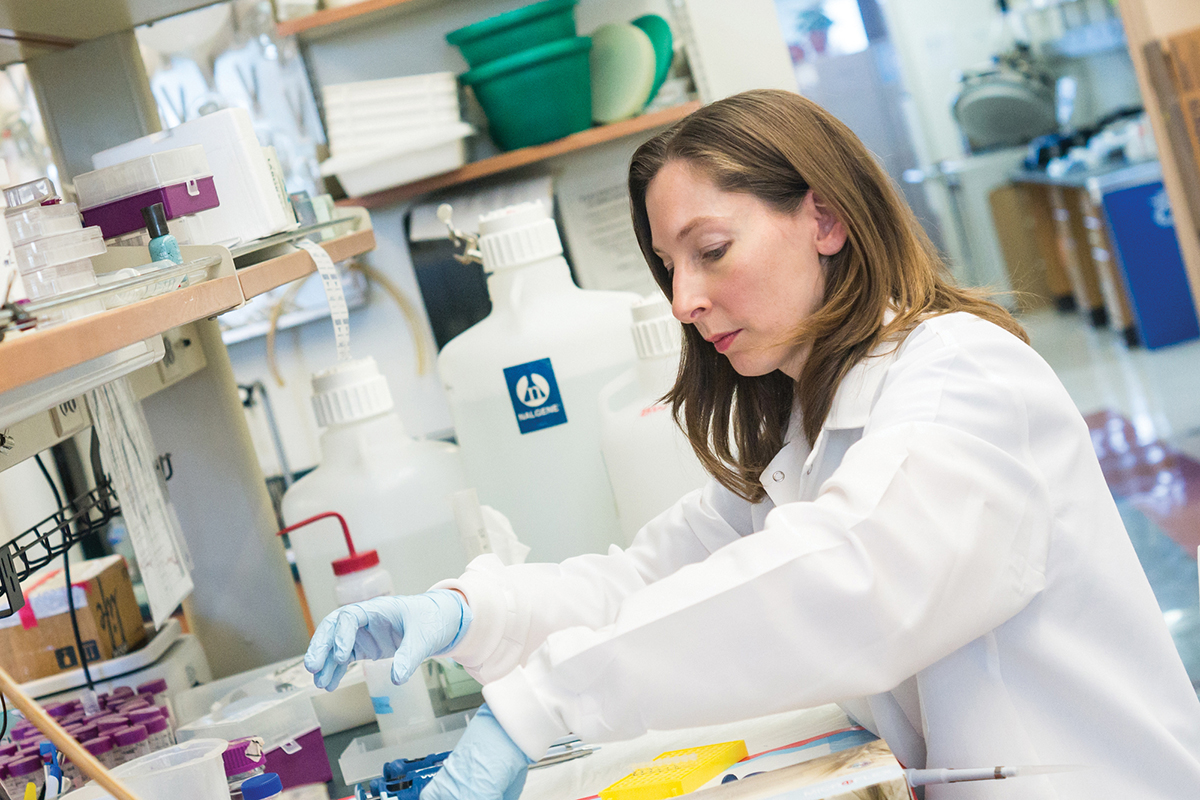

Weaver has uncovered a key feature of breast cancers that could be used to identify which patients are most likely to see success with paclitaxel treatment. John Maniaci/UW Health

Paclitaxel is an old-standby drug in the oncologist’s tool belt. Yet only about half of breast cancer patients treated with it see tumors shrink or disappear, and doctors have no way of knowing which patients will benefit.

But that may soon change.

A team of researchers led by UW–Madison professor of cell and regenerative biology Beth Weaver has uncovered a key feature of breast cancers that renders them either vulnerable or resistant to paclitaxel treatment. And it could be used to help identify which patients are most likely to see success.

“Nearly half of patients who get this drug can be subjected to some pretty substantial side effects without any therapeutic benefit,” says Weaver, a member of the UW Carbone Cancer Center.

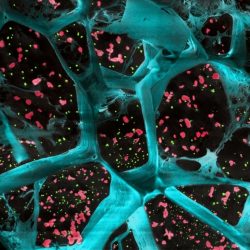

Key to the finding is something called chromosomal instability, found in about half of breast cancers and caused by errors that take place when cells improperly divide. The researchers found that patients with cancers exhibiting high levels of chromosomal instability were more sensitive to paclitaxel and had better tumor suppression, meaning it could be the elusive predictor of success.

“You could measure for chromosomal instability on leftover tissue from a diagnostic biopsy, which patients need to have anyway, and potentially use that tissue for a biomarker test,” Weaver says.

There’s a benefit to trying to teach this old drug some new tricks.

“Paclitaxel is widely used, it’s inexpensive, and clinicians have a ton of experience with it,” Weaver says. “If we could just target it to the right patients, it would be a huge improvement in cancer care.”

Published in the Spring 2022 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.