A New Era for College Sports

As rules change for paying student-athletes, UW–Madison charts a path for success.

On July 1, 2025, the world of college athletics changed forever.

A few weeks after final approval of the landmark House v. NCAA settlement, universities began sending revenue-sharing payments directly to student-athletes. The date marked the definitive end of a system of amateurism that ruled college sports for decades but crumbled under legislative and legal scrutiny in recent years.

“It’s a different game now,” says Nolan Winter x’27, a star forward on the men’s basketball team at UW–Madison, which is among the large majority of Division I schools that have opted in to the new structures of the settlement. “I think there are benefits and also downsides to it.”

The hope for all parties — schools and student-athletes alike — is that the House settlement will bring some stability back to college athletics. Chaos has largely reigned since 2021, when a series of policy changes permitted student-athletes to profit from use of their name, image, and likeness (NIL) and to transfer schools unlimited times without losing playing eligibility. Lack of clarity on NIL rules has given rise to questionable recruiting practices as programs search for a competitive edge.

“The past four years haven’t been viewed as sustainable,” says UW athletic director Chris McIntosh ’04, MS’19. “It’s been highly unstructured, very vague, ever evolving. Having said that, I am proud of the way that our organization and our people have navigated these times.”

The House settlement establishes a framework for how universities can compensate student-athletes for the financial value they bring to their programs. (The case is named for one of the plaintiffs, Grant House, a former Arizona State swimmer.) It also creates oversight mechanisms to ensure that third-party NIL deals are legitimate, market-based sponsorships, rather than disguised payments to secure recruiting commitments — an escalating practice in recent years.

There will, of course, be winners and losers within this new model. Fortunately, Badger athletics has developed a playbook for success over the past four years: staying true to core values while embracing the change.

House Rules

This summer, Camp Randall opened its gates to concertgoers for the first time since 1997, with shows by Coldplay and Morgan Wallen. It’s part of the athletic department’s exploration of new revenue streams as it settles into the post-House era. Fans may have noticed other efforts of late, including Culver’s logos on the Kohl Center court and expanded alcohol sales in the Camp Randall concourse.

“We’ve operated in a way that’s been fiscally responsible, anticipating this change for years now,” McIntosh says. “It’s put us in a position in which we can and will contribute up to the limits of revenue sharing defined by House.”

For the 2025–26 academic year, that means UW–Madison will allocate $20.5 million directly to student-athletes. That maximum annual figure is expected to rise throughout the 10-year term of the House settlement, which caps the compensation pool at 22 percent of the average annual revenue that major Division I schools earn from broadcast rights, ticket sales, sponsorships, and other sources. The payments are on top of traditional scholarships and benefits, as well as third-party NIL deals. It’s up to the discretion of schools to decide how the compensation pool is distributed.

House v. NCAA Settlement, at a Glance

Revenue sharing: In the 2025–26 academic year, each school can pay its student-athletes from a compensation pool of up to $20.5 million. That cap represents 22 percent of the average annual revenue of major Division I athletic programs. Over the next 10 years, while the 22 percent formula remains, the compensation pool will grow as annual revenues increase. If 2035–36 revenue compares to today’s like a basketball next to a golf ball, then the funds for athletes will increase proportionally.

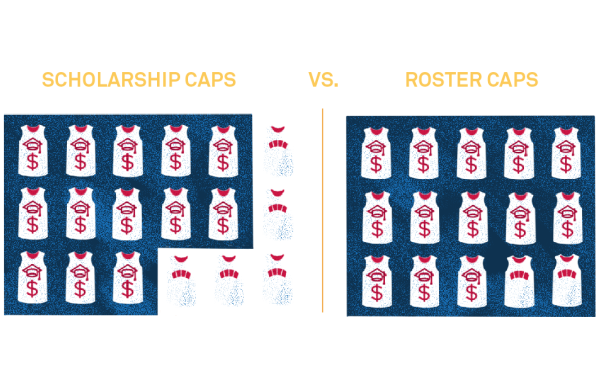

Roster limits: Replacing scholarship caps, each sport will now have a maximum roster size (e.g., 105 for football, 18 for volleyball, 15 for basketball). Teams can still roster non-scholarship walk-ons, but there could be less room for them.

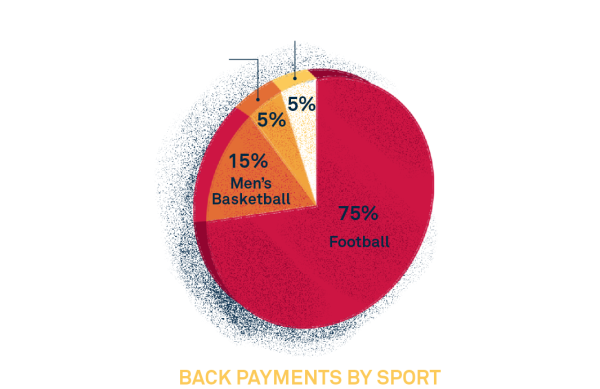

Back payments: The NCAA and its power conferences, including the Big Ten, will pay some $2.8 billion to student-athletes who did not have the ability to profit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) since 2016.

As part of House — a class action case that consolidated three federal antitrust lawsuits by former college athletes — the NCAA and its power conferences also agreed to pay some $2.8 billion in back damages to players who did not have the ability to profit from NIL since 2016. The negotiated formula earmarks roughly 75 percent for football players, 15 percent for men’s basketball, 5 percent for women’s basketball, and 5 percent for all others. The payouts (on hold as of July because of a legal appeal over the formula) will come from the NCAA, though partly by reducing its future revenue distributions to conferences and schools.

College Sports Commission: Largely replacing NCAA enforcement, the new entity and its chief operating officer will act more efficiently in sanctioning rule violations.

NIL contract review: Managed by the accounting firm Deloitte, the NIL Go clearinghouse will review all student-athlete name, image, and likeness deals over $600 to ensure they are for legitimate business purposes and true market value.

At the UW, the football and men’s basketball programs accounted for 75.3 and 13.6 percent of team-specific revenue, respectively, in 2024. Though several more sports generate revenue, those two are the only programs to run a profit and fund others.

Another structural change from the House settlement relates to roster management. The NCAA used to cap the number of scholarships schools could offer in each sport but did not limit roster sizes, creating lots of space for walk-ons. The settlement reverses the approach, removing the cap on scholarships but restricting the size of rosters. For instance, the new roster limit in football is 105 players, down from the 125 that the UW traditionally carried. The Badgers can now offer all 105 players scholarships, up from the prior cap of 85, though McIntosh notes that the walk-on tradition will remain at the UW.

In what was the final sticking point of the House settlement, any current student-athletes who might have been cut due to the new rule can stay on the team without counting toward the roster limit until their eligibility runs out.

As part of the grand compromise, while student-athletes can now receive direct revenue sharing, a new governing body will attempt to rein in some of the excesses of the early NIL era.

A Long Time Coming

After her freshman season in 2023, UW women’s basketball point guard Ronnie Porter x’26 opened up her Instagram direct messages to find a $25,000 NIL offer from Degree.

She thought it was spam. Eventually, she realized the deodorant brand was quite serious in recruiting her to its Degree Walk-On program, where she joined four other Division I athletes as brand ambassadors with a national platform. She used it to share her journey of overcoming adversity as an undersized, underestimated walk-on.

“I didn’t come from a lot,” Porter says, “so I’m able to use what I get from NIL to do what I wasn’t able to do growing up and also provide for my family. And that means everything.”

Porter, now a senior, has developed into a mainstay in the UW’s starting lineup and leveraged her success into other NIL arrangements. One of them is with Madison-based Exact Sciences. The health diagnostics company has developed an NIL program with an annual cohort of student-athletes. The deal includes social media sponsorships, community appearances, and tailored career coaching. UW volleyball player MJ Hammill ’24 even landed a job at the company after completing the program.

You’ve likely come across other NIL work. Pepsi and Mountain Dew splashed Johnny Davis x’24 and Braelon Allen x’25 on billboards. American Family Insurance and volleyball star Devyn Robinson ’24, MS’25 developed a social media campaign to celebrate her newfound voice as a role model. Rowing sisters Gracie ’25 and Libby Walker x’27, whose grandfather is a farmer and former UW rower, secured a sponsorship with the Dairy Farmers of Wisconsin.

“Those are the types of opportunities, where there’s value to all parties involved, that were a long time coming,” McIntosh says.

The UW was quick to get into the game. UW athletics established an NIL department in 2022, adding several dedicated staff positions that help student-athletes navigate the new world of opportunity. It provides educational programming around brand marketing and financial literacy, and manages a marketplace in which UW players can field sponsorship deals. Student-athletes also have access to UW Law School’s Law & Entrepreneurship Clinic for no-cost NIL contract review and legal assistance.

In a model reflected across college athletics, the UW has been supported by an independent nonprofit called The Varsity Collective. The group turns donations and business partnerships into the bulk of third-party NIL deals presented to UW student-athletes.

“Without them, I can’t imagine where we would be today,” McIntosh says. “They have stepped up at a time in which we desperately needed help, given the change of pace.”

The Wild, Wild West

The chance to create true business opportunities, McIntosh notes, is “what NIL was intended to be philosophically and what I hope it will be in the future.”

But in reality, before House, the national recruiting landscape often devolved into pay-for-play in the name of NIL — that is, school-affiliated donor collectives offering financial packages to players for their expected contributions on the field, not for the market-based value and use of their name, image, and likeness. Some states even passed friendly legislation to give their home universities expanded leeway over NIL deals and protection from sanctions.

The NCAA first enacted an NIL rule change in July 2021 after several states passed laws on the matter and the Supreme Court signaled a broad skepticism of the amateurism model in an antitrust case called NCAA v. Alston. Fearing more legal battles, the NCAA put few constraints on NIL. Primarily, it prohibited a school or its employees from directly paying a student-athlete.

The lack of NIL regulation, combined with unlimited transfers and the weak enforcement of existing recruiting rules, led to the wild, wild west. In addition to traditional recruiting, there’s been a scramble to retain current players and entice transfers — with NIL as an expanding part of the pitch. In a high-profile example from this past spring, a Tennessee quarterback skipped practice while seeking to renegotiate his NIL contract before entering the transfer portal and leaving for UCLA. (In June, the UW and Varsity Collective filed a lawsuit against the University of Miami for allegedly interfering with a football player who had signed NIL agreements with them.)

A key area of the House settlement aims to restore order to the college sports landscape and NIL in particular. A new entity called the College Sports Commission is taking over most enforcement efforts from the NCAA, which has long been derided for its inefficiency and inconsistency with rule violations around recruiting and impermissible contact. It will have wide latitude in assessing infractions and resolving appeals through arbitration.

The College Sports Commission will oversee other systems put in place by House, including the NIL Go clearinghouse. Managed by the accounting firm Deloitte, the clearinghouse will review all third-party NIL deals over $600 to ensure legitimate business purpose and realistic compensation using a market-value algorithm.

These reforms, McIntosh believes, will ultimately benefit the UW.

“Market-based NIL remains a huge opportunity for our student-athletes, and I think that’s an area in which Wisconsin can thrive,” McIntosh says. “We have an incredibly high level of engagement with sponsored partners and businesses, not just in the Madison market, but across the state and beyond.”

Core Values

Not all universities are as well positioned to succeed in the post-House era, either financially or competitively.

The Ivy League conference and a smattering of other schools opted out of the House agreement and revenue sharing altogether. The move preserves their existing financial model but leaves them without a major recruiting tool. Other universities have already cut smaller programs such as tennis, swimming, and track and field for fear of House’s financial fallout, a conversation that McIntosh insists is a nonstarter at the UW.

“Our priority is to preserve 23 sport programs at Wisconsin,” he says. “Broad-based opportunity is one of our core values.”

Badger fans have experienced the joys that come with a deep varsity sport lineup, even in these years of upheaval. Women’s hockey won the 2025 national title in an overtime thriller. Men’s cross country has won seven consecutive conference championships. Volleyball continues to sell out the Field House.

Last year, UW men’s basketball served as a notable case study for how to build a competitive team in an evolving landscape while sticking to your principles.

After the 2023–24 season, the Badgers lost a pair of key starters to lucrative opportunities in the transfer portal: point guard Chucky Hepburn x’26 left for Louisville, while leading scorer AJ Storr x’26 landed at Kansas. Many observers expected a down year.

In this era, some coaches would have searched the portal for splashy replacements to quiet the headlines. But not Greg Gard. He believed in developing his remaining roster and complementing it with players who would fit in well.

“Our strategy begins with retention and building around the student-athletes we’ve recruited since high school,” he says. “In addition, we’ve tried to be very smart about who we add as transfers to fill out our roster. Adding players who will fit in culturally, academically, and socially is just as important as how they’ll fit from a basketball standpoint.”

Enter John Tonje MS’25, a senior guard coming off an injury-ravaged season at Missouri where he averaged just 2.6 points per game. The unheralded transfer transformed into a superstar on the Badgers, scoring 19.6 points per game, earning All-American honors, and emerging as an NBA draft pick.

“The culture and foundation around him here at Wisconsin gave John an on-ramp to having immediate success,” Gard says. “He came in wanting to earn everything that was given to him.”

Gard’s belief in his roster and Tonje’s ever-steady presence proved contagious. Seniors Kamari McGee ’25 and Carter Gilmore ’25, underdogs who stuck with the program for years despite scant playing time, emerged as solid contributors. Nolan Winter and John Blackwell x’27 took big leaps in their sophomore seasons. Returning starters Steven Crowl ’24, MSx’26 and Max Klesmit ’25 rounded out a squad that, against the odds, improved its record to 27–10 and earned a top-three seed to March Madness. And by season’s end, ESPN rated Tonje the best transfer in all of college basketball.

Then in May, eight players from that team earned their college degrees. Perhaps surprising for the times, the graduation rate for student-athletes at UW–Madison has risen to a record 94 percent.

“It’s my number one point of pride from this past season,” Gard says. “As much as we talk about other things, graduating is still the end goal. In the recruiting process, academic success is nonnegotiable.”

The State of Play

In March, McIntosh traveled to Washington, DC, to testify in front of the U.S. House of Representatives subcommittee on antitrust.

“There is no doubt that college athletics is at an inflection point where the decisions made over the next couple of years will define the landscape for the foreseeable future,” he told the members.

The hope for all parties is that the House settlement will bring some stability back to college athletics.

For as many questions as the House settlement answers, it leaves the door open to even more. Antitrust lawsuits against the NCAA continue, including cases that aim to classify student-athletes as full employees and target rules such as the four-year eligibility limit. Uncertainty swirls around the intersections of House and Title IX, the federal law that ensures equal opportunity for men and women in college sports.

McIntosh believes stabilizing college athletics will require national legislation to preempt a patchwork of state laws, confirm the classification of student-athletes as nonemployees, and provide limited antitrust protections. (At press time, there was movement on a presidential executive order and congressional legislation around such issues.)

“We need safe harbor so that we can create common sense rules that are necessary to operate sport,” he says. Or as he told the subcommittee: “I don’t think we want 13-year college athletes.”

For the UW’s athletic director, preserving meaningful opportunities for future generations of student-athletes is deeply personal.

“My experience as a student-athlete transformed my life,” says McIntosh, who starred on Badger football’s offensive line in the late ’90s. “While so much has changed since then, the core of what this opportunity can do for a young person hasn’t changed at all — the ability to leave here with a degree from the University of Wisconsin, compete under the mentorship of world-class coaches and leaders, and grow socially.

“That’s the experience I want for all our student-athletes in each of their sports. What’s changed is how we deliver it.”