A Museum’s Greatest Hits

A critical look at the Chazen’s most significant works of art.

There are 24,299 pieces in the collection of the Chazen Museum of Art. The oldest object is a relief fragment from the tomb of Ptahhotep II at Saqqara, which is about 4,300 years old. One of the newest is Distorted Nude Photogravure #4, a 2021 image by David Lynch (yes, the Twin Peaks David Lynch).

As with most museums, only a fraction of the collection is in the public galleries at one time. Even with 1,000 pieces on display, it’s a lot to take in. If you limited your interaction with each one to a one-minute perusal and a meditative “Hmmm, interesting,” you’d be wandering the galleries for nearly 17 hours — not including bathroom breaks and a trip to the gift shop.

If wandering is your thing, go for it. This isn’t the Louvre, where you have to elbow your way through the crowds to glimpse the Mona Lisa. It’s a manageable collection, great for an afternoon meander or a more focused visit on a lunch break. But it still presents a somewhat daunting question: what are the highlights, the must-sees, the handful of pieces that are guaranteed to stick with you after your visit?

To find out, I spent time with the people responsible for assembling, organizing, and displaying the collection. Their suggestions are a great starting point for any visit to the museum or its excellent website, where you can see images of every item in the collection. Their choices also speak to the Chazen’s big picture: where it’s been, where it’s going, and how it fits into the university and Madison communities.

A Spectrum of Civilizations

To get a nutshell idea of the Chazen’s scope and mission, just step inside the Mead Witter Lobby and look around — all around. The soaring, three-story space is architecturally clean but aglow with the sheen of cappuccino-colored marble. Look up the monumental staircase on one side of the room, and you’ll see the entrance to the galleries. Opposite that, behind a two-story sheet of glass, is the adjoining Elvehjem Building, the original UW art center that opened in 1970.

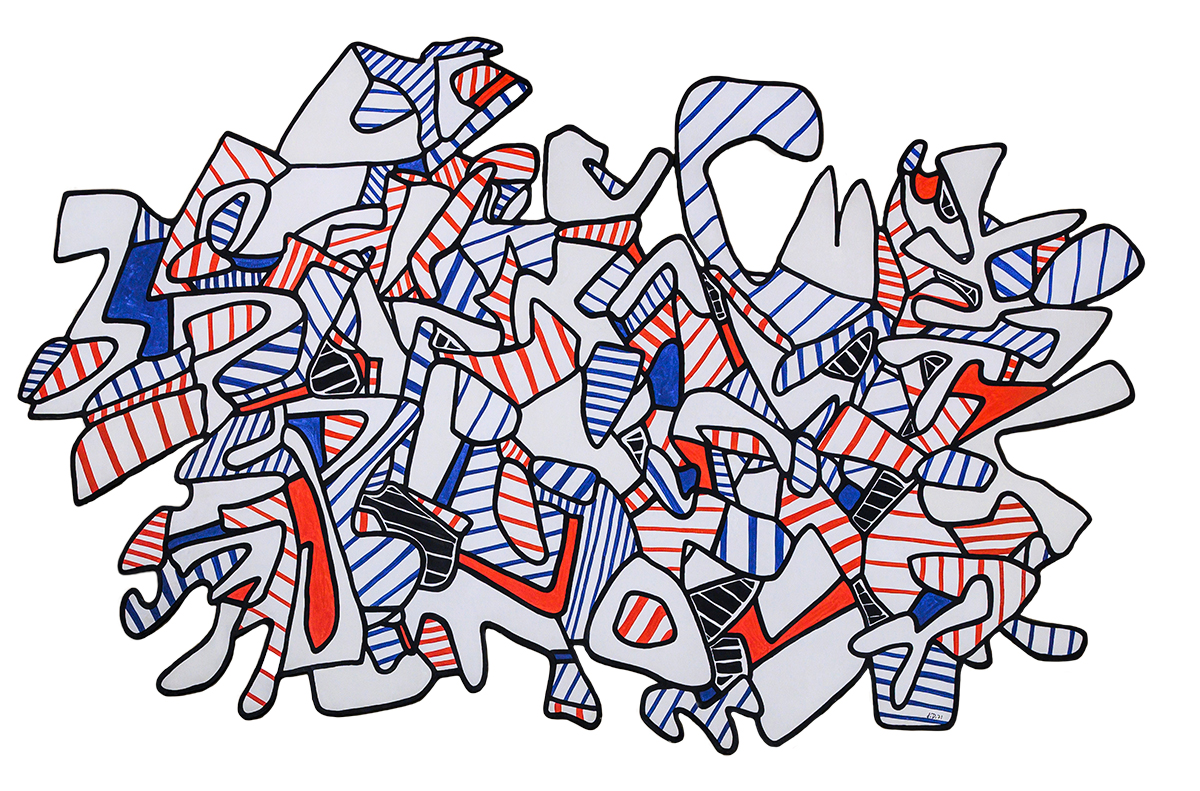

Hovering over that staircase is Jean Dubuffet’s massive Danse Élance (1971), which blazes in primary colors and bold geometry against the interior’s golden walls. Next to you, on ground level, is Mary Sibande’s monumental bronze sculpture Sower in the Field (2015), one of the first pieces acquired under the museum’s Contemporary African Art Initiative.

Danse Élance

Jean Dubuffet (French, 1901–85)

Primary colors and bold geometry blaze in the Chazen’s lobby.

The newcomers to the atrium — moved here from the Elvehjem Building during a renovation — are harder to spot. Down the hallway toward the elevator, a wall display highlights Greek pottery from the sixth century BCE.

This is the Chazen today: ancient, modern, contemporary. Painting, sculpture, decorative arts. Abstract and figurative. A spectrum of civilizations — the museum covers a lot of cultural and aesthetic territory.

That’s no surprise considering the Chazen’s mission. “It’s an academic museum and it’s a civic museum,” says director Amy Gilman. “Because of our physical location, we are right on the border between the campus and the city. In fact, we face both directions, and I like to lean into that.”

Sower in the Field is at the center of that intersection, representing the Chazen’s forward-looking approach to African art. “The traditional way of seeing African art is that it’s fixed in time — the time when the country was colonized,” explains Gilman. “Of course, that’s not accurate. There’s a vital contemporary art scene across the continent. The Sibande is an important part of diversifying our collection and developing a strength in contemporary African art.”

And that feeds into programs at the university. “The UW has a long history of African studies in many different departments,” she says. “It’s a great way for us to connect different parts of the university to each other and to the Chazen.”

But how do you connect to the Chazen? Here’s a curated introduction to some of the museum’s most significant pieces.

Iskwaaj Nibi (The Last Waterhole: Creating a New World)

Rabbett Before Horses Strickland (American, Ojibwe)

A radiant palette illustrates the lore of the Anishinaabe people.

Tangible and Timeless

Iskwaaj Nibi (The Last Waterhole: Creating a New World) is a luminous 2018 painting by the Ojibwe artist Rabbett Before Horses Strickland. Inspired by the mythological paintings of Peter Paul Rubens and Sandro Botticelli, Strickland uses a radiant palette and bustling compositions to illustrate the origin stories and lore of the Anishinaabe people of the upper Midwest.

Like the Renaissance art that informs it, Strickland’s work is epic in scope but filled with enigmatic details that are potently symbolic. Human figures, spiritual beings, and an assortment of carefully rendered flowers and wildlife share a mythological space that is both tangible and timeless. PBS Wisconsin commissioned the painting in conjunction with a documentary about the artist and donated it to the museum last year.

Adoration of the Shepherds

Giorgio Vasari (Italian, 1511–74)

Stylized gestures showcase Vasari’s skill in painting the human figure.

A Massive Altarpiece

As an admirer of Botticelli, Strickland would undoubtedly be drawn to Giorgio Vasari’s Adoration of the Shepherds. Vasari literally wrote the book on Botticelli, or at least included him in a chapter of his iconic collection, The Lives of the Artists. He wrote gossipy biographies of hundreds of Italian artists: “Every art history student reads them,” says chief curator Katherine Alcauskas with a grin, “and they are really catty.” He was also a practicing painter and architect (and therefore maybe not the most objective biographer).

Adoration of the Shepherds is a massive altarpiece originally painted for the church of Santo Stefano in Pane in Florence, Italy, in 1570–71. The record of its ownership is a long and serpentine tale, which includes Chicago financier Charles Yerkes, a major force behind Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, but it eventually came to UW–Madison in 1923. It was the collection centerpiece when the Elvehjem Art Center opened and was recently moved to a specially designed room at the Chazen, no easy undertaking for a work almost 11 feet high and painted on a nearly two-inch-thick wood panel. “Often when big altarpieces came to America by ship,” says Alcauskas, “they would plane down the panel to make it thinner and lighter. Not this one.”

The move into its new room was almost as complicated. “It had been in the same location at the Elvehjem since it opened,” says Gilman. “We had to figure out how to get it off the wall because no one who hung it was still around.”

But it was worth it. Alcauskas calls the painting an exemplar of its Renaissance era. “It’s in the mannerist style,” she says. “The palette is in pinks and greens rather than reds and blues, and the figures are contorted in stylized gestures to showcase the artist’s skill in painting the human figure.”

In its new Chazen home, the painting is surrounded by rich blue walls and is flanked by a pair of less monumental works by 17th-century artists that depict a similar scene — the adoration of Jesus following his birth. These paintings are darker, their tableaux less animated, and they highlight the distinctive colors and style of Vasari’s work.

Bad Bunny

Centuries — and worlds — away from the solemn reverence of the Vasari is Beth Cavener’s playfully sinister sculpture, L’Amante (2012). Given pride of place in the center of a large contemporary gallery, it’s one of the most popular pieces in the collection. “Cavener sculpts animals, but they are modeled on people she knows,” Alcauskas explains. “She’s exploring the animalistic nature deep inside us: our fight or flight response and our primal nature.”

There’s no fight or flight in L’Amante, however. Cavener’s rabbit poses languorously and somewhat defiantly, as if it’s daring you to challenge its dark supremacy. Look closely, and you’ll see the sculpture is covered in faint tattoos, reminiscent of those found on Yakuza foot soldiers. You don’t want to mess with this bunny.

Organic and Otherworldly

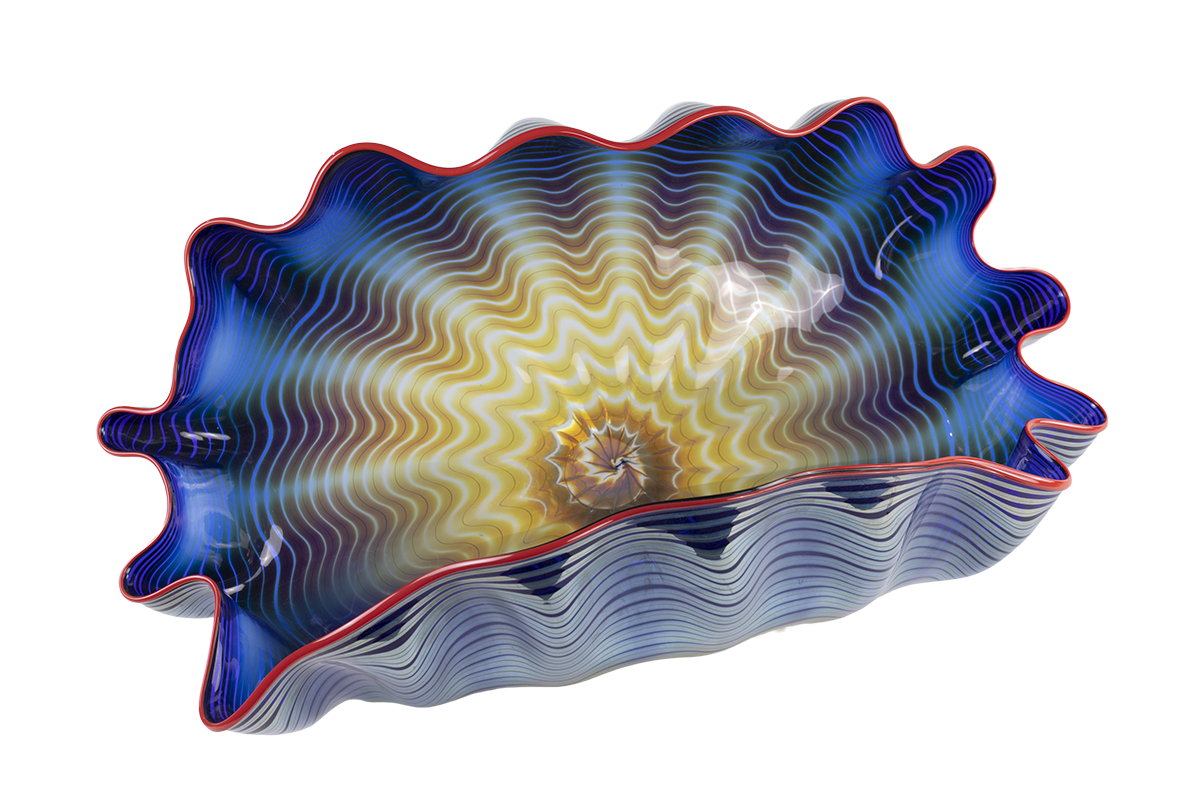

If Cavener has you a little chilled, bask in the glow of Dale Chihuly MS’67’s Blue Persian with Red Lip Wrap (1999). Chihuly is one of the most recognizable sculptors in the world, and his glass pieces are permanently installed in dozens of public spaces and museums, including his 140-foot Mendota Wall in the north lobby of the UW’s Kohl Center. His presence at UW–Madison is appropriate: he studied on campus with Harvey Littleton, the first person in America to teach studio glassblowing in a classroom setting.

Blue Persian with Red Lip Wrap

Dale Chihuly (American, b. 1941)

The undulating surface transforms Chihuly’s spiral of color.

Part of his “Persian” series, this piece shows Chihuly’s ongoing fascination with the properties of glass. “It’s from a period in which he started experimenting with gravity and the almost accidental way that nature can form the pieces,” explains Alcauskas. “Here, he’s borrowing techniques from several cultures and time periods, mixing old and new. He’s blowing glass into a mold as they did in the Roman Empire in the first century CE. The red tint around the rim demonstrates the use of caning, also a technique practiced in the ancient Roman Empire.”

It isn’t one of Chihuly’s spectacular chandeliers, but the smaller scale allows you to absorb the variety of details: the way the undulating surface transforms the spiral of color, and the way cool geometry and supple contours combine in a single object that is both organic and otherworldly.

Inside Picasso’s Head

Form is also of the essence in the modernist sculptures in the Terese and Alvin S. Lane Collection, including works by masters such as Louise Nevelson, Alexander Calder, and David Smith. But the real treat in this collection is the display of small sculptures alongside the sketches that informed them. Alvin Lane ’40 was interested in what he called the “tangible evidence of creativity” — the signs of the artist’s imagination at work.

The journey from idea to execution is wonderfully displayed in three pieces by Pablo Picasso, including two studies and the finished work Standing Woman (Femme debout) (1961). Side by side, you’ll see a sketch on a sheet of paper, a cardboard model that expands on it, and the final product — a full figure crafted from a sheet of steel.

“The three objects really demonstrate the way that one artist approaches the creative process,” says Alcauskas, emphasizing how pieces like these are important to the Chazen as a teaching museum, where students can chart the evolution of an artist’s work. “You can see how he has changed the way the arms project out and how he finessed the exact angle of some of the elements to make a kind of Cubist face.”

Examining the pieces side by side, you can see Picasso’s attention to detail and, in a way, spend time inside his head while he crafts his work.

Seeing the World Differently

Of course, every piece in the museum’s collection offers a similar glimpse into the artist’s process. Why this color here? Why crop the photo there? Why this curve or that hard edge? These few pieces are just a start, but they offer an entryway to the Chazen’s value and richness.

“Visual art is a great way of making you see familiar things in unfamiliar ways,” says Gilman, summing up the significance of the collection, “and then seeing the world differently.”

That’s true whether we’re students, seeking to develop our own way of seeing and creating, or just admiring observers who want to surround ourselves with beauty. •

Paul Kosidowski MA’86 is a Milwaukee-based writer and arts critic. He spent many a pleasant afternoon wandering the Elvehjem Museum during his student years.

Published in the Fall 2023 issue

Comments

Cindy Brenard July 31, 2024

The museum offers something for everyone, even the little artists! The building itself is a work of art. Thank you so much for offering the marvelous collections which spans the time of 500 b.c. to present day! (I hope I’m close to being correct about the dates.)