Story Time

The veterans talk. The volunteers listen. Together they create lasting records of remarkable lives.

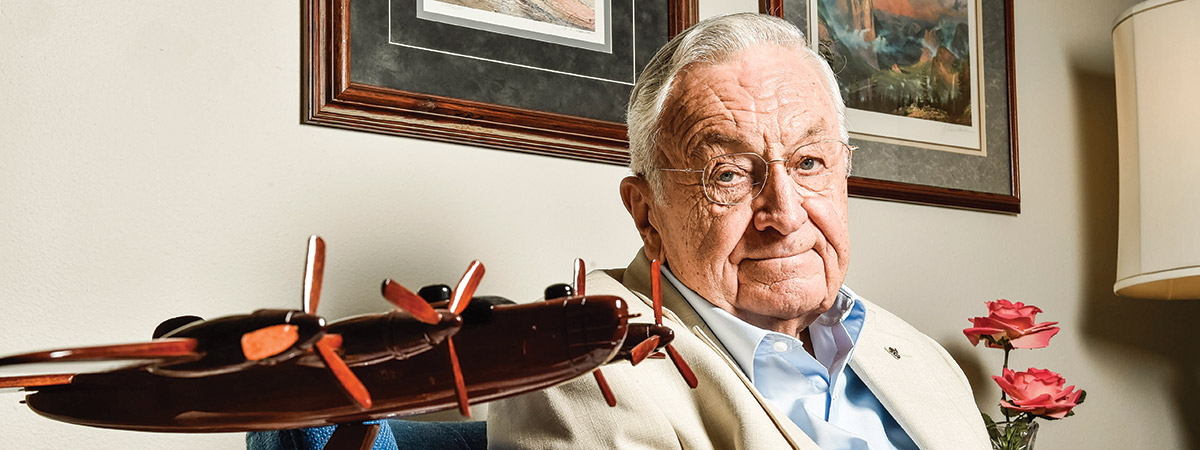

Ellsworth Shields was tired. He was about to climb aboard a B–24 bomber for his fourth mission in six days in the dangerous skies over Germany.

By spring 1945, U.S. bomber crews needed thirty-five missions to earn a ticket home, and this would be Shields’s thirty-fourth. But when a fellow crew member — who needed just one more mission to hit the magic number — asked Shields to switch places, the twenty-year-old Milwaukee man agreed.

“A friend of mine said, ‘Ells, you’ve flown three missions in a row, and I’m trying to get my thirty-fifth. Can I take your place?’ I said, ‘Sure, I need a break,’ ” recalls Shields as he thumbs through the flight journal he maintained throughout the war, keeping track of missions, dates, and close calls.

Combat veterans know intimately how fate and luck are intertwined, and how a seemingly inconsequential decision can have a profound impact. The plane Shields was supposed to fly that day as a radio operator exploded over its target. The entire crew was lost.

Shields, who turned ninety-one last November, doesn’t mind talking about his World War II experiences in the Army Air Corps — even describing the shock and pain of losing friends — but they don’t come up much in casual conversation. And rarely had a nurse or doctor asked him about the war — until a recent hospital visit, that is. He was at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, seeking treatment of hearing problems associated with flying those missions without earplugs, when a volunteer asked him to tell his story. Shields talked about his life and his military service, a conversation that the volunteer crafted into a one-thousand-word narrative.

That encounter was part of the My Life, My Story program started at the Madison VA hospital in 2013. A UW School of Medicine and Public Health psychiatry resident was the first to suggest that asking veterans to tell their life stories would provide a way to get to know patients as more than ill or injured people.

During the program’s first two years, more than five hundred veterans talked to volunteers who then wrote their life stories. All volunteers receive hands-on training in interviewing and writing techniques from program staff. The innovative project quickly drew the attention of other VA medical centers, and in spring 2015, My Life, My Story expanded to six other facilities across the country.

“I think it’s very good if the veterans treat it seriously, which I did. I really opened up,” says Shields, a retired insurance executive who lives in Madison. “They can read it before they operate on me. Anyone who reads this will know I’m a WWII vet. There’s not many of us left.”

Written as first-person narratives, the stories are part of the patient’s chart, easily accessible to medical personnel anywhere within the VA system. According to Thor Ringler ’86, the program’s manager, veterans such as Shields welcome the chance to tell their stories to someone who isn’t treating them as simply a collection of symptoms and medical data, and it helps busy health care providers connect with their patients on a more personal level.

“I think veterans appreciate it when we read their stories, and they always get a kick out of us mentioning it to them,” says Aaron Ho, a second-year internal medicine resident. Ho says he is often surprised by his patients’ stories. Consider the veteran who talked about flying around the country during the Cold War armed with nuclear weapons — but never knowing if they were actual bombs or decoys. Or the veteran who hid his rifle in a barrel of sauerkraut to avoid detection by Nazi troops.

Ho and Matti Asuma ’10, MD’15, who graduated from the UW medical school last May, thought the My Life, My Story program could also provide a valuable learning experience for doctors in training. They suggested creating an elective for fourth-year medical students who would embed in the program, spending two weeks interviewing veterans and writing their stories. The elective kicked off at full capacity during the spring semester, with four medical students enrolled.

Asuma learned about the program while serving a psychiatric rotation at the Madison VA hospital, and he began requesting volunteers to interview his patients. “The great thing with the stories is you have a little window into their lives,” he says. “You learn about patients from a social standpoint.” Asuma, who joined the army right before medical school, is now serving a five-year orthopedic surgery residency in Tacoma, Washington.

Jennifer Sluga ’10, who spent six years in the Wisconsin National Guard, told her interviewer about her childhood and family, her deployment to Kosovo, and her duties in the military. She also talked about being sexually assaulted by a sick-call medic a few weeks into basic training. She hoped that having that experience included in her story would help her health care providers understand why she wants a female physician to perform breast or gynecological exams.

Now, as a psychotherapist who works with veterans, Sluga sees the program as a form of therapy for service members who might never have spoken to anyone about their experiences. It also creates a historical record of narratives from a rapidly dwindling population of veterans of World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

“If anything were ever to happen to me, I would want my family to know there’s this free autobiography I’m leaving behind,” says Sluga. “It’s important to me to let them know that even though there were bad things that happened to me, there were also a lot of good, positive things I got out of the military.”

Interviews usually last an hour. Volunteers are free to ask any questions, although most start by asking the veterans what they would like their caregivers to know about them. Some of the volunteers are UW students enrolled in a literature and medicine class designed for those considering careers in health care. The interviews provide a unique learning opportunity, says Colin Gillis, an associate lecturer who teaches the course, because students learn listening skills and essentially become custodians of the veterans’ stories.

“Most of the students in my class are at the beginning of their lives,” Gillis says. “One of the things we talk about is how narrative is important in finding the meaning of your life. When you’re twenty-one, the narrative you’re making for your life is abstract because it’s all about the future.

“Patients at the VA are usually a lot older than the students,” he adds, “and the way they tell their stories is often in a way the student might not expect.”

Alex Siy x’17 volunteered during Gillis’s class last spring, spending one afternoon each week listening to veterans from every military branch who served in peace and in war. The hardest part for the sophomore neurobiology student was walking into hospital rooms and asking patients to open up about their lives, he says. But once they started talking, Siy was transported to another world.

“The things they said have changed how I look at things. It’s changed who I am,” says Siy, who hopes to become a physician. “Veterans talked about how they view life — that it’s not always the best ride, but [they say], ‘You know what? It’s my life. I own it. It’s who I am, and I wouldn’t change anything that happened.’ ”

Meg Jones ’84 is a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and a freelance writer.

Published in the Spring 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.