decades in the industry — as a designer, theater-company founder, and playwright — it grew clear to Amidei that traditional theatrical pedagogy often excluded individuals based on appearance or ability, barring aspiring artists from certain roles or from pursuing theater altogether.

Amidei has since dedicated her research to reimagining theater pedagogy to incorporate human-centered practices such as fair pay and humane working hours. This approach also extends to her costume design work, in which she prioritizes each performer’s identity and accessibility needs when composing their onstage appearance.

Shakespeare wrote that all the world’s a stage. Amidei wants the stage to look more like all the world.

How is costume design different from designing consumer fashion?

There’s a sustainability factor in theater costumes so that you’re making stuff that will last a long time — 40 to 60 years — so there’s a bit of an engineering angle to it. How do we make this so that it lasts forever or that it will work for multiple people in the future? It’s also the way that you’re telling stories. When you pick out your clothes in the morning, it’s just, “What makes me feel good? What will be appropriate for the things I have to do today?” But when you’re thinking about costuming a character, you’re considering how you’re telling this character’s story to the audience.

As a costumer, what unique perspectives do you have that might not be top of mind for an actor or a director?

There’s a lot of psychology around clothing that I think you pick up by paying attention to what people wear and why they’re wearing it — the codes and cues that clothing can tell an audience. Sometimes you send them one message, but that’s in opposition to what’s actually happening. I always use the example of American Psycho with Christian Bale: he looks very handsome, he is really well pulled together, but he’s going to kill you. We’re sending the audience cues that are different than what the actual character motivation is in that moment.

How do costumes help differentiate a familiar story across many productions?

One of the theater companies I work with a lot does adaptations of novels, so a lot of people have already read those books and have an imagination around what that character looks like. You are sometimes fighting that, even more so when it’s something that’s already been adapted to film. I use the example of Cinderella: when you do a children’s production of Cinderella, if you put her in anything other than a blue dress, children will flip tables and riot. Or, you purposefully subvert the expectations of the audience to tell them, “This is not your grandmother’s Cinderella. It’s going to be something different.” I generally try not to fight too much with expectations, but nod to them or play with them to tell the story.

How did your experiences in theater inspire the current focus of your research?

During one of my first experiences as a designer in college, one of my peers had a limb difference, so I was, from the get-go, thinking about how I could make this costume work for this actor. I was encountering that in my work, but not encountering it in teaching and what I was being taught.

How has your approach to costume design become more inclusive?

When I get a cast list, I usually try to get them for measurements. Now, I’ve updated that process to include a questionnaire where I ask them about access needs. I will ask things about what kind of clothing they like to wear. Do they typically dress masculine or feminine, or a mix, or no preference? If they wear special garments, I ask them to bring those to the first fitting. I ask if they have modesty needs: do you not want to show your arms? Do you wear a hijab? Do you have things like tattoos, but also do you have medical devices that you wear, like a prosthetic or a [colostomy] bag or an insulin monitor? … I’m trying to make it so that people normalize the sharing of these types of needs.

Comments

No comments posted yet.