A New Mission

For veterans who feel adrift upon returning home, Jake Wood has a suggestion: come along with us.

Jake Wood ’05 knew he would become a Marine the week that Pat Tillman died in Afghanistan. His decision was final. He discussed it with no one, not even his family.

Tillman was a former NFL player who left professional sports to enlist in the Army after 9/11. Wood was an offensive lineman for the Badgers who found himself filled with guilt for going to college and playing football while others were on the front lines.

In the four years following Wood’s graduation, he served tours in Iraq, where his unit did combat and ran counterinsurgency missions out of Camp Fallujah, and in Afghanistan, where he deployed after graduating from sniper school at the top of his class. He left the Marines as a decorated veteran and returned home to face another big decision: what’s next?

“I was a little apprehensive about taking off the uniform,” Wood says. “It was really that feeling that I was going to never do anything again in my life that was going to be so purposeful.”

When a massive earthquake hit Haiti in 2010, Wood made his choice: instead of sitting back and watching the devastation on television, he would go there to contribute the skills he learned in the military. Instead of going back to school to pursue an MBA as he had planned, he would serve. That moment was the origin of Team Rubicon, an organization that mobilizes volunteers to help in the hours, days, and weeks following earthquakes, floods, tsunamis, and other natural disasters.

Wood cofounded the group with William McNulty, a fellow Marine who signed on for the Haiti effort just minutes after Wood wrote a Facebook post looking for volunteers. The group has since deployed teams across the United States and around the world — from Burma to Chile to Pakistan. Team Rubicon now has twenty-seven thousand volunteers, most of them veterans, who help bring order to chaos following disasters and bridge the gap until conventional aid organizations can respond.

But Team Rubicon is also restoring something that veterans often lose when they take off their uniforms: it’s giving them a new mission.

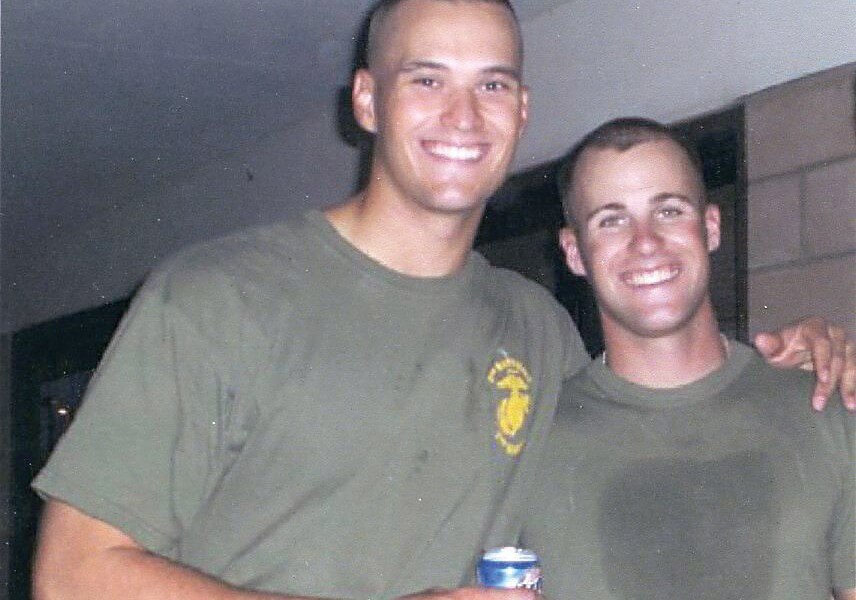

McNulty didn’t know Wood when the two connected ahead of their trip to Haiti, but he knew enough: Wood was a Marine. Once they met, he witnessed firsthand what he calls the six-foot-six Wood’s “command presence” — the effect of his natural charisma and gift for public speaking off the cuff.

“I’ve seen it where people are like, ‘You [want me to run] off a cliff? Okay, how fast do you want me to run?’ ” McNulty says.

Wood and McNulty are the frontmen for Team Rubicon, a sometimes uncomfortable position for people so strongly rooted in the concept of teamwork. As the organization’s profile has grown, the two are frequently asked about issues facing men and women after they leave the military. It’s not a role Wood says he feels qualified to take on as a “simple Marine sergeant,” but he is willing to share his perspective when asked how his group can help veterans make the transition from military service to civilian life.

“Some veterans are struggling. Why are they struggling? We believe it’s because they lack purpose and community in their life,” Wood says. “Other people might say it’s because of this chemical imbalance … Okay, that might be. You try giving him a pill; we’re going to try giving him a mission. At the end of the day, we’ll see which one works better.”

Wood makes it clear that Team Rubicon’s primary mission is providing aid following disasters, but that veterans are its fuel. They come from different generations and different wars and from all walks of life. Little outreach is needed: veterans find the organization mostly through word of mouth and social media. David Dodds joined the team in 2012 after reading a friend’s social media post. He knows veterans who have struggled with their return to civilian life. “They feel kind of useless,” says Dodds, a defense contractor and Army veteran who served two tours in Afghanistan and Iraq. He volunteered on a number of projects for Team Rubicon and now serves as the group’s operations coordinator in Virginia.

For Dodds, the involvement is personal: one of his friends took his own life in summer 2014. He also knows a veteran who considered suicide, but found a new purpose through Team Rubicon. “Stopping that from happening is huge,” he says.

During its inaugural mission in Haiti, the small team of volunteers sat in a circle and drank Dominican beer after a long day providing medical aid at a displaced persons camp. Brother Jim Boynton, a Jesuit schoolteacher working with the volunteers, encouraged them to talk about what they had seen and done during the hours before. Wood had cleaned dirt, gravel, and pus from an infected wound in the leg of a young boy as he screamed in pain. Other team members had performed amputations and one had delivered a baby.

One by one, team members — including Wood — shared their experiences. “There was this boy today …” he began. These kinds of conversations take place around a fire or in the church basements or school gymnasiums where volunteers gather at the end of each grueling day. Images of devastation can bring back wartime memories, but the shared physical labor breaks down barriers. “They feel comfort and trust for the first time in a while,” Wood says. “You’ll see people who will start talking about their experiences either in the military or postmilitary, and they’ll end their story with, ‘That’s the first time I’ve ever told anyone out loud.’ ”

Civilians are often afraid to ask veterans about their experiences overseas, worried about offending them or bringing up bad memories, even though most veterans look back on their service as a great time in their lives, Wood says.

“Somewhere along the line, we lost this community focus, [this] community-centric approach to veteran reintegration,” he says. “I don’t know why that is.”

But victims of natural disasters quickly learn the value of welcoming veterans back into their communities, Wood says. “These homeowners say, ‘Wow, I’m so impressed, I feel like this is the best America has to offer, and I never would have known it,’ ” he says.

“Ultimately, the analogy I’ve been using is that we see Team Rubicon over the next five years becoming, in essence, a national volunteer fire department.”

Donna Burdett was an EMT and nurse by age seventeen, joined the Navy as soon as she was old enough, and hoped to become a doctor. An explosion during the first Gulf War left her with a brain injury, and her dream disappeared. After multiple surgeries and procedures, she retired from the Navy. “I felt thrown away by the world,” she wrote in a blog post earlier this year.

After spotting an online ad for Team Rubicon, she signed up to deploy following an ice storm in Georgia in February 2014, but feared her injuries would ultimately lead to rejection. Then the phone rang. “We would like you to come help us,” a volunteer coordinator said. She has since signed on for other team missions, and says that participating is like being in the Navy again.

“I’m no longer broken,” she wrote.

Sharing stories is part of the team’s culture. Wood urges volunteers to talk to the public and the media about themselves and how they came to be part of the group. “I started as just a pipsqueak freshman at the University of Wisconsin. Somehow I ended up in Iraq and Afghanistan. Somehow I ended up in Haiti,” he says. “But that’s the unique story that brought me to Team Rubicon, and every- body else has one of those.”

Progress was often elusive on the ground in Iraq and Afghanistan, says McNulty, who worked in intelligence. Now as some veterans watch ISIS and other destabilizing forces surge in those regions, they wonder whether the sacrifices were worth it. “[But] when you’re clearing the mud out of someone’s basement after a flood just struck, or you’re bandaging someone after they were injured because of the high winds of a typhoon, you can see the fruits of your labor,” he says.

Fewer than thirty-six hours after a 7.8-magnitude earthquake hit Nepal in April, killing thousands and leaving survivors in remote villages without aid or medical care, Team Rubicon launched Operation Tenzing. A small reconnaissance team traveled to Kathmandu and partnered with a startup U.S. drone company to obtain aerial images that would help assess damage and update maps of the disaster zone. That quick and thorough groundwork — core to the experience of veterans — allowed Team Rubicon to pinpoint areas with the greatest need for help and deploy teams to dispense medical aid, food, and water.

In a video taken during that first mission in Haiti, Clay Hunt rides through the streets of Port-au-Prince in the back of a beat-up pickup truck, surveying the devastation. “I’m here because I’m needed here,” he says.

Hunt and Wood were like brothers after serving together in Iraq and Afghanistan. Hunt was deeply affected by the loss of Marines in their unit on both deployments, and he struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder. A year after the Haiti mission, Hunt took his own life. He was twenty-eight years old. An estimated twenty-two veterans do the same thing each day, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

A year after Hunt’s suicide, Wood told 60 Minutes that he wonders almost every day why it happened. He sometimes blames himself. Last February, Wood stood in the East Room of the White House as President Barack Obama signed the Clay Hunt Suicide Prevention for American Veterans Act, intended to reduce military and veteran suicides and improve access to quality mental health care.

“Clay has taken on this almost mythical status within Team Rubicon,” Wood says during our interview. “When Clay passed, we had three hundred, four hundred, maybe five hundred volunteers in the organization, and only thirty of them had ever met Clay. And so now we have twenty-seven thousand members — and still only thirty of them have ever met Clay. At the end of the day, what’s powerful about Clay is that he was just a guy.”

Hunt’s legacy serves as a reminder that although disaster relief is Team Rubicon’s business, veterans are its passion. In 2014, it launched the Clay Hunt Fellows Program, which provides leadership training for a small group of veteran volunteers. Each fellow receives a $12,000 stipend and must undertake a capstone project that improves the organization. The goal is to develop leaders within the team, as well as help its veteran volunteers compete and thrive in the civilian job market.

Wood says it is an opportunity Hunt would have liked.

How Team Rubicon got its name

The organization’s name references the days of Julius Caesar, who famously crossed the Rubicon, a river in northeastern Italy, to march on Rome and never looked back. In January 2010, Jake Wood and a small group of volunteers traversed a river border between the Dominican Republic and Haiti to bring aid to thousands of earthquake victims in camps — a journey considered too dangerous by other aid organizations. They decided that moment was their Rubicon, and they, too, were irrevocably committed to their mission.

Team Rubicon had already proved its worth to veterans. Now it needed to show the American public what it could do. When Hurricane Sandy hit the Northeast in fall 2012, the group took a chance to solidify its reputation among disaster-response experts. Money was tight, but team leaders made the decision to put “all our financial chips on the table,” Wood says.

More than 350 Team Rubicon volunteers from across the country descended on New York and New Jersey and led ten-thousand-plus volunteers who helped in every possible way — pumping sand out of homes, clearing dangerous debris, and patching roofs.

“It was a make-or-break moment for us,” Wood says. “Everybody in the U.S. — from every news agency to every federal agency — was looking at that fifty-square-mile area. And we had an opportunity to show these people who hadn’t paid attention to us for two and a half years what we were doing and what we were capable of.”

The gamble paid off. Goldman Sachs donated $250,000 to Team Rubicon for Hurricane Sandy operations. Other corporate sponsors followed. Wood was approached about writing a book on leadership. (The result was Take Command: Lessons in Leadership: How to Be a First Responder in Business, published in 2014.) Most important, the effort, dubbed Operation Greased Lightning, solidified the group’s credibility in disaster response.

“[The Federal Emergency Management Agency] came out and was blown away by what we were doing in the far Rockaways,” Wood says.

This year, McNulty is leading the launch of Team Rubicon Global, building a presence in Australia, Canada, Norway, and the United Kingdom — all key U.S. allies in Iraq and Afghanistan. A five-year plan calls for twelve teams around the world, each offering veterans the same opportunity to serve as their American counterparts and the ability to respond more quickly to disasters.

But the work on the home front is far from finished. Team Rubicon is hiring ten regional administrators, intending to have staffing at the state level in ten to fifteen years. “Ultimately, the analogy I’ve begun using is that we see Team Rubicon over the next five years becoming, in essence, a national volunteer fire department,” Wood says. “Obviously we don’t fight fires.”

Wood doesn’t get out into the field as much as he did in the early days, but he makes sure to do so at least once a year to challenge his assumptions about how the organization is evolving and to reconnect with its core mission. “At the end of the day, I need to go out there and swing a sledgehammer and help people as much as anybody else,” he says. But now, as chief executive officer, he devotes significant time to giving speeches and fundraising — and numbers play a far more critical role in his life than he could have predicted during his student days.

“People who want to be entrepreneurs ask me that question all the time: ‘What’s the most important class?’ ” he says. His response? “Basic accounting principles.”

In his book, Wood describes the importance of being surrounded by people who buy into a shared vision. Team Rubicon wants “people who are foolish enough to think they can change the world — and smart enough to have a chance,” he says during our interview. “We’ve been saying that we can build an organization that’ll disrupt industries and be around for the next 150 years. We’re not just saying it to hear ourselves say it. We’re saying it because, goddamn, that’s what we’re going to do.”

Jenny Price is senior writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Fall 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.