A High-Fat Diet That Heals

For stubborn seizure disorders, an unorthodox prescription brings relief.

As Elizabeth Felton visits with her patients at UW Health’s newest facility on Madison’s east side, the delicious aroma of their prescription fills the air: the smoky tang of frying bacon and the savory fragrance of rosemary-onion dinner rolls just out of the oven.

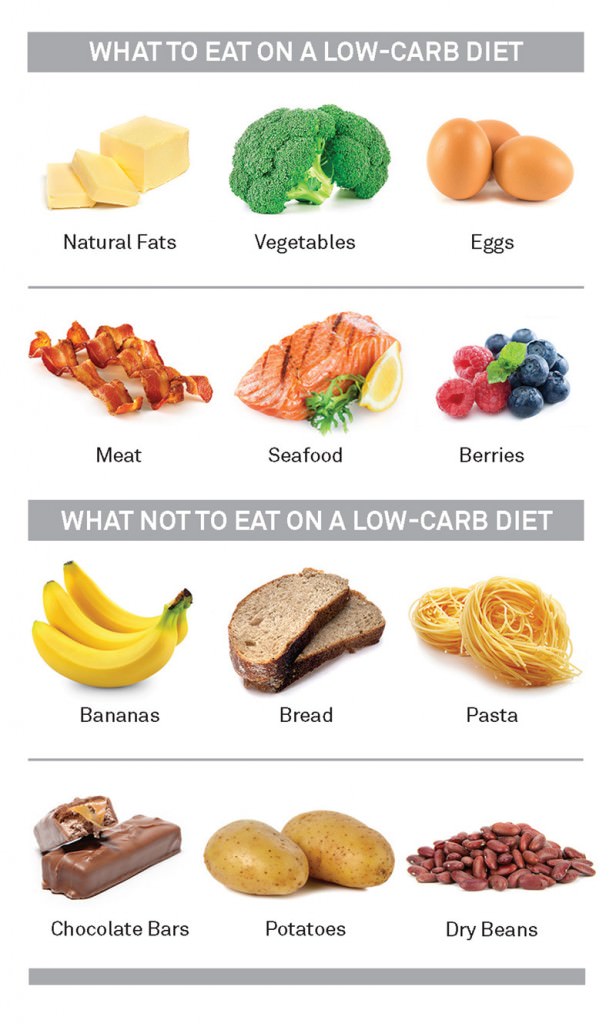

Turkey and mashed cauliflower are also on the holiday menu, made up of recipes for a feast that contains just 10 grams of carbohydrates per diner. The rest of us will gobble hundreds of grams of carbohydrates on Thanksgiving, but these chefs have epilepsy. And they come to UW Health’s Learning Kitchen from as far away as Iowa and Michigan to learn how to prepare a high-fat, low-carb diet that might control their seizures.

Longtime readers of On Wisconsin may remember the story of young Charlie Abrahams, who appeared in our pages more than two decades ago, grinning over a plate of bacon and eggs. His father, Hollywood writer and producer Jim Abrahams x’66, had recently established a foundation in Charlie’s name to spread the word about the ketogenic diet that cured his son’s intractable seizures. Twenty-two years later, the diet has spread as far as India and Brazil, and it’s found a home back at UW–Madison.

Today Charlie is doing well. Five years on the diet cured his seizures, as it does for about 20 percent of children who try it, and afterward he was able to resume a normal diet. He’s now a community-college graduate and working as a teacher in California. He barely remembers being on the diet as a preschooler, and he has no memories of the years his parents had to strap him into a car seat for protection because he had up to 50 seizures a day.

While Jim Abrahams still does script-doctoring in Hollywood, the Charlie Foundation for Ketogenic Therapies has become his life’s work — and a global force in promoting the diet.

“I really thought I’d be doing this for a year, and then once people found out that there is an alternative to taking all those drugs, it would be mainstream,” says Abrahams. But hurdles remain. Some neurologists don’t recommend the diet, which consists of 90 percent fat, because they believe it is too difficult for patients to maintain. There’s also a shortage of dietitians trained in the subject, and it can be difficult to get insurance companies to reimburse for appointments.

But there’s also been progress since the 1990s, when one of the last people who knew much about the diet was a Baltimore dietitian on the verge of retirement. The diet was known to control seizures by forcing the body to burn fat rather than carbohydrates, a metabolic process producing ketosis. But with the development of antiseizure drugs, it had all but died out.

Flash forward to September 2016, when more than 600 physicians, researchers, and nutritionists from 32 countries gathered in Banff, Alberta, to share their research on the diet’s potential for controlling epilepsy and treating brain ailments ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to cancer.

The group included nutritionist Beth Zupec-Kania ’81, whose career was dramatically changed by the Charlie Foundation. In the 1990s, she was a registered dietitian nutritionist at Children’s Hospital in Milwaukee. The hospital phones rang off the hook after Abrahams appeared on national news shows and produced a fictional movie starring Meryl Streep, First Do No Harm, that mirrored Charlie’s success on the ketogenic diet. Parents in Milwaukee wanted their children to try the diet, so a neurologist there asked Zupec-Kania to help start a ketogenic-diet clinic.

In doing her research, Zupec-Kania discovered old hospital records that showed that Children’s Hospital had offered the diet for children in the 1920s and ’30s. She later met a Milwaukee woman in her 60s who had spent her childhood Saturdays at the hospital, fasting and having her vital signs taken.

“She just wanted me to know that the diet had worked for her,” Zupec-Kania recalls. “She was seizure free and had lived a full, healthy life.”

Since becoming one of the world’s foremost experts on the diet, the dietitian has trained staff at 180 medical centers, including the UW’s, and has worked for the Charlie Foundation since 2006, developing materials and recipes.

She also consults with patients, under the supervision of doctors, who use the diet as part of their treatment for a variety of maladies from diabetes to severe migraines. One of her early patients tried it to quell seizures from an inoperable brain tumor. To the surprise of everyone, the diet slowed the tumor’s growth, and he lived a year longer than doctors had predicted.

Since then, Zupec-Kania has worked with many other cancer patients. The National Institutes of Health is running a clinical trial of the diet for glioblastoma multiforme, the most aggressive form of brain cancer. Other trials are looking at conditions such as autism, brain injury, and diabetes. Neurological intensive-care units at Madison’s American Family Children’s Hospital and elsewhere use the ketogenic diet to quell seizures in patients who are in status epilepticus, a dangerous condition of continual epileptic seizures.

Zupec-Kania’s latest work focuses on children with Prader-Willi syndrome, a genetic disorder that drives obsessive eating and dangerous obesity. She found that the low-carbohydrate diet improved children’s behavior by stemming their appetite and curbing food-seeking behaviors.

The Banff presenters also included physician Elizabeth Felton MS’02, PhD’07, MD’09, the driving force behind the UW’s epilepsy cooking class. Felton is a neurologist trained in dietary therapies at Johns Hopkins University, which kept the diet alive after it fell out of favor. The UW, which already had a diet clinic for children, recruited Felton to help create one for adults whose epilepsy is not well controlled by drugs. It’s the first clinic of its type in the state and one of just eight nationally for adults.

The adult diet is slightly less strict than the one Charlie Abrahams was on in the 1990s. Researchers have found that adults can tolerate up to 20 grams of carbohydrates a day without triggering seizures. (The diet is similar to the initial phase of the popular Atkins Diet.) Felton says that in patients whose epilepsy is not controlled by drugs, the diet brings about a 50 percent reduction in seizures for roughly half of patients.

“Typically we try medication first, but I wouldn’t say no if a patient really wanted to try the diet first,” she says. On the upside, her patients report feeling mentally sharper, and they often lose weight and exhibit improvements in blood pressure and diabetes. The trouble is sticking to a diet so different from the mainstream.

To cut carbs, the diet relies on nut flours such as almond and coconut, sugar substitutes, and lots of fats, including avocados and heavy whipping cream. But traditional recipes that rely on flour, sugar, and corn starch need tinkering to make them low carb.

“Cooking classes help take the mystery and stress out of starting the diet,” Abrahams says. “Compliance (with the diet) has to be 100 percent. You can’t take a meal off or a day off, or you could trigger a seizure.”

One of the patient chefs at the holiday keto cooking class in Madison learned that the hard way. Madison pediatrician Kristin Seaborg ’97, MD’01 was diagnosed with epilepsy as a teen, and like many with the condition, she found that drugs did not fully control her seizures. Her memoir, The Sacred Disease: My Life with Epilepsy, details her life as a physician and patient.

She started the diet at the beginning of 2016, after one last fling with holiday sweets. Like many, she found it easy to lose weight and found that the diet cut her seizures in half from two a month to one. But she missed carbohydrates so much that she had repeated dreams about chasing a giant piece of bread across a grassy field. After six months of dutiful adherence, she decided to cheat and have a single piece of cheesecake.

“The next day, I had multiple seizures and recurrent auras throughout the day,” she recalls. “I thought: ‘Darn it, this is working.’ ”

While she still misses carbohydrates, Seaborg says her biggest problem staying on the diet is lack of time. She and her husband have three busy school-aged children and a packed schedule of sports and other activities.

“It’s hard as a mom to cook for your family and then have to cook a separate menu for yourself,” she says. “I found myself cooking all day Sunday for them and then eating a whole bunch of peanut butter and cheese for my own meals.”

Seaborg says the holiday cooking class gave her inspiration to stay on the diet.

“That cooking class was really empowering,” she says. “I left there feeling pretty positive about it.”

Felton notes that fasting to stop seizures is mentioned in the Bible (Matthew 17: 14–21) and in the writings of Hippocrates, the ancient Greek believed to be the source of the saying, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.” Two millennia later, Hippocrates’s wisdom has become reality, in the form of green bean casserole topped with crunchy pork rinds and bacon, and a dollop of high-fat pumpkin cheesecake mousse for dessert.

Susan Lampert Smith ’82 is a media strategist for UW Hospital and Clinics.

Published in the Fall 2017 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.