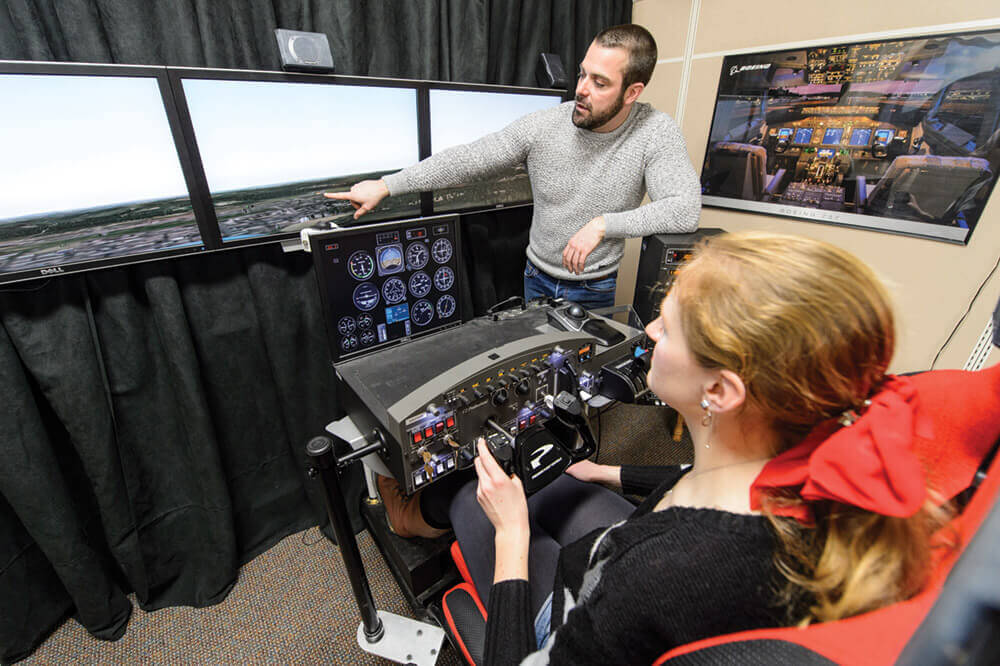

Instructor Chris Johnson walks engineering mechanics and astronautics student Helen Tael x’16 through her first session in a flight simulator used for the UW’s private-pilot course. Photo: Bryce Richter.

Despite the potential distractions — avionics displays, dials, switches, navigational instructions, and more — Dylan Vassar x’16 keeps his focus straight ahead.

In front of him are three computer screens, which together paint a landscape of Madison thousands of feet below. It’s his first lesson in the flight simulator, and, with hands on the yoke — or control stick — all is going smoothly as he cruises over Lake Mendota.

Then he’s told to close his eyes.

Chris Johnson, the certified flight instructor who teaches Introduction to Private Pilot, takes hold of the yoke, flying the plane out of control and plummeting it toward the water.

“Recover,” he says.

With stunning composure, Vassar returns the plane to stable flight in fewer than twenty seconds. Then, Johnson has him practice a few more times, including sometimes with the plane turned upside down.

Each student in the semester-long course, offered for the second time ever at the UW this spring, flew for two and a half hours in the simulator located in the Mechanical Engineering Building. They also met in the classroom three times a week for discussions where — similar to military flight training — Johnson, an Air Force veteran, called on students to answer questions at random.

“To be a pilot, you can’t be shy,” he says. “If you need some information, you need to ask an air-traffic controller for that information, because it could mean your life.”

Most of this year’s students were engineering majors, but there were a few others. By the end of the semester, they completed the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) written exam and were prepared for the oral portion of the practical exam for the private pilot certificate. The first in a series of piloting licenses that permits noncommercial flying, the certificate differentiates these students from other job applicants. Many aspire to become pilots or work for an aerospace company.

Simulator hours also count toward the forty hours of flight time required for certification. Completing those hours and the exam helped cut the cost of flight training — which can add up to $10,000 — by as much as half.

The FAA-approved flight simulator also provides students the chance to “fly” in a variety of weather conditions, something most pilot trainees do not get to experience.

“Pilots get trained in really good weather, but the day they get their license, they can legally fly in weather that they’ve never experienced before,” Johnson says.

During the first two of three simulator sessions, Johnson instructed students on skills including recoveries and how to take off and land. In the final session, they had to fly in bad weather with no help from Johnson. “Some of them crash, but it’s a good way for me to train them what not to do,” he says. “Having that experience early on in life is going to create humble, safe pilots, and they all appreciate it.”

With the aviation industry booming, the class is helping to attract and train much-needed pilots, Johnson says. He hopes to see the private-pilot class extended to a yearlong course, along with adding other aviation classes, such as one that would train students in flying commercial drones.

The class is designed to improve the way pilots are trained and then “publish that to the world,” Johnson says. “Hopefully, people can learn from our successes here.”

Published in the Summer 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.