Empty Nests

“We grieve because no living man will see again the onrushing phalanx of victorious birds, sweeping a path for spring across the March skies, chasing the defeated winter from all the woods and prairies of Wisconsin.”

Aldo Leopold in 1947

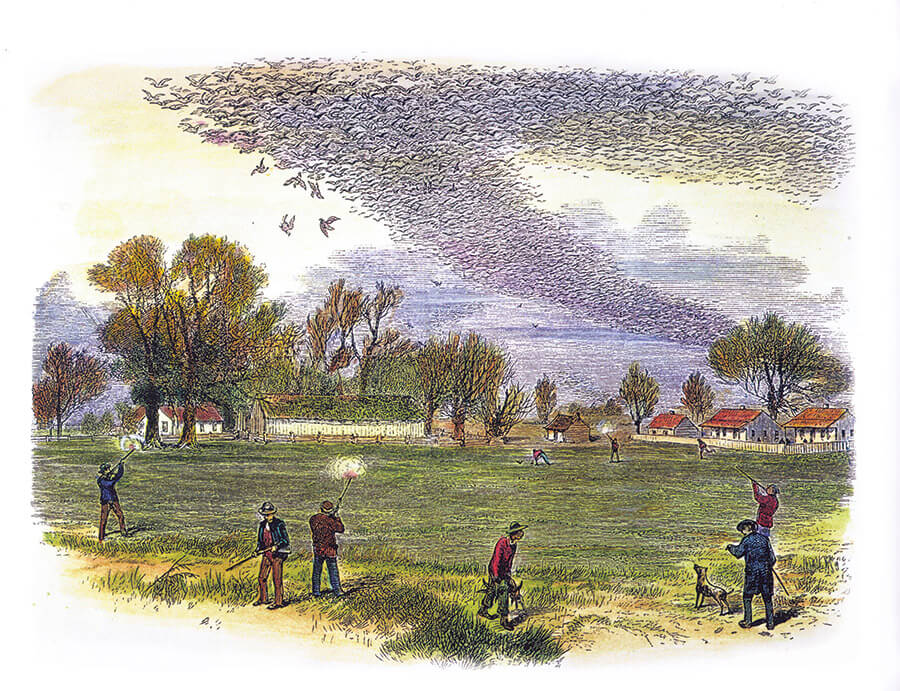

In a scene common in the mid-1800s, hunters aim at enormous flocks, bringing down passenger pigeons that they then sold to urban markets. Courtesy of Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.

Wisconsin conservationists commemorate the passenger pigeons that once darkened our skies.

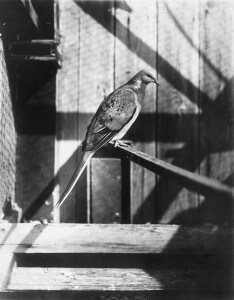

One hundred years ago, a passenger pigeon named Martha died in a Cincinnati zoo. If she had been lonely, it was for good reason: She was the sole survivor of a species that had declined from several billion to one in half a century.

And then on September 1, 1914, there were none. Martha’s death was the last act in a most astonishing conservation tragedy.

One hundred and fifty years before Martha’s death, immense flocks of passenger pigeons had darkened the skies across eastern North America as they sought the sporadic heavy crops of nuts on oak and beech trees. Then, starting in the mid-1800s, thousands of hunters shot and netted the birds, selling them to urban markets hungry for meat.

The pigeons’ habit of gathering in huge numbers was handy for the pigeoners, if not for the pigeons.

Huge scarcely does the phenomenon justice. In 1871, during one of the largest assemblies of passenger pigeons ever recorded, hundreds of millions of pigeons nested across 850 square miles of central Wisconsin north and west of the Wisconsin Dells. Eyewitnesses reported that almost every tree held dozens of nests.

“It’s still hard to get your head around that,” says Stanley Temple, a UW professor emeritus of forest and wildlife ecology and a noted ornithologist. “It’s mind-boggling to think of that kind of abundance being wiped out in less than half a century, but it happened.”

Hunters killed pigeons by the millions and sent thousands of barrels of birds to cities in the East and Midwest by rail.

By 1909, the American Ornithologists’ Union offered a $2,220 reward for a live, wild passenger pigeon. It never spent the money.

The passenger pigeon evolved and thrived in the deciduous forests of the eastern half of North America. Its closest living relative is the band-tailed pigeon of southwestern North America, and it is only distantly related to the rock dove or common pigeon (the domesticated varieties of which are often called carrier pigeons or homing pigeons).

A century after Martha’s demise, scientists, historians, artists, and educators from Wisconsin and elsewhere have mounted Project Passenger Pigeon, a yearlong effort to remember the bird and then apply the lessons of its abrupt extinction to today.

“This is not a happy anniversary,” says environmental historian Curt Meine

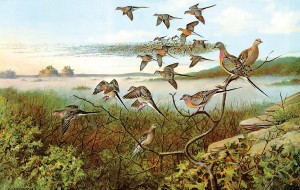

Once upon a time, passenger pigeons occurred in enormous numbers — hundreds of millions in central Wisconsin alone in the 1870s. This year, a century after the very last bird died in captivity, Project Passenger Pigeon is calling attention to the species and the lessons we can learn from its extinction. Courtesy of Anne Marie Gromme/Artbarbarians.com

MS’83, PhD’88, an adjunct professor of forest and wildlife ecology who, along with Temple, is one of the project’s organizers. “But we want to acquaint people in North America and beyond with the history of the passenger pigeon’s demise, and broaden that to look at how human activity affects other species. We want to motivate people to take actions to promote biodiversity today and in the future.”

Project Passenger Pigeon includes science, art, education, and music, says Temple. “This is a teachable moment about extinction, especially when it’s caused by overkill, which unfortunately still goes on. Wisconsin is knee deep in the story of the passenger pigeon — from the vast flocks that used to frequent our state, to the scientists who studied and celebrated them,” adds Temple, who has been lecturing about the pigeon around the country.

Three scientists closely associated with UW–Madison played pivotal roles in keeping the pigeon’s memory alive:

- Arlie William Schorger, a UW adjunct professor of wildlife management from 1951 to 1971, wrote a book about the pigeon in 1955. “Bill Schorger was Wisconsin’s best natural historian,” says Temple. “He never saw a live passenger pigeon, but he doggedly unearthed thousands of early records of the pigeon in Wisconsin and elsewhere, and used them to reconstruct the pigeon’s story.”

- Conservationist and author Aldo Leopold, founder of what is now the forest and wildlife ecology department, eulogized the pigeon when the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology erected a monument to the bird at Wisconsin’s Wyalusing State Park in 1947: “We have erected a monument to commemorate the funeral of a species. It symbolizes our sorrow. We grieve because no living man will see again the onrushing phalanx of victorious birds, sweeping a path for spring across the March skies, chasing the defeated winter from all the woods and prairies of Wisconsin.” The remarks were included in Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac, one of the most influential nature books ever published.

- David Blockstein ’78, a UW postdoctoral fellow in 1986–87, wrote the definitive description of the passenger pigeon for The Birds of North America. Blockstein, a senior scientist with the National Council for Science and the Environment and another leader of the centennial effort, acknowledges that vast flocks of hungry pigeons were a mixed blessing to the pioneers: “We read accounts about women and children rushing inside in a panic, as hordes of passenger pigeons flew overhead. But for the most part, that was good news, because it meant fresh meat; they were flying low enough that you could just swing a long stick and get some pigeons.”

The industrial slaughter by pigeoners was another matter, however, aided as it was by the telegraph, which helped pinpoint the continually moving game. Still, how could they kill every last pigeon? Blockstein says that wasn’t necessary, because hunting also affected reproduction.

“The pigeons were colonial nesters,” he explains, “but over a few decades, every time they tried to nest, the nesting ground became a killing zone, and they abandoned the nests.” At the same time, the destruction of the forests in eastern North America cut into the bird’s habitat.

Blockstein says this year’s commemoration is less about mourning the past than preventing a rerun. “The pigeons’ story makes visceral connections: people try to comprehend these phenomenally large flocks, and then recognize that the birds will never again exist,” he says. “It’s a story about how we have changed the world with our technology and numbers — and not always for the better.”

A cagemate of Martha, the last surviving passenger pigeon, is shown in this photograph taken in the late 1800s. Researchers are almost certain that Martha was born in Wisconsin, but she ultimately died in a Cincinnati zoo in 1914, bringing to a close an astounding story of abundance and extinction in America’s history. Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society 53459

We couldn’t do that again, could we? Yes, says Temple, who notes a parallel with some marine fisheries today. “We should be past this, but we are wiping out fish like the bluefin tuna, the menhaden, and the cod. We are doing to them exactly what we did to the passenger pigeon.”

It shows our modern bias to ask why hunters continued hunting, even as the pigeon flocks dwindled, says Blockstein. “People had no experience with a species being numerous and becoming scarce in a couple of decades,” he says. “Now, unfortunately, we grew up knowing about endangered species and extinction; these are part of the landscape we live in.”

In his eulogy — written less than four decades after the extinction of the passenger pigeon — Leopold eloquently captured the loss in terms that resonate to this day:

Men still live who, in their youth, remember pigeons. Trees still live who, in their youth, were shaken by a living wind. But a decade hence only the oldest oaks will remember, and at long last only the hills will know.

David J. Tenenbaum MA’86 writes for The Why Files (whyfiles.org) and covers research for University Communications.

Published in the Summer 2014 issue

Comments

francine flambeau July 8, 2014

Great story. However, I could not get the link for Project Passenger Pigeon to work.

Mary Hoddy July 11, 2014

There is a life size bronze of Martha in The Roost at Union South. I feel sad each time I see her and recommit myself to telling her story to visitors. It’s one small way I can help people connect to Aldo Leopold and understand how we impact our environment.

tim July 11, 2014

This article is supreme.

John N. Englesby July 11, 2014

I’m from Augusta, WI, originally, I hate to admit in connection with the extinction of the passenger pigeon, as one of the largest nestings & massacres ever took place near Augusta, located just inside the SE corner of Eau Claire County. That fact was noted some years ago in a roadside monument at a rest stop along I94 going north, but I noticed sometime later that the reference to Augusta and the mass murder had been removed…

Carol Sibley October 2, 2014

“One Came Home” by Amy Timberlake is a 2013 children’s book that winds its plot around the passenger pigeons in WI in 1871. It is a very good read for adults, too.

fflambeau October 29, 2014

Link to Project Passenger Pigeon does not work! Otherwise, nice story.

Laurie Solchenberger October 30, 2014

A 4th/5th grade class at Lincoln Elementary School in Madison, WI, is commemorating the Passenger Pigeon’s extinction by including the Passenger Pigeon in our study WI this year. We hope to also make a connection between this extinction and our market-based/consumer-driven economy. Many Lincoln classes are participating in the foldtheflock.org project. Grateful for those people who continue to keep the memory of the Passenger Pigeon alive.