Sacred Ground

The long and winding path to Picnic Point includes Madison’s earliest inhabitants.

On July 4, 1864, John Boeringer launched his sailing yacht St. Louis in Lake Mendota. Customers paid twenty-five cents for the round- trip ride to Picnic Point, the site of his dancing hall, where they could indulge in the finest red wine from Missouri and other “wholesome stimulants.” The Wisconsin State Journal lauded the boat as “just the thing for pleasure parties,” and one patron called the destination “as fine a scene of surrounding wood and water as ever greeted a mortal’s eye.”

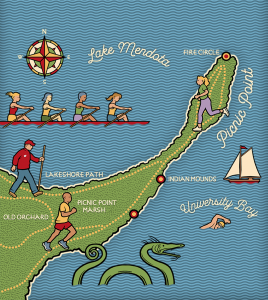

It’s a recommendation that rings through the centuries. Humans have been drawn to Picnic Point for thousands of years. Extending more than a half-mile into Lake Mendota, it’s one of the most recognizable and beloved spaces in Madison and on the UW campus.

“Picnic Point is a cultural landscape that exists in space and time,” says Daniel Einstein MS’95, historic and cultural resources manager for the UW’s Division of Facilities Planning and Management. “If you understand how to read the landscape, you can see the layers of Picnic Point’s story.”

Before glaciation created Lake Mendota, Picnic Point once soared above two stream valleys, a high Cambrian sandstone ridge between the pre-glacial Middleton River and University Bay Creek. As glacial ice advanced southward 1.5 million years ago, hills and bluffs were sheared off right down to the bedrock.

The glacier’s retreat fifteen thousand years ago shaped the landscape of much of the northern United States, opening the land to human settlement as the ice sheets receded and creating Madison’s lakes.

Paleo-Indians settled in the Madison area about thirteen thousand years ago. They lived on the shores of Lake Mendota, and over time left behind projectile points and piles of chipped tools. Native people also likely set fires to keep the peninsula open, as early white settlers described the point as a savanna with scattered trees.

More than one thousand years ago, native people built effigy mounds. There are more in the Madison area than in any place in the world. Six remain on Picnic Point; relic hunters destroyed another. These mounds, writes archaeologist Bob Birmingham, are “detailed maps” of the beliefs and worldview of North American Indians, and they provide a visual reminder of the deep human history on the peninsula.

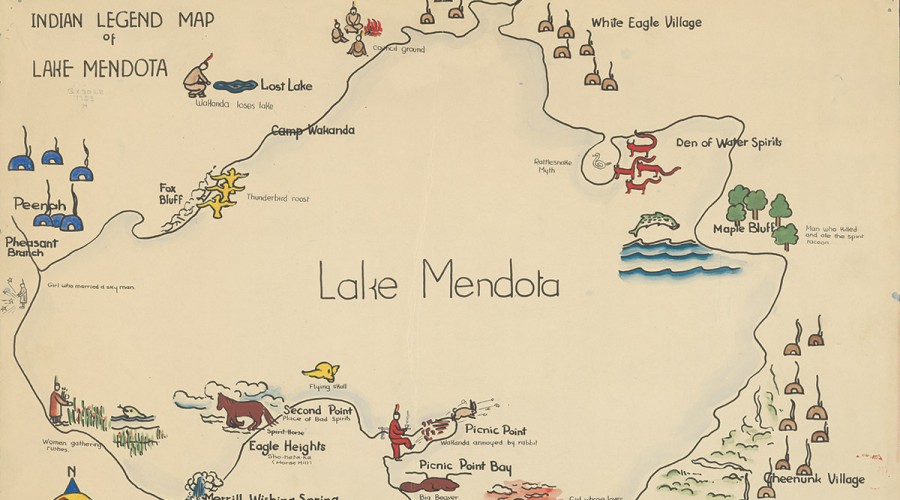

Among other legends, the Ho-Chunk believed a spirit named Waak Tcexi lived in Lake Mendota and overturned canoes. WHS IMAGE ID 85412

One of six effigy mounds that native people built on Picnic Point. Jeff Miller

Several farm families operated dairies on or near Picnic Point; here, two members of a herd graze on the peninsula, circa 1923. UW Archives S12770

The Madison lakes became a major hub of Ho-Chunk activity in the eighteenth century. The tribe called Picnic Point Mo-pah-sayla, or Long Point. The Ho-Chunk expanded southward from their ancestral home around modern-day Green Bay after facing pressure from other tribes and then European explorers. An 1829 Indian agent census counted nearly six hundred people living in villages on all five Madison-area lakes. But hostility from white settlers and the 1832 Black Hawk War forced the Ho-Chunk to cede their land, including Dejope (what they called Madison’s four lakes), and move to reservations. Some, however, refused to move, and others eventually returned to Wisconsin from reservations established first in Iowa, then Minnesota, South Dakota, and finally Nebraska.

White settlers were, by this time, already making inroads. Boeringer’s dancing and dining venture, despite the view and top-tier beverages, didn’t last. By the late 1860s, he sold the property to James Herron, who established a farm with grazing cattle. The land continued to be used for farming into the twentieth century.

The point also became narrower as locks constructed in 1847 to connect Lakes Mendota and Monona, at what is now Tenney Park, raised Lake Mendota water levels. But the spot’s beauty and importance was not lost on residents who visited its shores to picnic and swim, despite private ownership. In 1876, the Madison Democrat made a plea to the city to acquire Picnic Point: “The beautiful point is in reality the most charming spot to be found on either lake. At present it is used as a pasture for cattle, and consequently it is not a neat, safe, or pleasant place for visitors.”

Despite that appeal, Picnic Point would not become a public space for more than a half century.

In 1924, wealthy lumberman Edward Young purchased Picnic Point as a wedding gift for his wife, Alice. He envisioned a sprawling private estate and commissioned a massive stone gate, made of rocks from all over southern Wisconsin, which still stands at Picnic Point’s entrance. Young renovated the simple farmhouse and turned it into a fifteen-room mansion. The Youngs loved horses and established more than five miles of bridle paths, today’s footpaths, throughout the property.

Madisonians continued to venture out to Picnic Point, particularly for romantic rendezvous. Young tolerated visitors and allowed educational field trips to his property, but he employed a caretaker to keep trespassers out. One night, the caretaker came across two students embracing in a state of undress. He marched them back to the house to call the police. According to the caretaker’s notes, the boy told the girl to run. She did. The boy escaped when the caretaker went inside to place his call.

The Youngs lived on their Picnic Point estate until September 1935, when a massive fire destroyed the home. All that remains is a brick walk that led to the side porch. The couple decided not to rebuild.

A place for all seasons: boys splash off the shore on a hot day in 1993. JEFF MILLER

A family enjoys a toasty fire on a brisk autumn night in 2005. JEFF MILLER

Picnic Point’s footpaths were originally intended for horses. Edward Young planned a sprawling private estate with an oval track for horses, stables and pasture, formal gardens, as well as squash and tennis courts. JEFF MILLER

The Young mansion as it burned down in 1935. WHS IMAGE ID 16694

The UW had considered purchasing Picnic Point before, often in the face of development threats. In 1910, word spread that a developer wanted to purchase the land for a subdivision. In the late 1920s, Wisconsin Governor Walter Kohler, an aviation enthusiast, proposed building a base for seaplanes on University Bay. None of these schemes panned out.

In 1939, within days of Young informing them of his decision to sell, the UW Board of Regents secured an option to buy the property through a one-year lease. But the UW was unable to find the necessary donors to make the purchase. Rather than face criticism for spending public money on land instead of academics, UW and city officials proposed turning University Bay into a harbor for boats and constructing buildings, parking, and a road. Outrage from UW faculty halted those plans, and discussions about Picnic Point’s future continued as the property’s value rose.

Finally, the UW negotiated a deal to buy Picnic Point from the Youngs. The sale included a land swap with the UW trading 33.5 acres of Eagle Heights, which had been campus property since 1911, along with a payment of $230,000 for Picnic Point. The UW eventually bought Eagle Heights back from heirs to the Young estate in 1951.

The UW purchase removed the land from active cultivation and led to its transition from farm to forest. And as time goes by, Picnic Point continues to change.

For many years, brush and trees obscured views from the tip of Picnic Point. In 2012, a gift from the estate of Paul R. Ebling ’47, ’52, MD’55 reopened historic views of downtown Madison from the tip, funded the construction of a fire pit and stone gathering circle, and provided easy access to the water.

Only seven years after its acquisition, in 1948, the Wisconsin Alumnus called the “beckoning finger” of Picnic Point “one of the loveliest spots owned by any university anywhere.” But it’s also, as history reminds us, land that could have gotten away.

A bird’s-eye view shows winding stone steps, added in 2012, that give visitors access to the water.JEFF MILLER

Girl Scouts gather in 1950 for a daycamp at Picnic Point. WHS IMAGE ID 66000

Sunrise illuminates a fire pit and stone gathering circle, part of the improvements made to the point’s tip. JEFF MILLER

The massive stone gate from the Young estate still stands today. JEFF MILLER

Erika Janik MA'04, MA'06 is a historian, author, publisher, and radio producer. Her forthcoming book is Pistols and Petticoats: 175 Years of Lady Detectives, in Fact and Fiction.

Published in the Spring 2016 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.