Pigment Prejudice

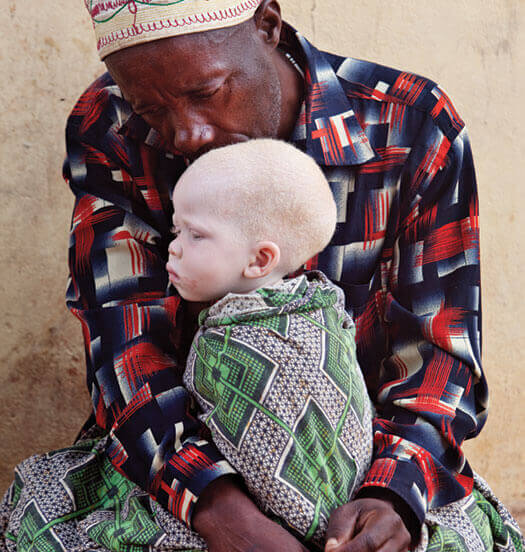

Children with albinism are sometimes hunted in Tanzania and other countries because of superstition that their body parts bring good luck. This father was fortunate to find a job at the government shelter where his son lives, thus allowing him to remain close to the boy.

Two UW alumni are helping children with albinism in Tanzania, where superstition threatens their lives at every turn.

The children feel safe here.

In this simple, six-bedroom center in a village near Lake Victoria in Tanzania, they are not alone. Here a nun and two armed guards watch over the thirty children who share skin as light as their potential fates are dark. Cast off by society and often their own families, these albino children live in dread of bounty hunters and witch doctors, of mutilation and death.

And in their nightly prayers, they include Eric JD’02, LLM’03 and Karene JD’03 Boos. They hope that this Wisconsin couple more than eight thousand miles away can find a way to help them and others like them.

“Dr. Eric and Karene are very compassionate and inspirational people,” says Sister Helena Ntambulwa, who cares for the children. “They normally go and work where other people would not want to go.”

Eric, a philosophy professor at UW-Fond du Lac, and Karene, a physical therapist, have spent nearly twenty years dividing their time between their organic farm outside of Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, and various service projects in Tanzania. In fact, the sole reason they earned law degrees from UW-Madison was so they could help start a law school in Tanzania.

Their latest mission: working with Ntambulwa to turn a ten-acre site on the edge of the Serengeti into a refuge for up to two hundred children with albinism, a genetic condition that affects the pigment of the skin, hair, and eyes. Although it’s difficult to know the exact numbers because so many live in secrecy, albinism is more prevalent in East Africa than anywhere else in the world. As many as 150,000 albinos may live in Tanzania. Karene describes albinism as Tanzania’s modern-day leprosy because of the stigma attached — but while albinos are hated and feared, their flesh comes with a grisly price tag. According to Eric’s research, a single finger from an albino can fetch the equivalent of about $1,300 U.S. dollars, while a complete set of male genitals sells for $32,000.

“To be clear, albinos are hunted and killed,” Eric explains. “There is a network. Witch doctors put a bounty on them, dead or alive, and they cut off their fingers, hands, feet, and genitals. They also take out their internal organs to make potions and medicines. On some occasions, their bodies are skinned, and the skin is used to make talismans that people wear for strength.”

Now Eric and Karene are trying to raise funds for the children’s safe haven in the village of Lamadi. Eric was also recently appointed as advisory counsel to the African Union’s Commission on International Law by the group’s president, Adelardus Kilangi, who is dean of the Tanzanian law school where Eric teaches a few times a year. One of Eric’s first research projects for the commission focuses on developing a context for human rights advances for people with albinism.

“We want to get albinism labeled as a human rights issue,” Eric says. “Then it gets written into the law; then you can write criminal law and statutes and enforcement.” He hopes the African Union will vote on a proposal by January 2014.

Many children in East Africa, where albinism is most prevalent, endure social isolation, living in secrecy for their own safety.

From Tanzania to Bascom Hill

The Booses first moved to East Africa on a lark. They were newly wed and fresh out of Milwaukee’s Marquette University, where Karene earned a physical therapy degree and Eric got his doctorate in philosophy. One of Eric’s former teachers invited them to help build a new college in Morogoro, Tanzania, and the offer was too intriguing to resist. It was 1995, a pivotal time in the country’s history, and Eric and Karene watched in awe as Tanzanians waited for days in the rain to cast their votes in the country’s first democratic, multiparty election. Even after the couple returned to their native Wisconsin, they remained entrenched in various projects, ranging from orphanages to a physical therapy clinic to women’s co-ops, dedicating all of the profits from their farm to support the work in Tanzania.

Sometimes people ask why they don’t focus their volunteer efforts closer to home, but Eric and Karene feel an undeniable pull to Tanzania. Their religious faith is an integral part of their lives, and they believe that their work in Africa is a spiritual calling.

And so they do whatever it takes to answer that call. While in law school at UW-Madison, Eric and Karene juggled work, courses, and their young children, with one often passing off a child to the other before racing across campus to make it to class. They stayed up until 2 a.m. studying every night. The university’s strong African Studies program was a bonus, and they both won Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships so they could learn Swahili.

While they were on campus, Heinz Klug, a native South African and professor of law, was a key mentor. Klug was impressed with the couple’s maturity and commitment to Tanzania.

“To decide to commit to three years to get a JD in order to begin a law school — that’s an extraordinary thing,” Klug says. “You couldn’t do that in the United States, but they understood the conditions in Tanzania.”

A call for help

After their fourth child was born, the couple thought about taking a step back from their volunteer work in Tanzania. Eric started working for a large law firm in Madison, but he quit after a year to resume teaching.

“I realized it just wasn’t who I am,” he says of that experience. “And we couldn’t get Africa out of our blood.”

Then in January 2012, an email arrived from Sister Ntambulwa, whom the Booses had met during their previous work in Africa. She was caring for albino children and other kids with disabilities in the village of Lamadi, she said, and she shared a BBC report that described in gruesome detail the plight of Tanzanians with albinism. The Booses were stunned.

Before heading to Tanzania this winter, the Boos family poses in a field of sudan grass at their farm near Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin. From left are Eric, Zeke, Lauren, Zeb, Meredith, and Karene. Eric and Karene are helping to create a refuge for up to 200 children in Tanzania. Photo: Andy Manis.

“We had been working in Tanzania for fifteen years and had seen albinos, [but] we had no idea that they were slaughtered,” Eric says.

Eric and Karene launched into action. They worked with Ntambulwa on the project proposal to win aid from the Tanzanian government, pledging to build a support network in the United States. Karene set up a 501(c) organization, ZeruZeru, which means albino in Swahili, to help with fundraising for the ten-year, $450,000 project. They also recruited a Tanzanian colleague to draft the project’s construction plans, and Eric helped sink a well and put in a foundation for a dormitory that will house thirty children. Eventually, they hope the campus will be able to accommodate two hundred children.

“It has been a blessing to have this center for the children,” Ntambulwa says. “Still [there are] many, many albino children in the remote villages who need help.”

On Eric’s first visit to the center, he and a fellow professor from Tanzania took breaks from the construction work to visit with the children, chatting with them in Swahili and English.

“We were overwhelmed by their trust and openness,” Eric says. “They talked about what it is like to fear walking down the road, and they never go out alone or at night. They talked about friends they knew who had been abducted and mutilated. They talked about the pain of being rejected and avoided by family and friends … and they also talked about their dreams and goals and love of life.”

At the center, the children receive sunscreen, hats, medicine, nutritious food, education, and physical therapy for those with disabilities. But the greatest benefit is protection.

“It is extremely dangerous to work with albinos,” Karene says, “but justice demands it.”

The danger is one reason why families often feel they cannot care for a child with albinism, Ntambulwa says.

“The albino children live under the threat of being killed at any time by their fellow money-monger Tanzanians,” she says. “So the parents also live with the same fate. … Parents cannot work or do anything productive for their families; they have to stay watching their dear ones not to be killed. Sometimes the killer can kill both the child and a parent.”

Like rabbits’ feet, albino body parts are thought to bring luck in gold mining, fishing, or political elections, Ntambulwa says, adding, “That is why the killing [is] still going on, because it touches some government leaders.”

In the spring, a seven-month-old baby boy narrowly escaped death after villagers chased away attackers and surrounded the house to protect him. The boy and his mother immediately went into hiding, but Ntambulwa hopes to take them in as soon as she can find the room.

Still, she cannot save them all. “In 2011, I turned away a three-year-old boy. He went back with his parents [to] the remote village, and I heard he was killed after a month,” she says. “It was a nightmare, and I felt guilt that I cannot explain.”

A child with albinism enjoys a tender moment with her mother. The child’s father left home immediately after her birth, telling the mother, “You have given birth to a monster.”

The goal of the center in Lamadi is not to segregate children with albinism, but to improve their quality of life until they are no longer so vulnerable.

“We don’t want them to stay there forever,” Eric says. “We need to provide them with a safe haven long enough so they can get an education and integrate into society at higher levels. If you get albino people in the upper echelons of civil service, attitudes will change.”

One Saturday in May, Ntambulwa and the children hosted “Albino Day.” More than one hundred people with albinism, along with local teachers, government officials, and church leaders turned out for a day of festivities and educational speakers. Ntambulwa hoped the event would raise awareness of the issues facing those with albinism.

An ongoing commitment

Eric also tries to raise awareness at St. Augustine University in Mwanza, where he is a visiting professor and teaches during his breaks from UW-Fond du Lac. He started bringing up violence against albinos in his law classes, passing out news articles about the atrocities and talking about it in the context of the U.N.’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“The first night I brought it up [there] was just drop-dead silence,” he says. “It was like nobody wanted to talk about it. And all it took was one student to say, ‘There was this one case in my village’ — and all of a sudden, the floodgates were opened.”

On a recent visit to Tanzania, Eric sought out an interview with Bonifice, a six-foot-five albino business student at St. Augustine. Over lunch at an open-air, thatched-roof restaurant on campus, Bonifice sketched on napkins the genetic permutations that cause albinism and shared his life story. Eric marveled at Bonifice’s deep knowledge of topics ranging from history to economic theories to sustainable farming. “When you cannot go outside in the sun and play with other children,” Bonifice told him humbly, “you tend to read a lot.”

The son of a psychiatrist, Bonifice received a better education than most and didn’t initially realize why his parents never let him go out alone.

This six-year-old child lives separately from her family in a secured shelter built by the government in north Tanzania.

“My schools had a lot of white children, so I never felt out of place,” Bonifice told Eric. “It wasn’t until I noticed that my mother was constantly lathering me up in sunscreen that I became aware of my condition. Then when I took biology in school, I locked on to what it was I had.”

Eric hopes that Bonifice can serve as a role model for younger children with albinism, including those just thirty-five miles away at Ntambulwa’s center. “He has a passion to prove that albinos are no different than anyone else, aside from some little blip in the genetic code, which is inspiring,” Eric says.

In the meantime, Eric and Karene continue to do their own work from afar. Karene and her daughters recently met with renowned scientist and activist Jane Goodall while she was in Madison and she agreed to accept the albino refuge into her Roots & Shoots program, a youth network that promotes causes such as environmental awareness and cultural understanding among diverse groups.

Eric and Karene are also looking forward to taking their four children to Tanzania for a two-month stay this winter, when they will help Ntambulwa and the children set up an organic farm that will include chickens, pigs, goats, and a couple of dairy cows. Although their own farm keeps them rooted in Wisconsin, they’ve considered selling it and moving their family to Tanzania semi-permanently. “We are always prepared to move on short notice,” Eric says.

Left: In addition to being vulnerable to sunburn and skin cancer, those with albinism can also suffer vision problems due to a lack of pigment in their eyes. Sunglasses are a much-needed commodity.

Karene loves the peace and simplicity of life in Tanzania. “When we brought our kids over there, it was a major life lesson,” she says. “That we can get by on beans and rice for two meals a day, with no major toys, no technology, no electricity after 6 p.m. — I loved that simple lifestyle.”

And there’s another reason that pulls her back. “When I’m over there,” she says, “it feels like I’m actually making a difference in the world.”

Nicole Sweeney Etter is a freelance writer and editor in Milwaukee.

Published in the Winter 2013 issue

Comments

Kimberly Gerdes November 15, 2013

Unbelievable story — thank you for sharing.

The Boos family is truly remarkable in their quest to support the children in Tanzania living with albinism. I cannot get the picture of the father with his young son out of my head. I am speechless.

May these children and their families receive the help and love that they truly deserve. And may the Boos family be able to continue their efforts for many years to come.

Josephat Muhoza November 16, 2013

I am Fr. Josephat Muhoza, Eric Boos has been my philosophy teacher at Morogoro. I am now working as Deputy Principal for Finance and Administration at Jordan University in Morogoro. Jordan University is a constituent College of St. Augustine, where Mr. Boos says he works regularly. I have read this article and it gets to my understanding as something probable. Since, I respect Mr. Boos, and I would not doubt his good intentions, I ask anyone who has that possibility, to give me the contacts of Mr. Boos (their e-mail address).I would like to communicate with them urgently, since the Albino project, they say they are helping to fund, has some doubtful descriptins, and its existence seems probable, but not logical! Why would one be allowed to put the albinos together in one place, and therefore facilitate their availability?! Does the Tanzanian government encourage this kind of “help”? Please, let someone connect me to Mr. Boos!

Dr. Eric Boos November 18, 2013

I remember you well, Fr. Josephat,from my teaching days in Morogoro. Your concern is something we all shared at the beginning. Putting all the albino children together in Lamadi village did seem dangerous. But after much consultation with NGOs, Government officials, Mission groups, parents of albino children, those suffering from albinism, and village officials in Lamadi, it was decided that it would be safer to have a safe-haven that was well known with all the locals on board and particularly in a high traffic area for tourists. The logic of the decision was premised on the fact that albino children living at home in small villages are very vulnerable to attack. There is not much protection for them at their homes, and quite often it is their parents (particularly the fathers) who supervise the attacks. And quite often, when they are attacked in their small villages, it doesn’t make the news…thus, allowing this tragedy to go unnoticed. Giving them a safe-haven that will include health care, education and training, and a public image is very important for social change–as opposed to the very suppressed information of random attacks in the outlying areas. Beyond that, it makes it much easier to provide sunscreen, hats, clothes, materials, medication, cancer screening, when they are on a single campus–as opposed to driving all over the 350,000 square miles of Tanzania and addressing individual cases. While we share Fr. Josephat’s concern, it was agreed that this step was necessary to save more children and get information regarding this terrible human rights violation out to the public.

Joann J. Ordille, PhD '93 November 19, 2013

I was very moved by this article. Is there a way online to contribute to helping the albino children, perhaps through ZeruZeru?

Ann Smith November 20, 2013

Is there an organization, with a financial report, to which one can contribute to help these children and to enlarge the facility to house more affected children?????

Thank you.

Niki November 20, 2013

Those who would like to help the Boos in their efforts may make a donation to ZeruZeru. Checks can be made out to ZeruZeru and mailed to:

ZeruZeru

W8430 County Road H

Elkhart Lake, WI 53020

Donations are tax-deductible and will obtain a donation letter as per IRS standards. Questions or comments can be directed to: Boos.karene@gmail.com

Maria Helena November 29, 2013

Fr. Josephat Muhoza,

How could you allow a Devel Spirit to enter your heart, as a catholic priest, called by Jesus, do you want these children and people living with albinism to suffer to the last breath of their lives.

Remember you are now have a wonderful office there in Morogoro. l know you as a Semenarian at Morogoro, and remember where you come from, start with your famly, just with the mercy of God, you do look as you are today. Live Dr. Eric alone and allow the people of goodwill to help the poor and need people, the albinos and those with physical needs in Lamadi Village, Jesus, the Christ Our Lord commanded this.

Do not be a jeoulos priest for the good work of other people.

Maria Helena

Maria Helena November 29, 2013

Fr. Josephat Muhoza,

for your information, there are other centers for the albinos, just people like you do not like to help or preach about them. Our dear goverment yes, want to build a safe heaven hwere these people can be cared and get excellent social servises as you always get from the church dear padri Muhoza!

That is there is no an albino priest, nun, or a catholic brother, get it!

Do you hold on your logic, things logic! But you do not have love from God!

l can’t believe a Tanzanian priest like you Fr. Josephat about the lives of albino in Tanzania; till now you do now what is going on with the horrible life going on in the villages. as long as you do not visit them you can tell all the lies and logic want.

Maria Helena

Mary Nelson December 2, 2013

I want to thank the Boos as well as the alumni magazine for bringing these children into the light of day! I thank you! Mary Nelson

Amy Scherg December 11, 2013

As a former student of Dr. Boos and having met his family. They do exactly what this article suggests. They walk the walk. I applaud their efforts!

Dorothy Schwartz January 18, 2014

I applaud what the Boos family is doing. I would like to be in contact with them; I am on the board of a small NGO which had its origins in involvement with an orphanage in Arusha. (Living Water Childrens Centre). We have expanded but one recent expansion has been to get involved with the issue of protection and education for People with Albinism. There have been some rather encouraging and then disheartening communications with several departments and a school involved with the issue. We have focused in the Arusha area, but also are involved with two schools in Dar es Salaam, and when in Dar last summer met with the staff of the albinism center located at the hospital there.

I am a graduate of UW Madison, 1964, School of Nursing.

Susan Griffin May 3, 2014

Hoping the magazine does a follow up feature!! They need as much public support as possible

Dr. Mark and Molly Druffner August 31, 2014

We work at a hospital in Same, TZ every summer. We live in Hudson, WI and would reay like to connect with you. Please send us your contact information. Asante!

Mary Kelly January 22, 2015

Maybe not thought out on my part, but could these children be adopted in the states?

Thank you for your work with these vulnerable souls. I have learned a great deal from this article. Amazing Grace!

Thank you, Thank you, Thank you!

Madison, Wi