Art for All

What makes a good public painting or sculpture? Here are UW–Madison’s most successful works in plain sight.

The virtue of public art on a college campus is that students can interact with it however they wish. There’s no pressure or judgment, whether they contemplate the artworks to divine their meaning or routinely overlook them in the mad dash to class. Either way, the installations promise to be there the next day, a backdrop of the campus experience.

When I was a journalism student at UW–Madison, I can’t say I ever looked at Vilas Hall’s Freedom of Communication for more than a few seconds. But I do know that the building’s exterior would have felt naked without it. And now when I return a decade older (and wiser), I appreciate the mosaic’s artistry and message.

Fortunately, public art is patient.

Wisconsin ranks 49th among states in public funding for the arts. It spends 18 cents per capita, compared to Minnesota’s leading $9.62, according to the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. A major setback was the 2011 repeal of the state’s Percent for Art Program, which for three decades had funded artworks for new or renovated public buildings, including those at the UW.

But the university remains a sanctuary for public art, providing joy to passersby. Its collection grows every year and enlivens nearly every block of campus. Here’s a look at the UW’s most significant pieces and what makes them shine.

A Silent Teacher of Patriotism

Days after the firing on Fort Sumter in 1861, Wisconsin governor Alexander Randall ordered the state fairgrounds in Madison to be converted into a training site for Civil War soldiers. Carpenters turned cattle sheds into cozy barracks, and over the next four years, Camp Randall welcomed three-quarters of the 90,000 Wisconsin troops who served the Union. When they left for the front lines, they marched through the same Dayton Street entrance where the monumental Camp Randall Memorial Arch now stands.

The state dedicated the arch in June 1912 in front of hundreds of Civil War veterans. “This arch symbolizes the triumph of right over wrong, of freedom over oppression, the triumph of liberty-loving and freedom-enjoying citizens over those who enslave,” Col. Duncan McGregor said during an address. He added that the granite monument “fulfills all the demands of taste, solidity, and durability.” But not everyone agreed on that point.

In 1911, the state legislature had appropriated funds for the arch on the historic grounds owned by the UW. After a commission hired the Woodbury Granite Company of Vermont for the design and construction, the Wisconsin State Journal published a series of scathing editorials and critiques from national artists. The newspaper called the proposed design “inartistic,” “inappropriate,” and “a laughingstock.” Architect John Russell Pope wrote, “I do not remember of ever seeing anything anywhere that has less either sculptural or architectural qualities than this thing.”

In the face of public pressure, the commission announced that it would redesign the arch and work with architect Lew Porter, who was already supervising the construction of the state capitol. It’s not clear how much of the design was altered, as the final product closely resembled the earliest published plans of a roughly 30-foot-high monument.

Perched atop the monument is Old Abe, the bald eagle that served as mascot for the Eighth Wisconsin Infantry. Two statues, representing a young soldier and an old veteran, flank the arch. Interior plaques commemorate the regiments that trained there. And nearby, a marker for the Lincoln Heritage Trail honors the Union’s commander in chief. The marker ties the arch to another iconic work of the era: Adolph Weinman’s bronze Abraham Lincoln atop Bascom Hill.

The Camp Randall Memorial Arch symbolizes the triumph of right over wrong, of freedom over oppression.

Today, the Camp Randall arch is widely cherished as both a historical symbol and a striking entrance to the stadium grounds. As a Civil War veteran who praised the monument wrote to his fellow soldiers: “Long may it stand, a silent teacher of patriotism.”

The Greatest Lumberjack

When the Memorial Union opened in 1928, its rustic Paul Bunyan Room on the first floor transported visitors to the logging bunkhouses of northern Wisconsin. Flagstone flooring, hewn oak furniture, and warm lighting imitated the quarters where workers passed time by telling tall tales of the greatest lumberjack of them all. And it’s in this room that a young UW artist brought the lore to life with the world’s first Paul Bunyan murals.

In James Watrous’s Paul Bunyan Murals, Babe the blue ox grows so fast that he busts out of his barn. Althea Dotzour

As part of the New Deal in 1933, the federal government established the Public Works of Art Project to employ artists and beautify buildings with American imagery. James Watrous ’31, MS’33, PhD’39, then a graduate student and later an art professor, earned a $25 weekly wage to fill the Paul Bunyan Room’s walls.

“It seemed a bountiful wage to a young, unemployed artist,” he later wrote.

Although funding dried up six months later, Watrous vowed to finish the 11 panels and two maps on his own dime. Each piece took considerable time to complete because of his finicky medium: tempera, an ancient paint mixture of powdered pigment, water, and egg yolk. The bygone technique gives the Paul Bunyan Murals a bright, distinctive luster, with blues and reds boldly emerging from earth-tone scenery. Watrous finished the set in 1936.

The whimsical drawings cover a range of Bunyan legends: his dayslong fight with the big Swede Hels Helsen, which carved the Black Hills; his blue ox, Babe, who grew so fast that he busted out of a new barn every night; his blacksmith, Big Ole, who sank a foot deep in solid rock when he held the ox’s iron shoes.

If you examine the murals closely, you can spot one with a slightly different styling and sheen. That panel tells the story of chief cook Sourdough Sam, whose “griddle was so big that his flunkies greased it with bacon slabs strapped to their feet.” Watrous re-created it in 1993; the original, which drew from folklore, depicted the workers in a racially insensitive way.

That same year, UW students formed the Multicultural Mural Committee at the Wisconsin Union. Their effort led to Chicano artist Leo Tanguma’s The Nourishment of Our Human Dignity and The Inheritance of Struggle in 1996. Neighboring the Paul Bunyan Room, those murals show representation in art at its best.

Watrous died in 1999, but his presence on campus still looms large. Shocked upon learning in 1939 that the UW was storing artworks in Bascom Hall’s basement, he tirelessly campaigned for a campus art museum to preserve the university’s collections. When the Elvehjem Art Center opened in 1970, Watrous was widely recognized as the driving force.

An Unspoken Bond

Outside the north end of UW–Madison’s Elvehjem Building sits Mother and Child. Stoic, protective mother stares into the distance; innocent, carefree child folds his arms into her chest, their two figures becoming one. Anyone can relate to their unspoken bond and unconditional love.

The life-size work is one of six authorized bronze casts made from William Zorach’s Spanish marble sculpture. The original Mother and Child won a show prize from the Chicago Art Institute in 1931 and found a permanent home at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The UW acquired its Mother and Child in 1977 as an anniversary gift from the Class of 1927 to the fledgling Elvehjem Art Center (now the Chazen Museum of Art). The sculpture, originally installed by the south entrance on University Avenue, was envisioned as the first of several to surround the building. While such an ambitious sculpture garden never came to be, Mother and Child now anchors a courtyard of its own. The quiet, contemplative setting suits a work that Zorach described as his “finest piece of sculpture.”

He wrote: “There is nothing more emotionally significant than the relationship between mother and child. … Life exists through them and could not exist without them.”

Creative Problem-Solving

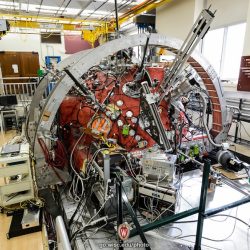

In 1994, UW–Madison transformed an unsightly parking lot in front of Engineering Hall into something of an actual park with green space and tree-lined walking paths. The centerpiece of this reimagined Engineering Mall is a 4,500-pound, 18-foot-tall stainless steel fountain that tends to overshadow it all — by design. Meet the mighty Máquina.

Spanish for “machine” and alternatively called the Descendant’s Fountain, Máquina marries art and engineering. Saint Louis–based sculptor and UW alumnus William Conrad Severson ’47 — who donated the piece in memory of his father, Edwin 1921 — wanted it to represent “engineering tools and the engineer’s role in creative problem-solving.”

The fountain’s pair of half-disk pieces appear suspended in air, perpetually on the verge of interlocking. Their C-like shape resembles precision measuring tools. For years, Máquina’s internal jets produced steady streams of water that traveled down the sculpture and along a channel to a reflecting pool on the opposite end of the mall. The fountain was connected to computers that could synchronize the mall’s lights, speakers, water patterns, directional stream, and compressed air functions. The fountain’s winter mode produced hanging icicles; in warmer months, “Westminster Chimes” and UW school songs rang out as jet streams pulsated to the melody.

The College of Engineering and Dean John Bollinger ’57, PhD’61 long championed Máquina as a hands-on laboratory for students. As late as 2009, student groups met in an underground control room to maintain it and design new features. These included motion-sensor columns that could manipulate water patterns with a wave of the hand; an internet livestream that allowed viewers to remotely control the fountain; and a touch screen in the Engineering Hall lobby with similar functions.

But the water stopped flowing over the last decade. With outdated technology and patchwork programming, simply running the fountain became a challenge of its own. The control room no longer meets modern safety regulations, and the water pipes and pump system likely need to be replaced. The college has instead turned its attention to a new engineering building, for which it secured funding this year.

Máquina may have met its functional demise. But as an art piece, it still fulfills the original vision that Severson outlined three decades ago: to be “a provocative image that is imprinted upon the mind and experience.”

Overwhelmed with Light and Color

Legendary glass sculptor Dale Chihuly MS’67 has often credited water as a source of his creativity, with a custom plastic clipboard and wax pencil next to his shower as proof. While studying at the nation’s first studio glass program at the UW in the mid-1960s, he chose to live in a small cabin on the shores of Lake Mendota.

“I remember the sparkle of the lake,” Chihuly said in 1997, the same year he was commissioned for an art installation at the new Kohl Center on campus.

That lake view inspired The Mendota Wall, all 1,284 blown-glass pieces. Their radiant greens, blues, reds, and yellows reflect the colors of sunlight hitting the water. The 140-foot wall installation — Chihuly’s largest at the time — greets visitors as it spans the Kohl Center’s curving main concourse. More than 100 spotlights, each carefully positioned, brilliantly illuminate the glass.

Chihuly’s art installation at the Kohl Center is “a wall of effervescence.” Althea Dotzour

The blown-glass pieces of the 140- foot Mendota Wall reflect the colors of sunlight hitting the water. Jeff Miller

Althea Dotzour

“I want people to be overwhelmed with light and color in some way that they’ve never experienced,” the Seattle-based artist has famously said. And by that measure, The Mendota Wall delivers.

If you try, you can identify around 50 clusters of glass in varying shapes and sizes. But as with counting waves, the number turns arbitrary. Scattered, onion-like bulbs sprout coils and tendrils that intersect and curl over each other. Chihuly considered the installation part of his series of “anemone walls,” and indeed, the tentacle glass forms look like they could have come from the bottom of the sea.

The blown-glass pieces of the 140-foot Mendota Wall reflect the colors of sunlight hitting the water.

The state paid $144,000 for The Mendota Wall. Chihuly’s proposal read simply: “A wall of light. A wall of effervescence. A wall of color.” By the time it was done, Chihuly estimated that the piece was worth close to $1 million. He considered the balance a gift to the university “that was seminal in my career.”

Harvey Littleton, the late UW art professor and the pioneer of studio glass, applauded his former student’s “riot of color” in The Mendota Wall.

“It brings joy to the building,” he said.

The Holy Trinity of Nature

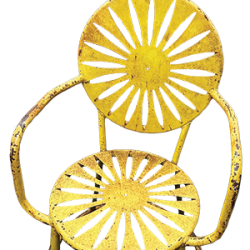

UW–Madison’s Botany Garden on University Avenue boasts more than 500 species of plants from around the world. But one flower stands far above them all: a saucer magnolia, carved in limestone as part of the three-piece Essence sculpture that dots the garden’s winding paths.

The Flower joins the The Seed and The Fruit in honoring fundamental stages of the plant life cycle. Susan A. Falkman’s works were commissioned in 2004 during an expansion that doubled the Botany Garden’s footprint.

Precise detailing and intricate textures unite the limestone pieces, but each can stand on its own. The Seed captures the intimacy of a plant emerging from the earth and into the light as a chrysalis wrapped by tender leaves. The Flower, placed near the garden’s magnolia family, lives up to the natural beauty of full bloom through its delicate rendering. And The Fruit, sited by the Newton Apple Tree, provides a playful note with its half-eaten state and exposed core. A lone seed dangles from the apple’s core, leaving us with the promise of new life.

The Seed captures the intimacy of a plant emerging from the earth and into the light as a chrysalis wrapped by tender leaves.

The Fruit provides a playful note with its half-eaten state and exposed core. Ingrid Jordon-Thaden (3)

Falkman, a Wisconsin-based sculptor who refined her craft in Greece and Italy, wanted the work to stay true to “the essence of a botanic garden — the holy trinity of nature,” she says. But for the close observer, she left other secrets to discover. The apple’s uneaten back side, for example, takes the shape of a female torso. From a certain angle, The Seed looks like a caped monk figure on the move.

Still, Falkman’s chief interest is the purity of the magnolia blossom.

“The streaming of life’s energy,” she says. “I love carving that.”

The Threshold to the Rest of Your Life

As you enter Nancy Nicholas Hall, home of UW–Madison’s School of Human Ecology, Threshold greets you across the main foyer. The giant mosaic proves the ultimate statement piece, spanning 20 feet across the wall and sparkling with vivid color.

Appropriately, Threshold commands the connection point between the old building and the large new addition, which opened in 2012. But Chicago-based artist Lynn Basa drew inspiration from what lies behind the mosaic’s wall: Observatory Hill. A series of spherical onyx orbs — originally aglow with LED backlighting — invite observers into a new dimension.

“If you looked all the way through the hill that it’s against, you’d see the lake on the other side,” Basa says. “The idea of the glowing onyx was students being able to see into their future through these tunnels or openings.”

Human ecology explores the interplay between people and their environments, so Basa also played with motion, flow, and connectedness. Threshold features dramatic changes in scale: the massive onyx orbs; the medium-sized, bean-shaped slabs of brown marble; and the tiny pieces of Byzantine glass, smalti, and ceramic tiles. Strings of tesserae drift from one end to the other, linking all parts to the whole. Dominant greens are joined by mesmerizing blues, browns, and gold. A sprinkling of reflective tiles project an even broader range of color.

The backlighting has since burned out, but the mosaic still glows under skylights and stands as a remarkable technical feat. “You don’t see any other mosaics where people use all those materials,” Basa says of the painstaking process, “and now I understand why.”

The title Threshold represents more than just the piece’s physical location. It also speaks to the students who pass by it every day.

“College is one of the most significant, formative times in any person’s life,” Basa says. “You’re not the same person coming out as you were going in. You’re on the threshold to the rest of your life.”

“We Will Survive”

In September 2023, Effigy: Bird Form found its way home. The Truman Lowe MFA’73 sculpture, first displayed at the White House a quarter century prior, secured a rightful resting spot on UW–Madison’s Observatory Hill near the Native burial mounds that inspired it.

Lowe, the prominent Ho-Chunk artist and longtime UW professor, was commissioned for the Honoring Native America exhibition that opened at the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden in 1997. It was the first collection of contemporary Native fine art to be shown at the White House, earning the praise of First Lady Hillary Clinton for “truly express[ing] our millennium themes: to honor the past and imagine the future.”

Before the UW acquired it, Effigy was on display for more than 20 years at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo.

The sculpture is made of dozens of two-inch aluminum rods, curved and welded together to form the skeleton of a bird. Its lattice outline gives “a sense of invisibility of the entire form,” Lowe said, to honor “those mounds that have disappeared.” The bird hovers just above the ground with wings fully spread, posing almost like a fighter jet. The horizontal design was intentional: Lowe wanted Effigy to be visible from the presidential helicopter at the White House.

Lowe, who died in 2019, was particularly inspired by a bird mound on Observatory Hill with a wingspan of 50 feet. Effigy now keeps watch over the mound and its neighboring two-tailed water spirit. Dozens of other mounds are extant on campus, which occupies the ancestral land of the Ho-Chunk.

Tragically, many mounds in the area have been destroyed by agricultural and urban development over the last two centuries. And so Effigy’s permanence may be its most powerful message.

“This is my attempt to pay my respects, to celebrate the longevity of our history and our traditions,” Lowe said of the sculpture. “We have endured, and I know we will survive.” •

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a senior staff writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Summer 2024 issue

Comments

Tom Zinnen May 30, 2024

Amen. Public art helps us tie together connections across the human experience.

I enjoy showing visitors the John Steuart Curry murals in Biochemistry (which helped save the building from the wrecking ball ~14 years ago) and Curry’s “Freeing of the Slaves” in the Law Library (https://publicart.wisc.edu/john-steuart-curry-freeing-of-the-slaves/).

The latter pairs with Curry’s “Tragic Prelude” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tragic_Prelude) in the Kansas State House in Topeka.

More on the murals at PBS Wisconsin’s “University Place”:

https://pbswisconsin.org/watch/university-place/university-place-restoration-john-steuart-curry-murals-ep-695/

Meg Hamel June 4, 2024

The author mentions “Freedom of Communication,” the mosaic on the north face of Vilas Communications Hall. This work was also created by Prof. James Watrous, whose Paul Bunyan murals are described in the story.

Prof. Watrous also made mosaics for Ingraham Hall, Sewell Social Science Hall, and the Memorial Library, along with other works for UW–Madison.

His legacy as a much-loved teacher and champion of Wisconsin artists lives on in the James Watrous Gallery of the Wisconsin Academic of Science, Arts, and Letters, open to all under the glass dome in the Overture Center.