Into the Unknown

What’s the future of UW–Madison? We asked the experts to find out.

When LaVar Charleston MS’07, PhD’10 thinks about the present, his mind turns to his table.

“Sorry,” he says as I quickly pull my water bottle back and wait for a coaster. The office in Bascom Hall isn’t luxurious — like many spaces in the old, old building, it seems to have been assembled piecemeal: his office and an outer office subdivided from a larger room that had been meant for some other purpose.

“This table’s very fragile,” he continues. “If you put your glasses down too hard, it scratches. Had I known it was that dainty, I would not have gotten it.”

Had I known.

The words hang over this assignment. On Wisconsin magazine wants an article that gives a view of the future, and in particular, of UW–Madison’s future. But Had I known could be the three-word motto of the human race. We’re bad at anticipating the future.

When the architect William Tinsley designed Bascom Hall in 1857, the UW regents told him they wanted it to serve as the UW’s main building, and it should have rooms for recitation, lecture, library, laboratory, and an astronomical observatory. “In a word,” they said, using many more words, “it should be plain, substantial, comfortable, and exactly adapted to the purposes for which it is designed and no other.”

Had they known.

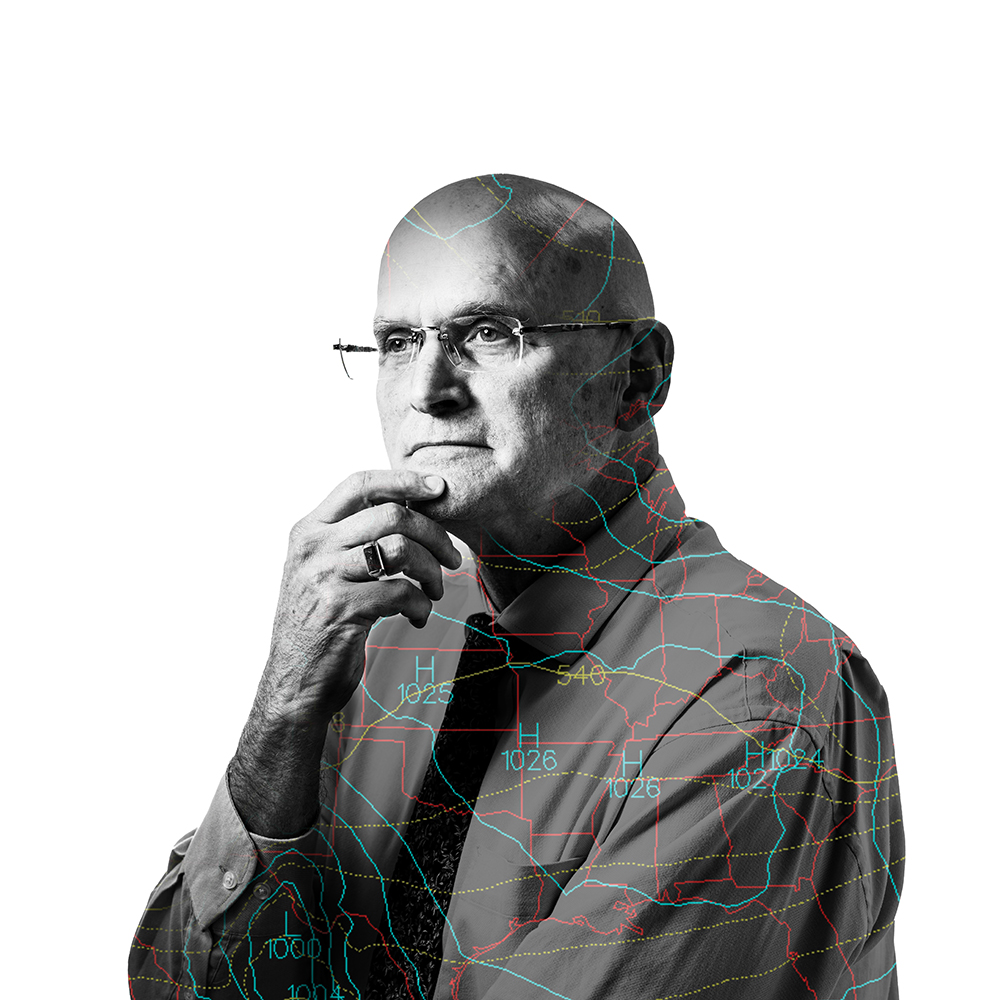

LaVar Charleston says the UW must prepare grads to live in a global society. Althea Dotzour; Bascom Hall by Bryce Richter

The regents had not imagined, in the middle of the 19th century, that the university would ever grow much larger than the 169 students it then hosted. They didn’t know that the astronomy equipment would leave for Washburn Observatory in 1878 and the labs for Science Hall in 1875. They didn’t guess that what would come to be called Bascom Hall would later host military instruction or a water tower. They couldn’t imagine the UW as the institution we see today, with 13 constituent schools and colleges, 49,886 students, and 24,232 faculty and staff, including a person who holds the 26-word title of deputy vice chancellor for diversity and inclusion, vice provost and chief diversity officer, and Elzie Higginbottom Director of the Division of Diversity, Equity & Educational Achievement. Bascom Hall, which is certainly substantial but neither plain nor comfortable, serves many purposes other than the ones it was designed for, which is why its ancient rooms have been carved up for offices with the addition of haphazard-seeming interior walls, frequently reconfigured electrical wiring, and the occasional delicate table.

When LaVar Charleston thinks about the future, he — well, we’ll get to that. Thinking about the future is easy. Knowing it is hard.

To find out what UW–Madison will be like in the future, I sought out experts in just about every aspect of university life and function. And I found people willing to admit that the future is unclear but who are doing their best to project from current trends.

“In order for students to be more successful, you have to have cultural intelligence skills.”

— LaVar Charleston

***

Had I known how difficult this assignment would be, I might have set that first paragraph somewhere else — not in Bascom Hall, but in Memorial Library. If a university is the sum of what it knows, then librarians are the people to talk to. It’s the librarian’s job, in the words of Lisa Carter, to acquire, preserve, steward, and distribute information — that is, to know stuff. And Carter should know what librarians do. She’s UW–Madison’s vice provost for libraries and university librarian.

Her office is in Memorial Library, which opened in 1953 with shelf space for 1.2 million volumes. As the university then owned about 600,000 books, it seemed well prepared for the future. But by 1960, it was already too small, and UW president E. B. Fred griped that operating a modern university with this cramped library was “like trying to run an 80-cow farm with a 20-stall barn.” Fred, evidently, was not given to high-tech analogies, even when pondering the future.

University librarian Lisa Carter sees the demand for digital materials rising, but the UW also continues to add printed books as fast as ever.

I went to Carter not simply because librarians know things, but also because libraries are under considerable pressure to change to keep up with technology. Over the last 20 years, the publishing world has increased the number of books and journals produced digitally, and rather than turning to subject experts, people often go to search engines. Who needs a library when Google can scan the entire internet and when books, journals, magazines, and newspapers from around the world are available to any laptop with access to Wi-Fi?

“That hard copy, the hard magazine, is going away,” says Steve Ackerman, UW–Madison’s vice chancellor for research and graduate education. “It’s been a long time since I got a [paper] journal — it’s all online now.”

If he only knew.

It’s true that the libraries have added a lot of digital material over the past few years, and that trend is likely to continue. But the libraries are also adding physical materials just as fast as ever.

“Humans are eternally ingenious and are continuously creating new ways of storing and sharing information,” says Carter. “It’s not a zero-sum game. Scholars’ demand for print has not been completely replaced by requests for electronic resources.”

While there’s a greater demand to have access to materials digitally, the libraries have to keep both print and digital materials. “People are still generating books. People are still generating print journals. People are still generating vinyl LPs. New artists are generating physical objects,” Carter says. “And it’s not always looking forward — people may want access to a book that was printed 500 years ago.”

Currently, the UW Libraries boast more than 7.3 million printed volumes and 6.2 million microforms — documents stored on microfilm or microfiche. The libraries have digitized more than a million pages of texts and images and receive 20,000 academic journals digitally.

The soaring demand for digital materials is forcing UW–Madison’s libraries to evolve their thinking. For one thing, Carter expects them to increase their connections with other university libraries, both within and outside Wisconsin, essentially giving future UW students access to a super-library. UW–Madison is involved with the HathiTrust, which aims to share digital materials from hundreds of research libraries around the world, including all 14 Big Ten schools. As of last fall, it had collected digital versions of 17.6 million volumes, making 6.1 billion pages available to the UW community.

“The trajectory toward interdependence between libraries and within libraries is going to get stronger,” says Carter. “We’re going to be even more interdependent upon one another. We are going to see creative uses of new technologies to solve some discovery problems.”

As digital demand increases, the libraries of the future will need to balance the ongoing need for physical browsing with the ever-increasing need for multifunctional, flexible spaces. The libraries are not only working to address multifaceted space challenges, but also securing preservation-quality space to ensure proper care for their aging physical materials. Recently, the libraries announced funding for a 38,000-square-foot expansion to their high-density Verona Shelving Facility. The space provides the ability to manage and care for fragile materials and frees up space on campus.

“Some part of Memorial Library is always going to have browsable sections,” says Carter. “But there’s a lot of space in this building that’s not used to its full advantage. And could we unlock some of that to be communal gathering space, spaces where faculty and students come together with librarians to work in groups and bounce ideas off one another?”

For librarians, Carter foresees a role that grows in complexity as they become greater research and teaching partners for faculty and students. “We have to be experts in the old way of doing things as well as emerging forms of knowledge exchange. Because no matter how much information is out there, there will always be things that you can’t find digitally.”

***

Had Steve Ackerman known that I’d use his line about digital journals to suggest libraries’ obsolescence, he might not have said it. As much as he believes in digital publishing, Ackerman is on the side of the librarians. He does not believe that they can simply be replaced with internet browsers.

“A librarian’s going to point you to the answer you need,” he says. “Google’s going to point you to the answer they want you to have, and that’s not how research should be done.”

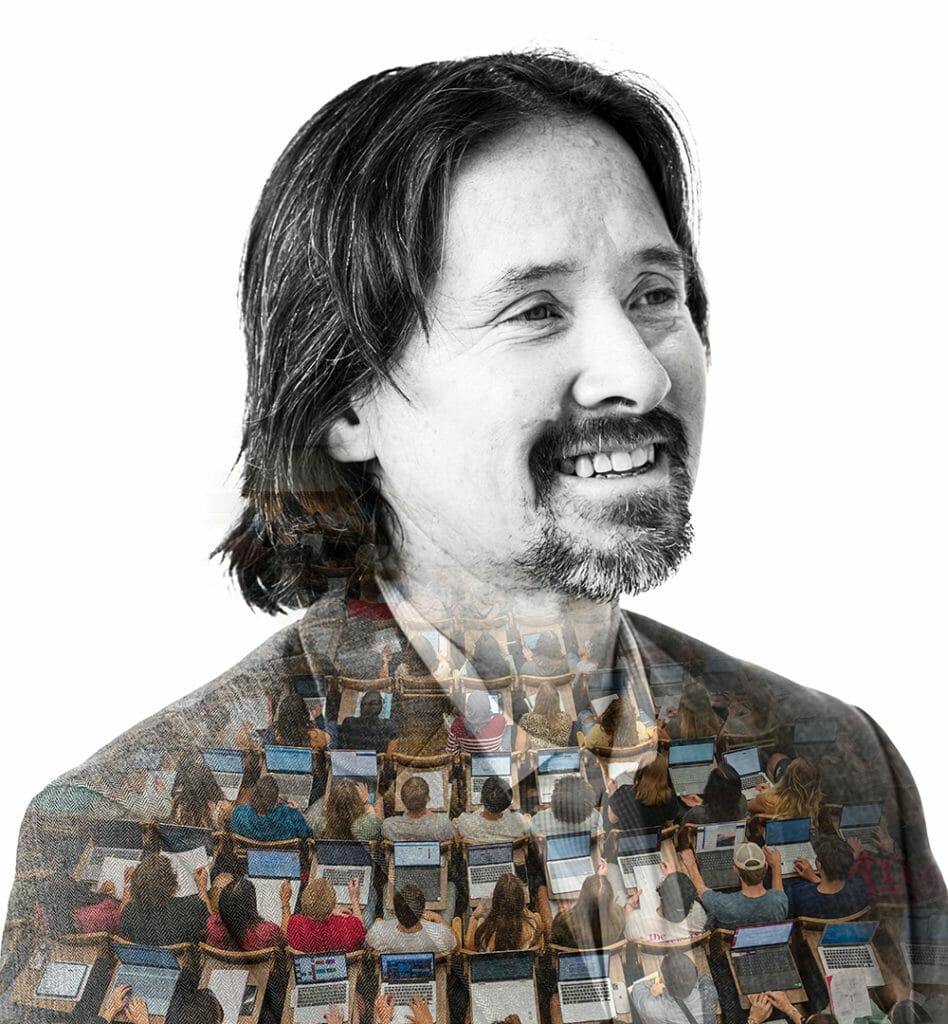

Steve Ackerman believes that artificial intelligence will change research by increasing our ability to collect and process data. Bryce Richter; satellite by lab of Steve Ackerman

This is why I went to talk to Ackerman. If a university is the sum of what it discovers, then Ackerman is the person to see. Plus, I wanted to find an accurate picture of the future, and he likes good information, not just popular information. Also, he’s a space scientist, which is kind of future-y — though Ackerman does not use spaceships to explore strange new worlds and seek out new life and new civilizations; rather, he uses them to understand our own.

“Wisconsin is the birthplace of weather satellites,” he says. “I like to get that message across.”

Ackerman came to the UW in 1987 to work at the Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies, or CIMSS. There, he started as a researcher, but after five years of just doing studies, he decided he wanted to teach, and so he joined the faculty in 1992. In 2014, he accepted the role of vice chancellor for research, though had he known what that meant, he might have had second thoughts.

“It’s not much teaching,” he says, “and that’s a disappointment.”

Ackerman oversees the UW’s present research enterprise, and he’s also responsible for planning how it will evolve to support the UW–Madison of the future.

“The interest among humankind is to ask questions and try to get answers to those questions,” he says. “We look at the world around us, and make observations, and then try to understand what those observations are coming from. That aspect won’t change.”

But research capabilities are growing, especially in terms of computer power — and in the ways that computers assist researchers to increase the amount of information they can comprehend. Like Carter, Ackerman sees a world in which there will be an overwhelming amount of data to consider — perhaps too much for the human mind to process on its own.

“One thing we’re seeing more and more of,” he says, “and I think that this is going to explode, is the application of artificial intelligence to apply to the data that we’ve collected.”

Thirty years ago, when Ackerman was a young scientist, he had a grant from NASA to improve the ability of satellites to detect clouds. But NASA put three conditions on his work: first, it had to produce a process that could analyze data in real time — there’s no advantage to predicting the weather after it happens; second, his process couldn’t generate more than four gigabytes of data a day, because that would overwhelm the available computers and make condition one impossible; and third, it could not rely on artificial intelligence, because NASA didn’t trust AI. Ackerman succeeded at the project, but the last two limitations would seem ridiculous today.

“Now I have a different project from NASA to look at cracks in the Arctic Sea ice, and we’re using AI all the time,” he says. “It’s so much better.”

The current project uses satellite images to see how ice near the North Pole breaks up, comparing new images to historic satellite photos to determine climate change’s effect on the oceans. “We’re trying to look at, over the historic record of the satellites, what’s changing about sea ice concentrations,” he says. “We’re using AI techniques to compare [large volumes of past data]. When you see [fractures] in the ice now, you think, ‘Okay, this is really different.’ ”

"The interest among humankind is to ask questions and try to get answers. ... That aspect won't change."

— Steve Ackerman

In the future, Ackerman believes, researchers will apply AI across a wide range of disciplines — the sciences, humanities, even the arts — to dramatically increase the amount of information they can study. The growth in ability to process data will then lead to a growing appetite to generate data, which will mean more physical infrastructure: wet labs for biological research, high-powered scientific instruments, and outdoor labs for environmental sciences. To support all this, the UW will need to generate and supply increasing amounts of energy.

“We need to upgrade our electrical power for sure,” he says. “If there’s a blip in the electrical power, then boom, boom, boom, a bunch of stuff shuts down. Some of it doesn’t come back up right away, and you damage tens of millions of dollars of instruments, and it takes decades to fix them.”

***

Energy is a leading concern for Cindy Torstveit ’91, the university’s associate vice chancellor for facilities planning and management (FP&M). If a university is a collection of buildings, grounds, and infrastructure, she’s the person who’s most responsible for UW–Madison’s future.

“Power delivery is changing a lot,” she says, “and we’re kind of watching that … looking at where we can become more efficient.”

Cindy Torstveit and the staff at facilities planning and management are trying to help the UW reduce its carbon footprint. Bryce Richter; solar panels by Jeff Miller

Just over a decade ago, the UW’s Charter Street Heating and Cooling Plant used 150,000 tons of coal a year. The university began phasing coal out in 2010 and recently has earned honors for its efforts to become more energy efficient.

“How can we reduce our carbon footprint, meet our sustainability goals — that’s really important,” says Torstveit. “But also, we have to provide reliability, redundancy, resiliency in our service.”

I went to Torstveit to find out what the physical campus of the future would look like, and she believes the UW will turn more to “power diversity,” generating energy from more renewable sources. A little over a year ago, FP&M’s Office of Sustainability worked with students to study using solar panels to power lights and displays at bus shelters, and the university formed a partnership with Alliant Energy to create a small-scale solar-power-generation facility.

Torstveit sees that kind of diversity — really, flexibility — as the hallmark of the future of campus. She looks at Bascom Hall, with its changing functions and subdivided offices, as one of the UW’s great success stories. Reuse and repurpose: those are the keys to survival. “Bascom has evolved over time,” she says. “It’s still there, and I don’t think it’s going to go anywhere.”

The near future is Torstveit’s focus, though with a hope that she’ll prepare the UW for a more remote future. She and her staff are preparing to start work on the next campus long-range plan, to be published in 2025. She intends the university’s new facilities to incorporate flexibility, to offset the difficulty of had we known.

“We don’t have a crystal ball, right?” she says. “We don’t know exactly what the future’s going to be, and we can’t predict it, but we are preparing for it.”

To make her point, she cites the pandemic. Until February 2020, the UW did not focus much on video conferencing or online learning. That changed suddenly and unexpectedly in March 2020.

“Now it’s very common for us to have video conferences,” she says, and as she and I are meeting on Zoom, I concede the point.

But that’s now, not the future. Torstveit doesn’t foresee UW–Madison becoming a fundamentally virtual university.

“So much about being at the University of Wisconsin is being on campus and that campus culture and how we learn together,” she says. “I can say for sure that we will always have a residential student population, because that’s who we are.”

***

Matthew Hora PhD’12 thinks that if people knew more about climate change, they would worry less about virtual learning.

“There’s definitely [new] technology, artificial intelligence, online learning — that’s all there,” he says. “It’s going to accelerate, and it’s going to change how the university functions and operates, especially within the teaching and learning space.”

But climate, he says, “is the big one. We need to be preparing our students across all the disciplines about how climate will be affecting their lives, but we’re not.”

Matthew Hora sees increasing pressure on universities to prove that education prepares students for the working world. Bryce Richter; classroom by Althea Dotzour

Hora is an associate professor in the Division of Continuing Studies, and he studies teaching and learning. If you think of a university as fundamentally a teaching institution, then people like Hora have the best view of the future. To be clear: he doesn’t see virtual learning as an inevitable future for UW–Madison, and he doesn’t necessarily think it’s a good thing. During the COVID pandemic, for instance, he studied the effect of virtual learning, especially for internships. “There was a question: does being present really matter?” he says. “It does.”

The real change that’s coming to teaching, both at the UW and at universities in general, is driven not by technology but by politics and economics: a rising demand that universities prepare students to enter the job market.

“That’s part of the critique,” Hora says, “that [universities are] not preparing students for the real world, the world of work. Community colleges are, and professional programs like nursing are. That rhetoric, those critiques, they’ve had a huge impact. Research on employability — how well is higher education preparing students to get a job? — that’s international, and it’s growing.”

But if parents and government leaders knew what the hiring market is really like, they might not be so keen on direct vocational training. Employers want to hire critical thinkers and problem solvers — the very traits that an interdisciplinary, liberal arts education provides.

“Despite all the rhetoric about skills-based hiring, about employers saying they’re not going to look at education credentials anymore, they still matter,” Hora says. “A four-year degree is the currency of the labor market. It matters, not just the presence of a four-year degree, but where you got it. Maybe employer behaviors will change, but I’m not seeing it.”

To better prepare students for the jobs of the future, universities will have to train them to be flexible: not to perform specific skills but rather to have the ability to understand and solve unforeseen problems.

“You’re most likely not going to stay in one job your whole life,” Hora says. “The world is going to be disruptive, like it has been for the last few years, and things are going to change in ways we don’t know. Look at the pandemic. Look at the climate. Things are going to happen, and you’re going to have to be ready for that.”

Hora knows about unpredictable career change: had he known where his path would take him, who knows what he might have studied as an undergrad? He earned a BA in English from the University of California–Santa Barbara and then became an organic farmer. He went to graduate school for anthropology and then came to UW–Madison for a doctorate in educational psychology. Good teaching, he argues, actively engages students so they are truly learning to think. And this is what UW–Madison is increasingly doing. Programs such as Delta, which trains graduate students and postdocs to be better teachers and mentors, show that the university is helping instructors learn the craft of teaching.

“I see great positive signs that these ideas are being taken seriously,” he says. “Somebody said that the pace of change in higher education is glacial, but I don’t see that. The change in the last 10 or 15 years has been remarkable.”

In the last 10 or 15 years, I point out, the change in glaciers has also been remarkable. He pauses. In the future, we will need new metaphors.

“Well,” he says, “when I look around here and think about the future, I see this area growing massively. We have water, and we have a temperate climate. The people who can’t live in Miami and Phoenix anymore — where are they going to go? Right here.”

"We don't know exactly what the future's going to be, and we can't predict it, but we are preparing for it."

— Cindy Torstveit

***

Which brings us back to LaVar Charleston in his subdivided office in Bascom Hall. If a university is the aggregate of its students, then Charleston is watching UW–Madison change. In the future, when those people come from Florida or Arizona or wherever, he wants to make sure that UW–Madison helps them — and their Wisconsin-born classmates — thrive in the working world they find afterward. The university, like the United States, is becoming more diverse.

“Increasingly, we have a more global society,” Charleston says. “In order for students to be more successful, you have to have cultural intelligence skills. You must be able to engage in diversity and difference to be effective.”

In the last 10 years, he notes, the share of UW–Madison’s faculty who are people of color has grown from 18 percent to 25. Among students, the share of people of color has grown from 14 percent to 20, and a fifth of all undergrads are now first-generation college students.

So what will the UW student body look like in the future? “My hope is that we are the destination of choice for students who have historically been marginalized: an ideal place to get a top-notch education and be prepared to be a leader in the world,” Charleston says. “I don’t think that’s impossible.”

In other words, if Charleston succeeds, the UW will be a place where diversity is taken for granted and everyone feels at home. If Charleston’s division meets his goals, the UW’s students won’t need him at all. “Our job is to work ourselves out of a job,” he says.

And then some unknown future UW administrator will occupy his office on Bascom Hall’s first floor, wondering who bought the scarred and dainty table, and what it was that this generation thought it knew. •

John Allen is the associate publisher of On Wisconsin. Eric Hamilton contributed additional reporting to this article.

Published in the Spring 2023 issue

Comments

Louis J Jacobs April 17, 2023

This piece was very interesting, thanks for posting it.