The Hope Builder

Roberto Rivera’s methods for mentoring others come from a very personal place.

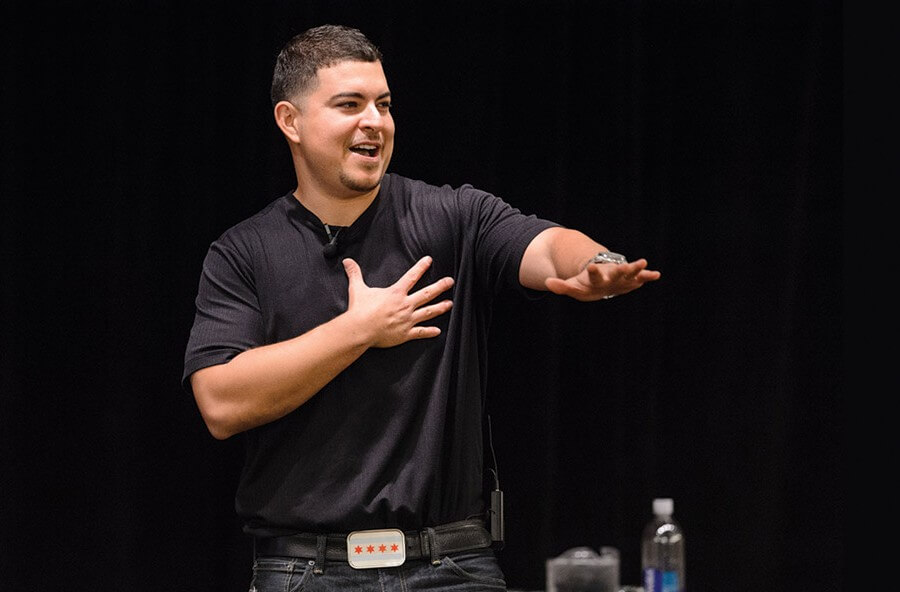

Roberto Rivera ’04 starts many of his speeches with the story of a boy named Carlos.

On this day, a group of Wisconsin educators who run after-school programs listen, transfixed, as Rivera describes how Carlos struggled through childhood. He was labeled as learning disabled in school and was illiterate until the age of ten. At the dawn of his teen years, when his “misdirected entrepreneurial skills” got him kicked out of middle school, Carlos ran away from home and got arrested for selling drugs. At age fourteen, he tried to take his own life. Rivera pauses and asks his audience, “Anyone know a Carlos? A young person struggling to find hope and meaning in their lives?” Heads nod around the room.

Rivera is here because in this age of standardized testing and laser-like focus on core academics, there is little room during the regular school day for teaching young people how to build their social and emotional competency or, as Rivera puts it, how to “turn their pain into propane.” And, he argues, when Carlos learned those skills, he used his pain to find a purpose.

“This is not just the story of any Carlos. See, this is the story of Roberto Carlos Rivera. This is my story,” Rivera reveals. “I went from being a dope dealer to being a hope dealer.”

“I create my destiny. I’m not following anybody’s script, you know?“

Remarkably, Rivera eventually landed on campus, and, as a UW student, he formed the idea that hip-hop music and culture — things that were already part of kids’ lives — could be vehicles not only for self-expression, but also for academic achievement. In 2008, he founded The Good Life, a Chicago-based organization that has trained more than one thousand teachers on how to use tools relevant to young people to spark their interests and engagement, both in the classroom and in their futures. He estimates that more than twenty thousand youth have participated in the program.

Madison Roots

Rivera was born in Madison and spent part of his childhood in the city’s Bayview neighborhood before moving to Galveston, Texas, with his Wisconsin-born mother and his father, who is from Nicaragua. In his late teens, he returned to live with his grandfather and learned that many of the kids he had grown up with in Bayview were trapped in addiction, in jail, or dead.

His grandfather, Floyd Brynelson ’37, LLB’40, a first-generation American who grew up on a farm in Iron Mountain, Michigan, encouraged Rivera to return to school. Brynelson had wanted to attend college when no one else in his hometown was doing so. Years later, Rivera read his grandfather’s old diaries, where he wrote about his dreams for the future. “He couldn’t share [his dreams] with anybody because he felt like the dreams were being attacked,” Rivera says.

That same year, Rivera enrolled at Madison Area Technical College, where he took remedial courses to catch up. During that time, he volunteered at a downtown Madison teen center and worked his way up to program director. While attending a professional-development training session, he met Craig Werner, a UW professor of Afro-American studies who teaches courses on literature, music, and cultural history. The two clicked over a shared interest in African-American music, including hip-hop.

Rivera transferred to the UW in 2002 and enrolled in Werner’s integrated writing course, Critical Thinking and Expression.

“He was hungry to connect his real-world experience with the classroom,” Werner recalls, and the UW gave him time and space to think, and provided distance from more difficult times in Galveston. “He also just needed the complexity of thought.”

One of the course units focused on Shakespeare’s The Tempest. A major theme of the play is struggle, Werner says, including that of Caliban coming to terms with learning the language of his master, Prospero. Rivera responded to the play’s themes and grasped the complexity of Shakespeare’s language while connecting it to hip-hop culture. “He said that Shakespeare had ‘flow,’ ” Werner recalls. “He just was brilliant in everything, and he brought both the intensity of his lived experience and a profound thirst for knowledge.”

Rivera took more courses with Werner, including a multicultural literature class, covering works by writers from a range of racial and ethnic backgrounds, which fueled a desire to devise his own major: social change, youth culture, and arts.

“I think it gave me a greater awareness of my own authorship of my life’s story in a new way,” Rivera says. “I create my destiny. I’m not following anybody’s script, you know?”

Werner guided him through the process of formulating his major, which combined Rivera’s interests in education, teaching methods, and community activism and involvement. The process was not easy, says Werner, who had created his own major as an undergraduate at Colorado College. “They want to fit you into the system, and Roberto doesn’t fit into a system,” he says. “The whole point is changing the system.”

Bridging the Gap

When Rivera talks about hip-hop, he knows audiences and educators are skeptical. Here’s why: if you’re most familiar with the industry of hip-hop, which took off in 1991, you think of it as something used to sell everything from energy drinks to food to cologne. It’s a culture that teaches people to build themselves up at the expense of their communities. But prior to that time, starting in 1971, hip-hop was a vehicle for self-expression and activism, rather than commerce. “Teenagers in the South Bronx realized that they had inherited the legacy of liberation from civil rights,” Rivera explains. “Building up themselves and their communities was their ethic.”

Rivera tackled that divide in his senior thesis at the UW, which he produced as a documentary film, Bridge da Gap. The title referred to the achievement gap in schools and the disproportionate percentage of people of color in U.S. prisons. He interviewed more than three dozen people, including hip-hop pioneers Chuck D, from the group Public Enemy, and Talib Kweli, from the group Black Star, about how hip-hop music and culture can positively or negatively influence young people. “It gave me so much insight to what the problem was and what the potential solutions could be,” he says.

As part of his thesis, Rivera developed an after-school program, recruiting artists in the Madison area to mentor and support young people in learning hip-hop elements such as dance, visual art, poetry, and rap. “We went from doing workshops to doing concerts to doing bona fide, full-on, hip-hop theatrical productions. We got invited to perform at the Kennedy Center,” Rivera says. “But yet, we were amazed and perplexed that students were telling us that they felt like complete failures at school.”

After graduating from the UW, Rivera remained driven by the challenge of creating and cultivating hope among youth. In 2005, his organization, then called Elements of Change, launched a pilot program in a Madison middle school known for fights, gang activity, and drug use to embed the work they were doing after school into the school day.

“Crisis was the precursor for opportunity,” he says.

The program focused on the youth considered the most at risk. But instead of labeling them that way, Rivera told the kids they were being selected for an elite leadership program and gave them this charge: “You all have sparks and things that you’re passionate about — things that you’re good at that have been overlooked. We’re going to take the next ten weeks and help you to find these sparks and fan them into a flame.”

Rivera worked with students in the classroom once a week and met with teachers on other days. He encouraged students to write poems and share what he calls their “blues stories.” Some had parents who were incarcerated and siblings who had been shot. This work stemmed directly from the UW, where Rivera learned from Werner about how hip-hop traces its roots back to blues, gospel, and jazz, which are not the commercial aspects of the music, but its underlying impulses. “What blues allow you to do is affirm your existence. To say that, ‘I matter. I am somebody,’ ” Werner says.

The students took over and emceed the school’s dwindling talent show, performing skits, poetry, and rap songs — and amazing their teachers.

“They wanted to be heard,” Rivera says. And when the program concluded, attendance, behavior, and grades improved among the kids in the four selected classes.

Rivera and some of the students also met with school administrators. One teen said his brother already belonged to a gang, but he was going to take a different path: “Now I realize I have a dream, and I can see how school connects to me wanting to fulfill that dream.”

Another student’s story stopped the room.

“I used to smoke weed every single day after school,” he said, pausing for what Rivera recalls felt like an eternity. “But I don’t do that anymore.”

“What’s different? What do you have now that you didn’t have before?” an administrator asked.

“I have hope,” the student responded.

“What kind of hope do you have?” she asked.

His answer: “This is a hope I’m going to have for the rest of my life.”

Back to School

There is more work to do. While the nation’s high-school graduation rate has reached record highs of 80 percent, the number hovers closer to 50 percent in some of the country’s largest cities. Take a look at our wider world, and it’s hard not to be hopeful about the next generation having empathy and problem-solving in its toolbox alongside math, reading, and critical thinking. By tapping into their emotions, kids connect with their passions and sustain interest in learning, community involvement, and achieving their goals. It turns risky behavior into taking positive risks.

Rivera is now a husband, a father, and, once again, a student. He completed his master’s degree in 2010 at the University of Illinois-Chicago, where he is now enrolled in a PhD program in educational psychology. His focus is social-emotional learning, which teaches kids how to recognize and manage their emotions, handle challenging situations, resolve conflicts, and establish positive relationships.

Rivera’s goal is to demonstrate best practices for teaching these skills, and so he’s digging into research to provide the evidence for the effectiveness of these programs to keep them funded. “I’ve seen so many programs come and go, and so many great things not sustained, so I realize that the research is really a critical element in sustaining good work,” he says. “There are tons of folks doing this hip-hop youth development that are on a shoestring budget. … To have evidence that supports that work is so needed.”

Part of Rivera’s program asks students to take stock of their own strengths, a process that still moves him to tears after witnessing it over the years.

“They stand up, and everyone in class says, ‘My name is X and I am smart at … ,’ and they list one or two things,” he says. “This is probably the first time in their life they’ve ever said their name and that they’re smart at anything, and it’s just so powerful. … The question isn’t what’s wrong with you, the question is what is right with you?”

Rivera calls Werner, his grandfather, and others who have made a difference in his life Michelangelos. The nickname stems from a quote attributed to the famous Italian artist: “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.”

It’s a message Rivera often imparts during his talks to teachers, encouraging them to see the beauty and brilliance in our youth, and helping them to see it in themselves.

“We are all works of art,” he says. “Sometimes the process of getting below the surface is tougher.”

Jenny Price ’96 is senior writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Summer 2015 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.