The Blast That Changed Everything

A 50-year perspective on the Sterling Hall bombing from alumni who lived through it

On the morning of August 24, 1970 — at 3:42 a.m. — an explosion woke a sleeping city, its impact audible for 10 miles.

“Man Dies as Bomb Rips Math Center”

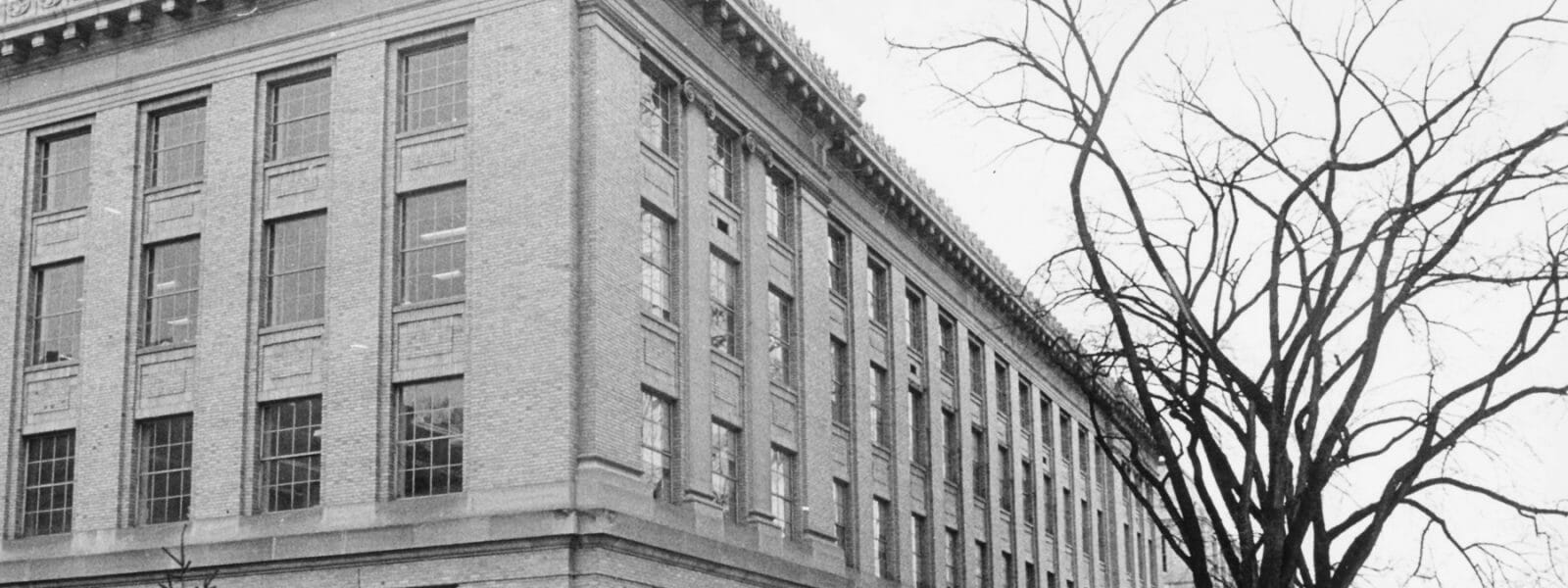

On its front page, the New York Times announced the most destructive act of domestic terrorism the nation had yet seen: the bombing of UW–Madison’s Sterling Hall. It was a shocking culmination of yearslong dissent and despair over the Vietnam War.

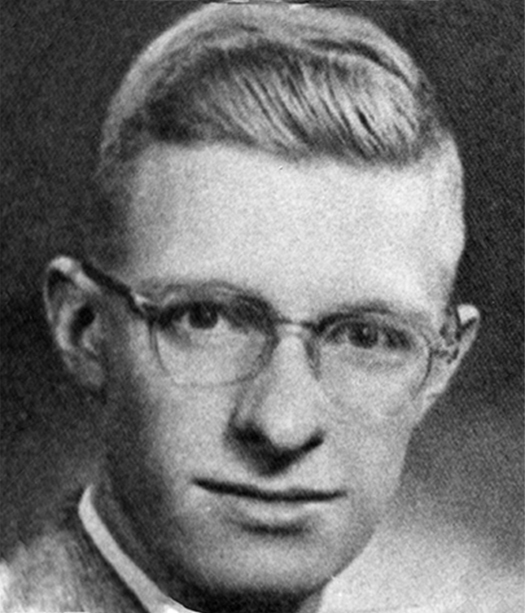

The bomb killed 33-year-old Robert Fassnacht MS’60, PhD’67, a postdoctoral researcher in physics and a father of three young children. It injured four others and damaged 26 buildings, including the old University Hospital across Charter Street.

Four young men, known as the New Year’s Gang, orchestrated the bombing: UW students Leo Burt x’71 and David Fine x’73 and local brothers Karl x’73 and Dwight Armstrong. Their target was the Army Math Research Center (AMRC), located in Sterling Hall and partially funded by the U.S. Army to aid military efforts.

The blast — from homemade explosives stashed in a stolen university van — largely missed the AMRC space but demolished almost everything around it. The four conspirators fled the scene and then the country. The Armstrongs and Fine were eventually caught and sentenced to prison. Burt has remained at large, still a fixture on the FBI’s fugitive list.

By the time of the bombing, protest was a fact of campus life.

Antiwar efforts began in 1965, when some 30 faculty members held a teach-in. In 1967, students rose up against napalm manufacturer Dow Chemical, which was recruiting on campus. Police officers wielded riot sticks and tear gas to forcibly remove them from a campus building. Between 1968 and 1970, protesters firebombed several university offices deemed complicit in the Vietnam conflict. Outrage increased in spring 1970 after National Guard soldiers shot and killed four unarmed Kent State University students during a protest.

Campus demonstrations often embraced civil disobedience, but the Sterling Hall bombing took violence to a new level. The tragic result transformed the UW–Madison peace movement and deeply affected the students who lived through it.

Fifty years later, we wondered how they viewed that seminal experience in their lives. To mark the anniversary, we put out a call for their reminiscences and — not surprisingly — received hundreds of heartfelt responses.

What follows is a representative sample, often painful to read. In stunning detail, alumni describe the physical reverberations of the blast — and its emotional echoes through the campus, the antiwar movement, and the rest of their lives.

Destruction

The sound of the explosion startled the city. When onlookers arrived at the scene, they saw vast damage and tragic loss. In the days after, students who sympathized with the bombers handed out materials justifying the attack, while local officials and FBI agents canvassed the streets. The university issued a $100,000 reward for information leading to the bombers’ capture.

Gregory Schultz ’70

I remember exactly where I was at 3:42 a.m. on Monday, Aug. 24, 1970. I was the lone university telephone operator on duty when the Sterling Hall bomb detonated. I was thrown to the floor by the blast’s enormous impact. Years of dust captured in the ceiling tiles rained down on me like snow as I struggled to answer hundreds of panicked calls that poured in from all over the campus and the city. It seemed like everyone on the planet could only remember one thing: dial 0 — surely the operator will know what the hell’s going on.

Stephanie Twin ’70, MA’72

The night of the Army Math Research Center bombing is one of those things that sticks with you, like the day Kennedy was shot or 9/11. My husband and I were living on Adams Street, a quarter mile from the Army Math Research Center. We experienced — not just heard — an overwhelming and compulsive blast of noise and pressure, like a sonic boom. It blew our locked back door wide open.

Scott Bauman ’71

I heard the explosion and ran out of my State Street apartment expecting to see that someone had hit the state capitol building. I turned and looked up Bascom Hill and saw a huge smoke ring billowing up in the sky. A friend and I drove toward the scene, almost beating the fire trucks. Glass covered the ground in an almost snowflake consistency. As a crowd gathered, I noticed a brown standard-tab file folder that had been blown out of the building so hard it was pierced by a tree branch.

Andrew Volk ’72, MS’74

I went over to the site and found two massive girders holding up the face of the building and men in business suits crawling over the rubble. The glass damage was a stunning show of physics — windows were blown out of the church tower on University Avenue and Van Vleck Hall.

Annette Richter ’70

University Hospital, where I was working as a pharmacy intern, was directly across from Sterling Hall on Charter Street. The horrific blast broke windows and caused cardiac ICU patients to jump out of bed, tearing out their IV lines.

Sally Christiansen ’72

I was asleep in my Langdon Street apartment when my phone rang: University Hospital was pleading with me to come in as soon as possible to help patients injured by the bombing. As a tech pursuing my nursing degree, I was assigned to the ICU and directed to pick glass off of patients.

Berel Lutsky ’73

I was waiting at a bus stop on Regent Street later that morning to go to work. A police car rolled up. Two large policemen got out, grabbed me, and put me in the back of their car. I was searched and questioned. I had not heard about the bombing yet and had no idea why they were so aggressive. As it turns out, I bore a vague resemblance to one of the suspects.

Ann Whelan ’75

I was visiting two blocks away at the Brookwood Co-op. When the bomb exploded, I thought lightning had hit the tree outside and it had fallen into my room. A well-known antiwar activist came in and said, “You are all witnesses I was here.” I went to the scene, where computer punch cards rained from the sky, a sign that research was destroyed.

Michael Averbach ’71

The morning after the explosion, as a member of Students for a Democratic Society, I passed out the famous leaflet in which the bombers defended the action. My roommate and I were stopped on the street by FBI agents and interrogated. Later that night, agents visited our apartment in an attempted roundup of radicals. We decided it was best to go underground and spent the next two weeks hiding out on Madison’s east side.

Dread

The bombing gave students — and their families — second thoughts about the university. Chancellor Edwin Young urged fortitude, telling anxious parents the university was “doing everything possible to provide for the safety” of students. Enrollment dipped 3.3 percent.

Mary Kroul MA’74, PhD’75

I was in Massachusetts for the summer after my first year of graduate studies. When I heard about the Sterling Hall bombing, I felt I couldn’t go back to Madison. I withdrew from the university, and my mother and I rented a U-Haul and removed everything from my apartment. I felt compelled to drive by Sterling Hall and take photos of the blasted-out windows, my mind wandering to the poor researcher who was just doing his work in his lab. I eventually returned to the UW in 1971 to finish my degree.

Larry Hampton ’74

I was planning to attend the University of Delaware, but my sister insisted I go to the University of Wisconsin after a visit to Madison. “It’s you,” she said. I was late putting in my application and was waitlisted. Then news came that a bomb exploded at the UW. The university contacted me soon after and said that they now had room for me.

Katherine Gleiss ’74

I grew up in the small town of Sparta, Wisconsin. UW–Madison was the shaper of intellect and consciousness for my family: parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews, and siblings. I was getting ready to attend the UW when Sterling Hall was bombed. My mother and father were suddenly reluctant, believing the atmosphere to be dangerous and disruptive. My older siblings and other family members convinced my parents that this was the time to stand behind the university that had shaped our family. It was the right decision.

Disorientation

The fall semester started as scheduled on September 21, just weeks after the bombing. Classes were held without disruption — even in parts of Sterling Hall — but reminders of the destruction were all around.

Dan Jaspen ’74, JD’78

My freshman astronomy class was supposed to be held in Sterling Hall. I walked up to the building on the first day of class and was confronted by orange fencing and police tape. My schedule said that’s where I was supposed to be, so I walked around the obstruction, opened the front door, and was greeted by a huge crater. I eventually found the class, but it was quite an introduction to Madison.

Martha (Risberg) Heisel ’74

The bombing affected two of my freshman classes. In Sterling Hall, a computer programming course had plywood covering the window openings. In nearby Lathrop Hall, a water safety instructor course required us to wear something on our feet on the pool deck — for fear there could still be broken glass.

David Hoel ’72, JD’77

I remember sitting in my Chaucer class in Van Vleck Hall, listening to a crew cleaning up broken glass and other debris next door, thinking what a strange juxtaposition of educational experiences it was to be listening to 14th-century poetry in one ear and the aftermath of the bombing in the other.

Lincoln Berland ’71

As a physics major, I saw how profoundly the death of one of our own — Robert Fassnacht — affected the faculty. Among my most vivid memories is seeing one of my professors, who was a faculty adviser for Mr. Fassnacht, break down sobbing during class. That fall, it was as though a blanket had been placed over the entire campus, immobilizing everyone in fear and sadness.

Janice Silver ’73

I was a student tour guide that fall semester, providing commentary as a bus drove visitors around campus. Most people didn’t pay much attention to what I was saying, but when we got to Sterling Hall, everyone stopped talking and got out of their seats to see it. The tourists were from all over the world, and it made me realize that this event was not just local news. Even long before the internet, it had a global effect.

Displacement

Faculty members and graduate students in and near Sterling Hall lost valuable equipment and years’ worth of research. They immediately embarked on a massive cleanup effort, while their colleagues around campus feared for their own materials. Nearly 1,000 faculty members signed a statement condemning the “rising tide of intimidation and violence” and calling for campus to return to order.

George Weller MS’70

I had an office in the physics department on the third floor of Sterling Hall. The day after the bombing, I had to go through FBI checkpoints and one CIA checkpoint to reach my office. Trays of punch cards were full of glass fragments from the broken windows, and my computer station was badly damaged. I couldn’t accomplish much at that time.

Christopher Larson ’71, MD’75

I was working in a microbiology lab on the west campus, and the rules for staying late changed immediately. No one was to be in the laboratories after dark.

Richard Gutkowski PhD’74

I was a reserve officer in the Army Corps of Engineers and pursuing my doctoral degree in structural engineering. For months if not years after the bombing, we took our boxes of work home every night for fear of losing it to protesters.

Gregory Sheehy MD’73

I was doing medical research in the old McArdle building across from Sterling Hall. I found our lab in disarray — glass windows had been blown out, several experiments were lost, and lab rats were running loose. I do not recall much accomplishment during the rest of the summer except for extensive cleanup.

Paul Harkins ’71, MD’75

Several days after the blast, I returned to my lab in the pharmacy school, which faced Sterling Hall. It was blown to pieces. The blast shattered the windows and glassware, the force being so great that some remnants were stuck in the wall across the room. The stone lab counters were cracked and destroyed. I found the jack handle from the truck about six inches into a concrete wall just above my lab station. Anyone in the building at that time would have died or become seriously injured.

Stephen Anderson ’72

My thermodynamics class was held in Sterling Hall and taught by the professor whose laboratory was destroyed and postdoc researcher killed. He brought the class to see what was left of perhaps the top low-temperature physics lab in the world. The largest debris was the size of a basketball. The second-largest was the size of a sugar cube. My professor was profoundly shaken.

Transformation

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, the Daily Cardinal called it both “victory and defeat,” with its editorials in support of the bombers resulting in advertiser boycotts. A year later, Chancellor Young said students were just as politically engaged as ever, though he felt they had backed away from violence. Today, alumni still disagree about whether the bombing was justified, mirroring the debate at the time. Many feel the peace movement on campus was forever changed.

Jean Hoffman ’72, ’90

The world became all too real that day. Campus was a much-changed place from the previous spring. It was as if we all understood the gravity of what our protests could do. This was not a game anymore of breaking windows on State Street or setting fire to garbage cans. A person had died.

John Schooley ’75

On the morning of the first day of classes, I watched students heading up Bascom Hill with a silence — so different from recent first days with protests and rallies. It was deafening.

Linda Zabkowicz Hegg ’73

Fear and hopelessness were the results of that catastrophe. We had marched peacefully, and now we were afraid. When I returned for my sophomore year, the joy of the antiwar movement was gone. Looking back, it is fascinating how one act of senseless violence transformed a national movement.

Jim Adney MA’70

No one wanted to be associated with violence in the defense of peace. The misguided bombing deprived the antiwar movement in Madison of the moral high ground that it had previously maintained.

Lawrence Baron MA’71, PhD’74

About a week after the bombing, I attended an antiwar protest and remember one of the speakers being heckled and blamed for rhetoric that implicitly incited the bombing.

Marysue (Vail) Mastey ’73

The bombing of Sterling Hall directly led me to become an antiwar protester. Even though what they did was stupid and inexcusable, it woke me up. I think it caused a lot of people — not just myself, but others I knew — to focus on the Vietnam War. It forced me to think about the two sides and to pick one.

David Newman ’78

I suspect the dominant narrative from alumni will be that the bombing killed the antiwar movement. But more people were involved in 1972 protests against the mining and new bombing of North Vietnam than were protesting the 1970 Cambodia invasion prior to the bombing. Robert Fassnacht’s death was tragic but one of many.

Donna Jones ’72, JD’78

I was sad and upset that a life was lost unnecessarily. I also was angry and disappointed. I was involved in protests by black students and recalled leaders of the Black Student Strike discussing strategies and deciding not to use any that could take a life. I wondered why whoever caused this didn’t make the same decision. I knew the bombing undoubtedly would hurt all of our causes significantly.

Kenneth Heller ’75

As a Navy veteran who served in Vietnam, I continued to protest the war when I returned to campus. Until Sterling Hall, the antics of the New Year’s Gang were viewed as ineptitude. This changed everything. The protests became fewer and less confrontational. We took to the ballot box, not the streets.

Mary Lynne Donohue ’71, MA’76, JD’79

The day after the Sterling Hall bombing, I left Madison to study abroad in Italy. The campus I came back to a year later was another world: calm, apolitical, unrecognizable. The bomb had killed more than just the young researcher.

Soul-Searching

From guilt to admiration, reaction to the event widely varied. But the mood on campus largely mellowed. The biggest disruption of the fall semester was a food fight in Gordon Commons, according to the book Rads.

Gary Sherman ’70, JD’73

I was consumed with guilt. I had been active in opposing the war, and I knew that, if nobody had been killed, I would have applauded the destruction of a building that was used to plot the death and destruction of other people. I felt that by supporting the more radical elements of the movement, I had contributed to Robert Fassnacht’s death. By the changed tone of the antiwar movement on campus, I knew that many other people shared my feelings.

Barbara Van Horne ’70, MS’72, PhD’79

I was proud to be part of a community raising hell about the lies and destruction of the Vietnam War. It was disheartening to learn that bad policy cannot easily be changed by the people. But the bombing made me feel ashamed. The righteous became as tarnished as the government. I’m sure there was no intention of killing anyone, but using a bomb changed my attitude about protests. I still have no heart for them.

William Draves ’71

The bombing put a guilt trip on a whole generation. One person — yes, I remember his name, his wife, his young children — was accidentally killed by our side as we advocated for peace. But our side saved countless American and Vietnamese lives by stopping the war.

Ann Drinan ’72

This was an antiwar action, the same as so many that took place across the country. That a researcher died is a tragedy, but I’ve always viewed his death as part of the death toll of the Vietnam War.

Pamela Gates ’67, MA’70

I was certainly saddened by the death of Mr. Fassnacht: a terrible loss to his wife, his children, and no doubt to other family members and friends as well. Nevertheless, what the U.S. was doing in Vietnam was unconscionable, and I admired the courage of the Armstrongs and David Fine in bringing that point home. They had no intention of harming any person and felt great grief that their act had resulted in a person’s death. They were trying to stop the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese and of thousands of U.S. soldiers, and for that I admired and continue to admire them.

Al Whitaker ’63, JD’73

I was no stranger to war (the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing, Vietnam 1965, Operation Rolling Thunder), and the blown-out windows, tangled, twisted pieces of metal, and black soot adhering to the gray facade of Sterling Hall bore an uncanny familiarity. I recall thinking, “I’ve seen this before.” I remember being very angry with whoever was responsible for carrying out the cowardly act. I remember thinking of my friends who had lost their lives in battle and thinking, “They deserve better.” And, so too, Mr. Fassnacht.

Reverberations

By 1973, with the suspension of the draft and the withdrawal of troops from Vietnam, the campus experienced no major riots for the first time in nearly a decade. But for many alumni who lived through the bombing, the event had marked a turning point in their lives.

Adrian Ivancevich ’71

By 1970 I was firmly sucked into the leftist antiwar, anti-most-everything cause. I wrote for the Daily Cardinal and participated in every protest I could. The bombing started to fracture my connection with that ideology. The fact that four misguided liberals could transform into violent, bombing, manslaughtering cowards told me that the rabbit hole needed to be plugged. I became a lawyer. I started in criminal defense but finished as a career prosecutor for 33 years, putting away people who did harm to innocent victims.

Steve Fisher ’71

The bombing and killing of a fellow student was a real tragedy that hardened my belief in the rule of law and the need for justice. My family lived next to the Wisconsin assistant attorney general who pursued and caught the cowards who did the bombing. This strengthened my support of strong and proper law enforcement.

Nancy Kaufman ’71, MS’83

What happened August 24 changed my life forever. I was working in University Hospital’s ER while a student nurse. We moved people from the cardiac, ENT surgery recovery, the children’s units. Surgeries had to be redone. I’d seen so much self-destructive behavior in the ER. Sterling was the last straw. I changed my focus from emergency medicine to population health and health policy, where I could improve many lives rather than patch them up one at a time. And I have.

Judith Kleinerman ’73

The FBI came to our house within a day or two because a friend had left his white Ford Econoline in our care — the same type of car that had been used in the bombing. I still regret how arrogant I was with them. I went to medical school and became a hematologist, which routinely brought me in contact with law enforcement. I never forgot how I treated those FBI agents after the bombing, and I never treated anyone in law enforcement like that again.

R. Alan Bates ’72, JD’75

I had been involved in demonstrations on campus and was thinking about my postgraduate future. The Sterling Hall bombing pushed me to decide on law school and seek change by politics and law.

Steven Goldstein PhD’73

My somewhat liberal beliefs and opposition to military action were moderated by this act. The incident encouraged me throughout my life to approach differences in ideology and opinion in a more rational, educated way rather than purely emotionally driven behavior — as should be encouraged by any university community.

Jim Hill ’71, MS’76

I could no longer be a spectator or a “tweener” about the war, or politics in general. So I’ve gradually become much more involved in campaigns, writing letters, and visiting legislators about issues. We do have a system of government that rewards communication and engagement. And in the back of my mind, I’m motivated to do my personal part in avoiding a repeat of events like Sterling Hall.

Preston Schmitt ’14 is a staff writer for On Wisconsin and Doug Erickson writes for University Communications.

Published in the Summer 2020 issue