[mis] guided light

A psychopath focuses on a goal — no matter how chilling the consequences. But UW researchers have hopeful news about changing that behavior.

Joe Newman has spent much of his life in a place no one wants to go, studying a group of people who few in his field believe can — or even should — be helped.

For more than thirty years, UW psychology professor Newman has been trying to uncover and understand psychopaths, seeking answers to what is happening in their brains that causes them to be so callous, cold, and calculating.

Psychopaths make up about 1 percent of the general population. But their numbers are closer to 20 percent of male prison inmates — and that’s what initially drew Newman to the UW: he saw a chance to gain unprecedented access behind bars through a faculty member who had contacts in the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

“In most places, it’s impossible to do research in prisons,” Newman says.

But in Wisconsin, the corrections department is a silent, but essential, partner in UW research aimed at discovering brain abnormalities in psychopaths. Newman has worked in the state’s prisons for more than three decades, allowing his team to complete at least eight thousand psychopathy assessments.

Newman’s extraordinary relationship with the prison system and other psychopathy researchers on campus and off has made Wisconsin a leading site for groundbreaking neuroscience research involving inmates. The work is shedding light on the brains of people with psychopathy and building the foundation for what eventually could become a viable treatment for a group of people long considered a lost cause.

“With Joe’s team, the benefits from the actual research are becoming tangible as time goes on,” says Kevin Kallas, mental health director for the Wisconsin Department of Corrections. “It’s refreshing, because the standard line has been that people with psychopathy either can’t be treated or it’s difficult to treat them.”

Why try to help people who lack remorse and might do whatever it takes, including manipulation and violence, to get what they want? That question is one of the hurdles to this work and to getting funding for it. Psychopaths are everywhere in popular culture — in books, movies, and TV shows. But Newman believes that our morbid fascination with them and the conventional notion that they are evil to the core could be what is keeping us from tackling a problem that is not fundamentally different from other mental-health conditions.

It’s not just the general public that recoils from psychopaths. Some researchers have suggested that they are a subspecies of human beings, and that it’s unethical to try to treat them, in case doing so somehow makes them worse.

“When people have trouble controlling their thoughts, like in schizophrenia, or their feelings, like they do in depression, our heart jumps out to them, and we want to understand it. We want to offer them treatment, and it’s a priority to spend mental-health research dollars understanding these problems,” Newman says. “But when it comes to psychopathy, all of a sudden we take our mental-health model and we throw it out the window, and we think of this punitive model, where people are behaving poorly because they’re not motivated or they’re nasty, evil people who don’t deserve our help and need to be punished.”

Newman, the founding president of the Society for the Scientific Study of Psychopathy, and his colleagues are most interested in what causes psychopathic behavior and, more importantly, how they could train a psychopath’s brain to change it for the better.

[fear myths]

Since the 1950s, the most established theory about psychopaths is that their undesirable — and sometimes horrifying — behavior is the result of a low fear IQ. This lack of fear, goes the theory, results in people who don’t worry about being punished for their actions.

Newman has long pursued another theory. He believes that psychopaths are capable of fear, but when they’re focused on a goal, they — for some reason — don’t shift their attention to consider the consequences, such as hurting other people or going to prison. Strong evidence of this extreme lack of attention was demonstrated in one of his earliest studies involving a gambling task. Psychopaths playing the game continued to lose money because they focused on the next card choice rather than on the bottom line.

“If it’s all about callousness, then why is it that they show the same behavioral problems even when the only cost is to themselves?” Newman asks.

When the subjects were made to take a “time-out” to slow down and reflect before choosing, they made better decisions. “[Psychopathy] helps you pay attention to what’s important to you, what’s primary, but it hurts your ability to attend to what’s secondary,” he says.

In a more recent study, Newman and his team used the threat of a weak electric shock to measure fear response, demonstrating how attention can affect psychopaths’ reaction to threat. The researchers put electrodes on the inmates’ fingers, which gave a shock less intense than a static-electricity charge, and then had them view a series of letters on a screen. The inmates were told that shocks might be administered following a red letter, but not after a green one. Because they were instructed to push buttons indicating whether the letters were red or green, the task focused the inmates’ attention directly on the threat, making it primary.

Contrary to the no-fear theory, the psychopaths in the study showed a fear response when they were directly focusing on the threat. But as soon as the task was altered to demand an alternative focus, such as paying attention to whether the letter on a screen was the same as the one that appeared two letters prior, the psychopaths’ fear response disappeared.

Newman calls this an early attention bottleneck, a specific process in the brain that underlies psychopathy. The theory holds up when researchers use brain scans to look at what parts of the brain become more active or “light up” in inmates who are psychopaths, and those who are not, while performing these kinds of tasks. Scans showed that the amygdala, a region located deep within the brain that responds to fear and threats, was activated as much or more so for psychopaths — compared to non-psychopathic inmates — when they were asked to focus on the part of the task linked directly to threat of a shock.

“Once they commit their attention to something, the things that would normally cause the rest of us to stop and update our understanding don’t happen,” Newman says.

This is why the time-out concept works with psychopaths, Newman says, adding that the same approach is effective with children who misbehave in the classroom. “Use the time-outs not just as a punishment, but as an opportunity to reflect meaningfully — that’s what we did with the psychopathic subjects, and it worked,” he says.

This idea clashes with the popular belief that psychopaths are cold-blooded predators who are not motivated to change. Rather, it contends, they are unable to change their behavior because they react differently to the world and can’t process information that isn’t central to their goals.

And that gives Newman and his fellow researchers something most thought was not possible: a target for intervention and treatment.

[brain training]

Today Newman and his UW colleagues are in the middle of a two-year study designed to train psychopaths to shift their attention from their goals to what is going on around them. At the start, Newman and Arielle Baskin-Sommers MS’08, a PhD candidate who is running the study, were not expecting great success. Past efforts to treat psychopaths through traditional means such as group therapy were failures, and some feared the treatment could result in making them more likely to reoffend.

The UW team assessed Wisconsin prison inmates and assigned them to a six-week, one-hour-per-week training regime. Half of the inmates participate in training that matches their condition while the other half go through training that does not. The inmates aren’t told the reason for the training, and they are tested before and after the study to measure changes.

During their training, the inmates play a variety of games. To perform well, much like the gambling task in earlier studies, they must pay attention to cues that are not central to the main goal. In one task, for example, they look at images of faces and are told to press one button if the eyes are looking left and another button if they are looking right. But if the faces look fearful, they are instructed ahead of time to press the opposite button, which requires them to pay attention both to the eye gaze and the expression on the person’s face — something a psychopath normally would not do.

The idea, says Baskin-Sommers, is that “the brain is plastic, and if you train certain pathways that might be weak, you can build up or strengthen those pathways.”

Three groups have gone through the training so far, with encouraging results: when tested on how well they are paying attention to context, psychopaths who were trained in ways specific to their condition showed improvement.

“We’re excited that, in this very first attempt, we’re seeing that kind of change,” Newman says. “We want to move very quickly to testing the limits of how much we can accomplish by combining this new intervention with a more standard treatment to form a more general treatment protocol.”

With an eye on inmates’ lives outside of prison, Baskin-Sommers has developed real-world scripts to share at the end of a task. The scripts explain the skills the study is designed to build and how those skills might help inmates make better decisions. Having completed about four hundred psychopathy interviews in her research, she knows what kinds of scenarios ring true, such as how they could use the skills they’ve learned to help handle battles with drug addiction or deal with friends who frequently cause them to get into trouble.

“We believe that there are mechanisms [we] can train to improve how they react to emotions like fear or to improve thought,” Baskin-Sommers says. “Maybe they will end up still choosing to do the same thing, but at least now they’re thinking about it.”

Newman’s team expects to finish training the remaining inmates in the study by spring 2013. If preliminary results hold up, the researchers hope to attract funding to scan the inmates’ brains before and after training to identify any changes. Down the road, they would like to test inmates weeks and months after their treatment and follow up again after they return to the community.

“I actually feel like we have a better understanding of this mechanism than most other disorders,” Baskin-Sommers says. “I think we’re a lot further along, certainly on the psychopathy front, than [we are with] disorders such as depression or anxiety.”

[mental pictures]

For their work with inmates, Newman and UW psychology professor John Curtin partnered with other researchers trained to do brain scans, including Michael Koenigs ’02, an assistant professor of psychiatry in the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, and UW–Milwaukee psychology professors Christine Larson ’93, MS’99, PhD’03 and Fred Helmstetter. Through a program aimed at promoting research partnerships between the two schools, they won a grant in 2010 to scan inmates’ brains.

But there was one wrinkle. While prisons are convenient places to find psychopaths, the risks and security concerns involved with transporting them from prison to a campus facility for research purposes were deemed too prevalent and too complicated.

Enter Kent Kiehl, a psychology professor from the University of New Mexico. Kiehl, who happened to grow up in the same Tacoma, Washington, neighborhood as serial killer Ted Bundy, solved the problem with a mobile MRI he uses to scan psychopathic inmates in New Mexico prisons for his own research projects. He committed more money to expand the effort in Wisconsin and gather more data; concrete pads have now been installed at medium-security Fox Lake and Oshkosh correctional institutions for parking the semi-trailer that carries the scanner.

Since acquiring the scanner five years ago, Kiehl has used it to collaborate with other top psychopathy researchers around the country, giving them access to scans and populating his own research with more inmate data. “They can answer their questions, and I can answer my questions,” Kiehl says.

Newman’s track record with state prisons also paved the way for the arrangement in Wisconsin, says the Department of Corrections’ Kallas. “He’s been in the prisons for so long, and his research has gone so smoothly, that members of the department could feel good about going these extra steps and allowing an MRI imager within the perimeter of the prison,” he says.

Baskin-Sommers says that the inmates take their voluntary participation seriously. One study participant, she recalls, wrote a note that read, “I’m going to miss my appointment. Can you reschedule it?”

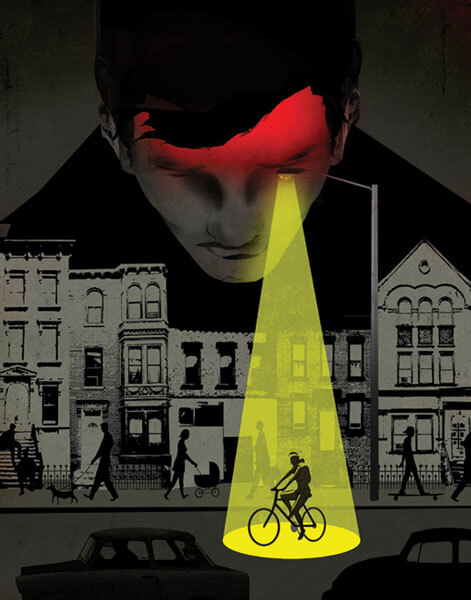

UW researchers are exploring what’s happening in the psychopathic brain and whether psychopaths can learn to shift attention from their goals to what’s going on in the world around them. The research is based on plasticity — the notion that, with training, critical pathways in the brain can be strengthened. Brian Stauffer.

[an unexpected path]

Prison is not the place Koenigs expected his research to take him when he began studying patients with brain injuries as a neuroscience graduate student at the University of Iowa. He was fascinated by cases of patients who didn’t lose motor function, language, or memory, but did experience a striking change in personality.

His work focuses on the part of the brain located above and between the eyes, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and how damage to it affects social behavior, emotion regulation, and decision-making.

On the wall of Koenigs’s office in University Research Park on Madison’s west side hangs an artistic rendering of a skull with a metal rod going through the frontal lobe. The unsettling and intriguing image — created for Koenigs by his sister-in-law, a graphic designer — is a nod to Phineas Gage, the most famous case in neuroscience. Gage was a foreman on a Vermont railroad crew in the 1800s when a freak accident sent a four-foot-long metal rod blasting through his face and out the top of his skull.

“He survived with virtually no motor or sensory impairment, and never lost consciousness, even though he had this gaping hole through the front of his brain,” Koenigs says. But Gage was so “radically changed” after the accident, according to the doctor who treated him, that friends said he was no longer himself and his employer would not take him back.

“He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows,” the doctor reported.

These kinds of brain injuries don’t turn patients into psychopaths — they don’t go out and engage in criminal behavior — but they resemble them on one key point. “They seem not to care as much about the feelings of other people,” Koenigs says.

That behavior sparked Koenigs’s interest in psychopaths and motivated him to learn more about dysfunction in that part of the brain and how it might explain why psychopaths do the things they do. He knew about Newman’s work when he first came to the UW four years ago, and the two started talking and comparing notes. Koenigs asked Newman, “What’s a psychopath really like?” Newman, in turn, asked, “What are these frontal-lobe patients really like?”

Those initial conversations led to joint research projects in Wisconsin prisons. So far, their work has shown that psychopaths’ decision-making is similar to that of patients with damage to the frontal lobe: both are less able to control their frustration, and both act irrationally more often. And in a follow-up study, using the mobile scanner, they found that in psychopaths the connection is weaker between the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, two parts of the brain involved in empathy, fear, and decision-making.

“These areas aren’t communicating with each other to the same degree that they do in the non-psychopathic brain,” Koenigs says. “This was exactly the kind of thing I hoped to find.”

Kiehl has been studying psychopaths for two decades and scanning inmates since 1994. He believes the more brain scans researchers can do, the more they will come to understand. Staying on prison grounds, where they can do as many as eight scans a day, allows researchers to study a population size that wouldn’t be possible if inmates had to be transported from prisons and back again.

“There’s really no end to the number of [scans] I’d like to collect,” Kiehl says. “I don’t really see a moment where I say, ‘I’m done.’ ”

[the bottom line]

Evidence-based treatments for people with psychopathy would be a huge benefit to states, since many have doubled their prison populations in the last decade or so, Kiehl says. He estimates that the national cost of psychopathy is ten times the cost of depression, amounting to $460 billion a year. A main reason for the difference is that psychopaths get arrested frequently.

“I’m not a bleeding-heart liberal about this stuff … [but if you] take these high-risk guys, put them in appropriate treatment, and do the best you can, everyone benefits. We all benefit economically; we all benefit because they won’t come back to prison,” he says. “That’s what we all want, but you can’t just have a tacit kind of, ‘They should just get better because they should.’ You have to help them.”

Kiehl points to the efforts of Michael Caldwell, a lecturer in the UW psychology department who also serves as senior staff psychologist at the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Facility in Madison. The young patients there, ages thirteen to seventeen, are among the most violent in the juvenile corrections system, and many display substantial psychopathic traits, including extreme callousness and lack of empathy.

“They don’t understand why you would not use a gun to get a basketball if you could have just asked the person,” Caldwell says. “They don’t really see the difference.”

Caldwell and the staff employ intensive, lengthy individual and group therapy, along with a rewards-based system in which patients earn privileges for relatively short periods of good behavior. The offenders who end up at Mendota have typically responded to punishments or sanctions with more violent and illegal behavior, so this method is aimed at breaking that cycle. The center was established in 1995, and part of its mandate from the state was to study the effectiveness of its treatments.At the start, Caldwell admits, he was somewhat skeptical.

“The research on treating kids who are this severely criminal in a secured corrections setting was pretty dismal,” he says.

Yet their methods worked. In one study, Caldwell followed up with two groups of potential psychopaths: 101 had been treated at Mendota, and another 101 received less-intensive, conventional treatment in juvenile prisons. About half of each group had hospitalized or killed someone prior to being confined.

But after their release, none of the offenders treated at Mendota were charged with murder, while those in the control group went on to kill sixteen people over time. And in the two years following their release, youths who had been treated at Mendota committed half as much community violence overall as those in the other group. The result is a program that saves $7 for every $1 invested.

Caldwell and his team initially hoped that the effort would — at most — achieve patients who fought less with staff and had an easier time adjusting to the treatment center, which would keep their confinement from being extended. So when the results were in, he couldn’t quite believe them. He devoted two years to checking his data with other researchers, making sure he had not made some kind of mistake.

“It seemed to work the way we had planned it to work,” he says. “Even though when we were planning it, I think we all thought, ‘Well, this is the best Hail Mary pass, but realistically, it’s not very logical.’ ”

The treatment program doesn’t focus on empathy. It goes in the opposite direction, with staff working to change the young men’s behavior first, then starting to see changes in their basic character downstream — what Caldwell calls “going through the back door.”

“The best way to treat them may not have that much to do with what’s the core central feature [of psychopathy],” he says.

Are there people in the field who think it’s already too late for kids like these? “Oh, yeah,” Caldwell answers, “there are lots of them.”

[interview with a psychopath]

Just a few days earlier, Caldwell evaluated a teenager who, despite facing sixty years in prison, was grandiose and self-centered — key markers of psychopathy. He thought his moods controlled the weather.

“Do you think you have any personal problems at all?” Caldwell asked the boy.

“No, not at all. I’m perfect,” he replied, adding that he was more intelligent than the police who arrested him and the judge presiding over his case, even though he scored 80 on an IQ test.

While people throw around the “psycho” label in casual conversation to label a variety of actions and behaviors that don’t come close to the real thing, there is an established practice for identification. Experts such as Caldwell do interviews to assess whether someone is a psychopath, using a test devised by Canadian researcher Robert Hare. Hare’s checklist of twenty criteria covers antisocial behaviors including impulsivity and sexual promiscuity, and emotional traits including pathological lying, superficial charm, and lack of remorse or guilt.

Koenigs says that absence of emotions was the most striking for him when he first began to speak with psychopathic inmates in prison.

“Non-psychopathic inmates, if they’re talking about how they have a daughter they haven’t seen in years, you can see that it bothers them that they’re in there. … In psychopathic prisoners, in some respects, that’s the most revealing part of the interview — that they seem not to have these connections,” he says.

After the interview, researchers also review other official records, such as court and police reports. “We’ve had these experiences where we conduct a full interview, we think this person is this really nice person who’s had this particular life experience — and then we open their file,” Newman says.

In one inmate’s case, his only truthful response was to the first question asked: “What are you like as a person?” His response? “I am a chronic liar.”

Psychopaths are not all the same. The condition is a complex and heterogeneous cluster of symptoms, and it has enough variability to suggest there may be subtypes. This is another area of research the UW team is pursuing.

Hare’s checklist allows for a score of 0, 1, or 2 for twenty different traits. A 30 is the threshold for being psychopathic. But as Koenigs notes, “There are a lot of different ways you get to 30. More subjects would help us disentangle psychopathy from other related issues — [for example], antisocial personality disorder, violent and aggressive tendencies,” he continues. “The more prisoners we can scan, the better able we’ll be to disentangle this complex interplay of issues.”

That remains a possibility, as long as Newman and his research partners can maintain their good relationship with state corrections officials — something they have done during multiple administrations from both parties, thanks to the trust they’ve built over the years.

“They’re optimistic and interested in it,” Newman says. “There’s a long history of prisons being these kind of dead places with people who are not motivated by science [or] by helping people who are in the prisons. And what we see is an agency that says, ‘Learn some more, tell us about it.’ ”

As compelling as the financial arguments are for devoting more research dollars to studying psychopaths, Newman remains dedicated to changing public perception, too. That’s a tall order — perhaps as tall as finding answers to the questions that guide his work.

“It’s one thing to talk about these adult psychopaths who do these horrible things,” Newman says. “It’s another thing to talk about a five-year-old child who seems to have these traits, and he or she has a whole life ahead. … What could we do for them that would change the way they process information that would lead them down a different path? That has been my question for thirty years.”

Jenny Price ’96 is senior writer for On Wisconsin.

Published in the Fall 2012 issue

Comments

Christine Meulemans September 22, 2012

What a valuable piece of information! There is so much more work to be done on the workings of the frontal lobe. I see it in my spouse with a fronto-temporal degeneration diagnosis who was standing next to a choking woman and said, “Well let’s go now”. I see it in my autistic grandson who says,”Is this an angry face?” And I see it in my adopted neice who has begun punching teachers in school wnen frustrated. With more study on the workings of the brain, there may yet be hope.

splashy September 23, 2012

I’m thinking that sometimes being beaten could lead to this kind of problem too, because the head is often where people hit others, and if it’s a child that is hit then it could lead to this.

In some ways it sounds like it’s somewhat the opposite of ADHD, an possibly related to obsessive compulsive disorder.

David Gage October 17, 2012

“The result is a program that saves $7 for every $1 invested.”

Data like that’s hard to ignore! Hopefully, our state, and others, will begin seeing the financial benefits of an ounce of prevention. Of course, it’s not just the financial savings. What a difference it must make in these people’s lives when they feel more control over their actions.

David Gage, Ph.D.

B.S. ’76, Psychology, UW-Madison

Diana October 23, 2012

Hard to ignore? Even harder to verify.

I’m always interested in knowing who designs these experiments, and what kind of consent these people give. And — how much grant money is involved.

Murphy van Benschoten October 23, 2012

Frontal lobe research should rank high in studying behavioral maladies. The more I read the more I see the frontal lobe as the location in the brain that is the responsible area for the deviations from “normal” behavior.

A deviation can come from the response to hit on the head or a chemical imbalance with which you were born. Regardless of the way the frontal lobe has deviated that individual from the “norm” we need to focus more studies on the brain. Becoming much better acquainted with our brains and how different areas of same effect our lives.

Thank you

Diane October 23, 2012

This article makes me want to take Pro. Newman’s class even more! How lucky we are to have such supportive agencies around campus. I really believe plasticity can lead to a successful tx.

Lynn Edlefson October 24, 2012

Another great work from Jenny Price. I wonder if a second article could focus on early attachment?

DIANA (not Diane) October 25, 2012

Have these experimental subjects given consent? Where does the financial support come from for these experiments?

Laura October 29, 2012

I applaud any effort to debunk ‘evil’ as a legitimate explanation for behavior. Any application I’ve seen hinges on the assessment (assumption) that the person is ‘otherwise normal’. From young ages, people are punished for differences no one really understands. Prison is where you will find a lot of society’s failures to understand and help its citizens.

Hugh Schmidt December 16, 2012

This gives some helpful insight to explain behavior we see on “I hate [animals]” Facebook pages. They flurry like a screeching mass of feral cats whenever anyone raises a concern about the intent or impact of their pages.

Lyn December 19, 2012

Dr. N. Campbell-McBride suggests that many psychopathic tendencies can be reversed by healing the gut (google Gut and Psychology Syndrome, or GAPS). Simple and unsuspecting, but very compelling. The research has already been done. GAPS is the key to helping these people.

Henry Baldwin January 25, 2013

The treatment program doesn’t focus on empathy. It goes in the opposite direction, with staff working to change the young men’s behavior first, then starting to see changes in their basic character downstream — what Caldwell calls “going through the back door.”

Has Joe Newman checked into the upbringing of his subjects to see if they were raised under conditions of Permissive parents, undisciplined, self-centered, no or little parent bonding?

It appears that his subjects need childhood Behavior training starting from the day they were born in discipline, self-centeredness, (the world doesn’t revolve around then), and parental bonding for emotions for other people.

Henry

A reply from Joe Newman is requested.