Can You Nurture Your Nature ?

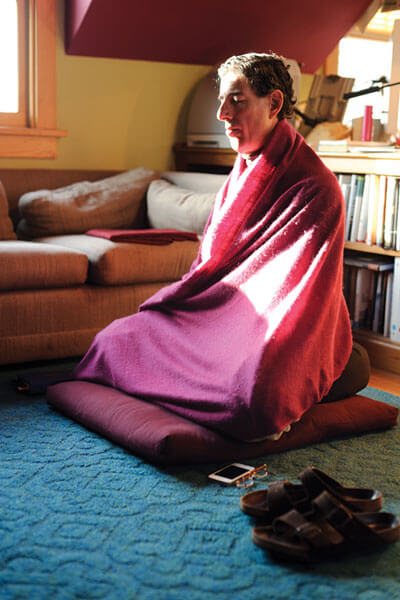

Making time for daily meditation, Richard Davidson says the practice helps to balance his own “ridiculously busy” life, which, as it happens, includes researching and writing about meditation. Photo: Jeff Miller

A leading UW researcher says everyone has an emotional style — and you can train yourself to change.

Early on, Richard Davidson’s interests in emotion and meditation were not considered an auspicious start to a productive research career.

Undaunted, he has since pioneered the field of affective neuroscience, the study of the brain’s basis for emotion, and, aided by a close relationship with the Dalai Lama, has conducted groundbreaking work with Buddhist monks to learn how meditation affects the brain.

Over three decades, the William James and Vilas Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry, who still meditates daily, has largely redefined how scientists think about emotion, showing that the natural malleability of the brain extends to emotion as well — and that it can be trained toward greater attention, awareness, and even happiness through mental practice.

In a new book written with health and science reporter Sharon Begley, The Emotional Life of Your Brain, Davidson describes six distinct emotional dimensions — resilience, outlook, social intuition, self-awareness, sensitivity to context, and attention — and says that each has a defined and measurable neural signature. How these six come together create what he calls your emotional style: your personality and how you live and respond to experiences.

With the support of private gifts and research grants, Davidson founded the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at UW–Madison’s Waisman Center in 2008 to study and harness the power of positive emotions. He recently talked to On Wisconsin about life, work, and, yes, the pursuit of happiness.

How did you arrive at these six dimensions of emotional style?

Completely post hoc, based on thirty years of my scientific work. They are a way to capture some of the key dimensions of individual differences that I think are important in accounting for a person’s emotional style. Each is based upon a specific program of empirical research that involves looking at the neural [signals] of these individual differences.

Very early on in my career, one thing that struck me is that the most important thing about human emotion, by far, is variability: in response to the same challenge, different people respond in different ways. And I was convinced that this had something very important to say about why certain people are more vulnerable to life’s slings and arrows and why other people are more resilient. That is still the most important question that drives the majority of our research. These styles all help to inform us about why some people are more vulnerable and some people are less vulnerable to different kinds of emotional challenges.

When you started, emotion was regarded as something that could not or should not be studied scientifically. Why did you think otherwise?

I was convinced that emotion was a very important feature of behavior. It is very much involved with motivation, with critical aspects of decision-making, and it was clear to me — as someone interested in what happens when things go awry — that it is involved in disorder. Early in graduate school, I discovered [Charles] Darwin’s book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, and it was absolutely thrilling. Specific emotions evolved to solve specific problems that were posed in our evolutionary past, and they are in our repertoire for a reason.

I don’t think there’s a single part of the brain that’s unaffected by emotion, nor a part of the brain historically assigned to emotion, that doesn’t also play a role in cognition. These are intimately interwoven.

One interesting side note: in the Tibetan language, there’s no word for emotion. Emotion is [considered] part of everything, so it doesn’t have its own unique word. Early on in our dialogues with the Dalai Lama, this was a big obstacle for the translators.

Can we actually train the emotional side of our brain?

Even today, we’re largely taught that personality traits and emotional disposition congeal around adolescence and are basically fixed for the rest of your life, unless a major trauma occurs. That never satisfied me. … My essential point is that you can engage in systematic mental practices to change aspects of emotional style. We normally don’t think about happiness as a skill, but to me, there’s no reason to think about it any differently than playing the piano or playing chess.

How have your own experiences with meditation influenced your approach to these questions?

There’s no question that my personal involvement in meditation has played an enormously important role. It has given me an appreciation for the importance of some of the positive qualities nurtured by meditation and the notion of plasticity — that our brains change in response to experience and training. To an external observer, I lead a very stressful life. I’m ridiculously busy; I’m overcommitted. But I love coming to work every day, and I get a lot of nourishment from my interactions with those around me. I feel that my own meditation practice has helped me generate a lot of positive energy to keep doing this in a very balanced way, despite what objectively may look very stressful.

Has your emotional style changed over time?

Yes, definitely. I used to be much more volatile, no question, and there was a period in my scientific career when I used to just fly off the handle. I cannot remember the last time that happened. It’s not to say that I don’t get irritated — I do — but it’s much more modulated.

Your book describes ways that people can work to shift where they are on the scale of each dimension of emotional style. Is there an optimal style?

One end of each continuum is not necessarily better than the other end. A lot depends on what environment you’re in, what you choose as your occupation, whom you choose as your partner. I honestly don’t believe there is a “best” way, and one of my hopes in writing this book is to cultivate an appreciation for diversity. Our society couldn’t function without a diversity of emotional styles.

Where do you see this work going?

It’s my hope that we can start using this in research … that some of the interventions we describe for transforming emotional style can be put into practice in major societal venues. The two biggest ones are health care and K–12 education, to promote healthy emotional styles and help kids develop on a more positive trajectory. These are all things we’re actively exploring now at the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds.

This interview was conducted and edited by Jill Sakai PhD’06, a science writer for University Communications.

Published in the Summer 2012 issue

Comments

jillmarie June 15, 2012

Hi I have found this article very interesting. I am very emotional and sensitive and believe this is because of my childhood. Yes I was walking on egg shells most of the time and yes it has taken me about 45 years to realise who I am as I have had to be a chameleon to fit in all my life. What people have expected of me I have acted out. I was a child with no voice and with no sense of self and felt invisable. I have been a kindergarden teacher for the past 15 years and think this is so because I am trying to heal my inner child or the child that was abandoned. its been really hard and I wish I was normal and could just let go rather than hanging on to this fight or flight mode.x

edward June 16, 2012

Jillmarie,

I think I know where you are coming from. Having been diagnosed with bipolar in my early tWenties, I have spent much of my life in “fight or flight”. I have tried many drugs, but the things that helped me heal the most are working with youth, therapy, and meditation. If you can find a meditation class, I think that is the easiest way to get started.

Edward

sebastian September 3, 2012

Jillmarie,

Two points to ponder: (i) there is no such thing as ‘normal’; (ii) even if there were, it would be a mistake to assume its desirability.

Charlotte Rubinstein March 5, 2013

The article is well written and informative. Meditation is a great place to find a different way of feeling and acting.

Beth March 14, 2013

I find I have so much in common with jillmarie’s experiences from childhood. In fact at one point in my life I was a very successful salesperson utilizing the chameleon qualities of people pleasing to manipulate my customers. Yet, I too had no sense of who I was when I wasn’t trying to please someone else. I also found that others took advantage of my disproportionate need to please and impress them. I have felt both alone and unknown. I am now looking for a way out of anger towards my children who had actually grown up healthy and stronger than I did. I am angry, I believe, because I feel jilted that they don’t go out of their way to please me nor do they feel guilty when I put the pressure on them to do so. While I should be proud of their emotional health I need help to let go of feeling jipped. I pleased my parents and, gosh, so my kids should “please” me. Maybe meditation is the medication that can help me grow calm and serene rather than mean.

Beth March 14, 2013

I find I have so much in common with jillmarie’s experiences from childhood. In fact at one point in my life I was a very successful salesperson utilizing the chameleon qualities of people pleasing to manipulate my customers. Yet, I too had no sense of who I was when I wasn’t trying to please someone else. I also found that others took advantage of my disproportionate need to please and impress them. I am now looking for a way out of anger towards my children who had actually grown up healthy and stronger than I did. I am angry, I believe, because I feel jilted that they don’t go out of their way to please me nor do they feel guilty when I put the pressure on them to do so. While I should be proud of their emotional health I need help to let go of feeling jipped. I pleased my parents and, gosh, so my kids should “please” me. Maybe meditation is the medication that can help me grow calm and serene rather than mean.