The Kick that Captivated a Country

With one historic play, Badger football legend Pat O’Dea put Midwestern college teams on a footing with their Ivy League peers.

Pat O’Dea, who played football at Wisconsin between 1896 and 1899, was the most celebrated gridiron hero the university had ever known. In his book The Opening Kickoff, Dave Revsine, the lead studio host at the Big Ten Network, has used the story of O’Dea to take a look at the early history of college football. The life of O’Dea, who was called the “Kangaroo Kicker,” took some secretive turns after college that involved an indictment for embezzlement, an undercover job, and a new identity, and Revsine spent many hours in the UW–Madison Archives, poring over old issues of the Daily Cardinal and other sources to set the record straight. The Opening Kickoff, which is excerpted here, was released in July by Lyons Press.

The bespectacled man stared out at the adoring throng — five thousand fans braving the chilly Midwestern November night, all there to see him. An enormous bonfire raged in front of him, its flames leaping four stories into the air. All around him, people craned their necks just to catch a glimpse of his creased face, of his graying hair, of his fedora hat. He was, after all, a legend. For decades, young boys growing up in Wisconsin had known the name of this Australian immigrant before they knew the president’s. Yet, they had never expected to get this chance — the chance to lay eyes on the greatest hero their state had ever known. There was a simple reason for that. They had thought he was dead.

But Pat O’Dea was very much alive. He was sixty-two years old, carrying the same 170 pounds on his six-foot-one-and-one-half-inch frame that he had thirty-five years earlier, in the late 1890s, when crowds like this one had last cheered him — a football player described as “the closest thing to a Paul Bunyan that the game has produced.”

That had all been so long ago, though, before he’d made a mess of his life. Before the disintegrated marriage. Before his failure first as a coach and then as a businessman. Before the indictment. Before he ran away from it all, changing his name and slinking off in shame. Somewhere he had a daughter whom he had never met. Did she know of his fame? Perhaps she was out there now, among the adoring masses.

The last time O’Dea had set foot in this town, in his beloved Madison, he had taken the cheers for granted — seen them as a birthright. But it had been ages since he’d been in the spotlight. And now, the player who Walter Camp, the father of the modern game, once said “put the foot in football as no man ever has or as no man probably ever will again,” was back in front of the reverent masses.

O’Dea’s eyes began to moisten as the memories flooded back to him.

And then he spoke. His words were not profound. He had told himself he wouldn’t reveal much. The fans knew his legend. But they did not know his secrets. Besides, when it came to O’Dea’s life, it was hard to separate the myth from the reality. His silence on the most important matters simply added more mystique to an already fantastic story.

“They told me the Wisconsin spirit had changed,” he said into the microphone from his perch on the balcony outside the old library building. “But I want to tell you that you have the same Wisconsin spirit we knew and loved years ago.”

And then, as he had so many times before, O’Dea heard the cheers.

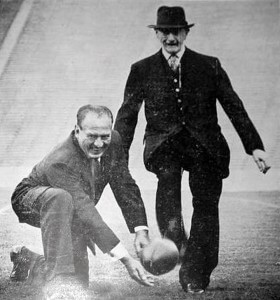

Pat O’Dea, right, prepares to kick a football held by fellow gridiron great Red Grange at Camp Randall stadium before the 1957 Homecoming game against Illinois. Courtesy of Dave Vitale.

Wisconsin’s Pat O’Dea stood alone, twelve yards behind his center, Roy Chamberlain, and sixty yards away from the goal post. It was a seemingly ordinary moment very early in a seemingly ordinary football game — Thanksgiving Day, 1898. O’Dea’s Badgers were at Sheppard Field in Evanston, Illinois, taking on Northwestern.

The Wisconsin captain called out the signals. “Nine, ten,” the Australian yelled. “Nine, ten.” His teammates looked at him incredulously. Unbeknownst to the Northwestern players and the three thousand or so fans looking on, Pat O’Dea was attempting to make history.

A speech from coach Phil King, less than an hour earlier, had brought O’Dea to this moment. King was in his third year leading the Badgers. His initial seasons had been remarkable successes, as Wisconsin had captured the first two championships of the newly formed Western Conference, the precursor of the modern-day Big Ten.

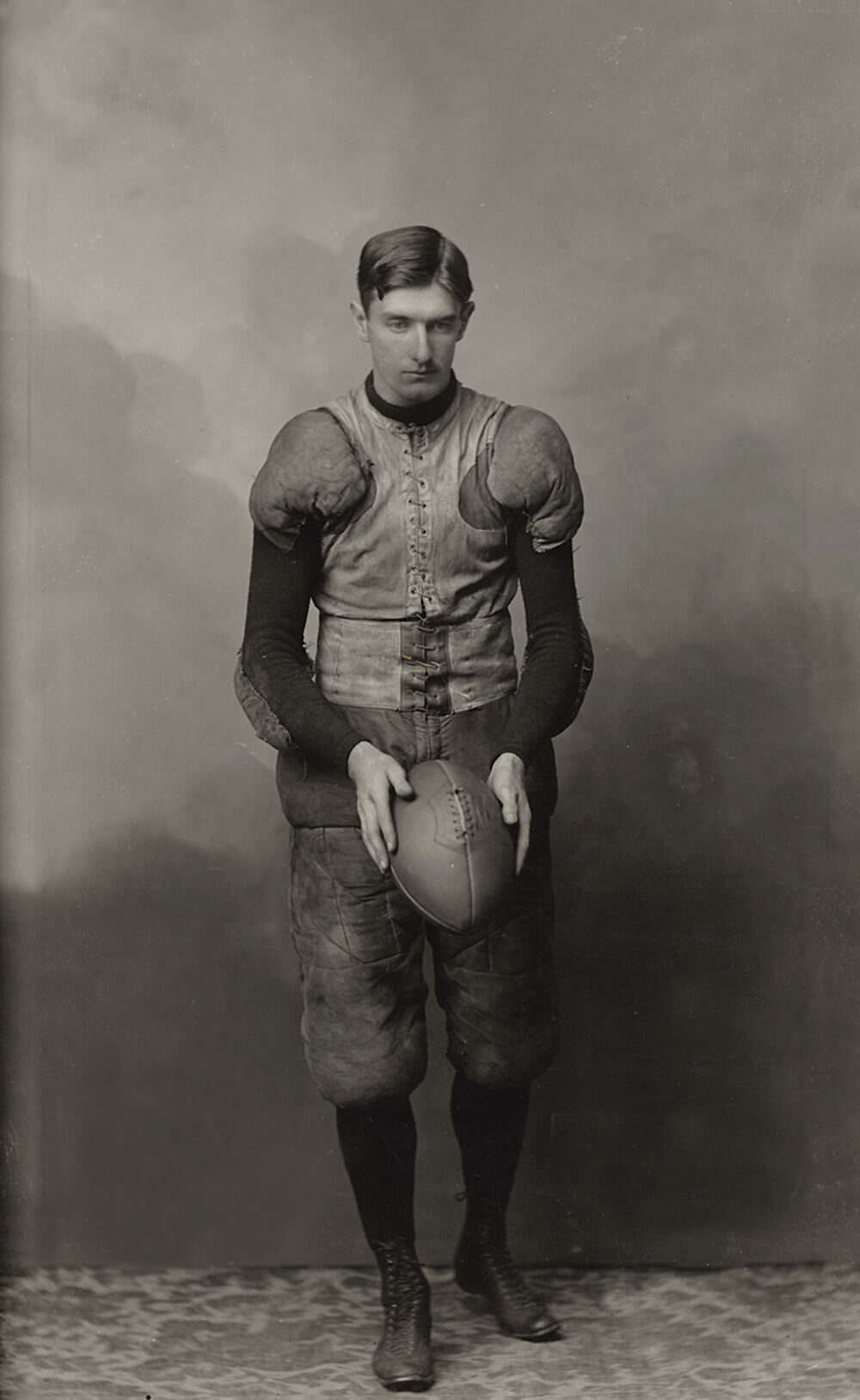

In O’Dea, Wisconsin boasted one of the Midwest’s first true superstars. The lanky twenty-six-year-old didn’t necessarily look the part of a rugged football player. He was strikingly handsome. His pleasant and expressive face was topped by a generous helping of seemingly never-ruffled light brown hair. It was O’Dea’s legs that really stood out, though, described by one contemporary as “abnormally long and wonderfully developed.”

Those legs were his weapon of choice. In a short period of time, they had earned him remarkable fame. He drew headlines everywhere he went — the most celebrated kicker in the country at a time when, due to the nature of the rules, the kicker could literally take over the game. With O’Dea booting and the Badgers winning, Wisconsin games were always a big deal. Always, that is, until this one.

The Badgers were coming off a devastating defeat, having fallen 6–0 twelve days before to the University of Chicago Maroons, their most bitter rival. As a result, the Maroons had stolen the headlines during the course of the week as Thanksgiving Day had drawn nearer. They were scheduled to host Michigan at Marshall Field on their Hyde Park campus at exactly the same time the Badgers and Purple were squaring off in Evanston. Since neither team had lost to another Western Conference foe all season, the Michigan-Chicago game was now the battle for the championship. The contest between the Badgers and a middling Northwestern team was, in many ways, meaningless.

In his book, Dave Revsine makes the case that college football dealt with the same issues in Pat O’Dea’s era as it does now, differing mainly in scope.

As he had stood before the team in the cramped dressing room wedged under the grandstand at Sheppard Field, King couldn’t help but notice the ambivalence. Sensing his players needed some inspiration, King delivered a short, unconventional speech. “Gentlemen,” he told them, “score in the first two minutes, and tonight, we’ll celebrate with all the champagne you can drink.”

The cheer that went up from the players was quickly replaced by mild panic. Two minutes? As powerful as the Badgers were, two minutes wasn’t a whole lot of time — particularly in an era when the forward pass was still illegal and results like that 6–0 final against Chicago were commonplace. Still, the team charged onto the field with a newfound sense of purpose.

O’Dea went through his warm-ups, which in and of themselves were worth the price of admission. He boomed jaw-dropping punts and converted remarkable dropkicks, routinely splitting the uprights from distances others could only dream of. In a time when field goals were worth five points — one more than touchdowns — and teams often punted on first down, kicker was the single most glamorous position on the field, and the handsome, exotic, and talented O’Dea was redefining the position. He was the best kicker in the West, and fans in that part of the country believed he was superior to any player in football.

Of course, they couldn’t say for sure. Games between Eastern and Western teams were virtually unheard of, so most of them had never seen the players from traditional powerhouses such as Yale, Harvard, and Princeton — the schools that had invented the game about thirty years earlier. Those colleges were the gold standard. The West was an afterthought.

A total of 187 players had been named “All-Americans” since the first selections were made back in 1889. All 187 had been from the East.

Wisconsin won the coin toss, so the Purple kicked off to O’Dea, who caught the ball at his own 10-yard line and ran it back to the 20. Then, in an effort to improve their field position, O’Dea and the Badgers chose to punt the ball right back to Northwestern, hoping to pin their opponents deep in their own territory.

O’Dea’s kicking style was an unusual one. When he made contact with the ball, he did so with both feet off of the ground — appearing almost to jump at the pigskin. He did this on both punts and dropkicks, a now-obsolete form of kicking in which a player would bounce the ball off the grass and kick it on its way back up. Though placekicks played a minor role in the game, dropkicks were the typical way to convert a goal.

O’Dea unleashed a phenomenal punt, one that spun high in the air before landing 50 yards down the 110-yard field, at Northwestern’s 35-yard line. The home team kicked it right back, but the punt was a poor one, giving the Badgers the ball near midfield. In light of the improved field position, Wisconsin chose to hang on to the ball and try to move it toward the Purple goal, hoping to gain the requisite five yards in three downs.

The Badgers tried two halfback runs, neither of which netted any yardage. The game was nearly two minutes old. O’Dea dropped a dozen yards behind the line and barked out the shocking “nine, ten” signal.

“Slam” Anderson didn’t believe what he had heard. As one of the two ends for the Badgers, his duties changed significantly depending on O’Dea’s signal call. On a punt, Anderson’s job was to race down the field as fast as he could in an effort to tackle the opponent’s return man. On a dropkick, Anderson would stay in, blocking the opponent’s rusher in order to give O’Dea time to get his boot off. Yes, he knew that O’Dea had called out a signal for a dropkick — but he also knew that it was a preposterous notion. The Aussie was sixty yards from the goal. No one in the history of the game had ever converted a dropkick from farther than fifty-five yards out.

Convinced that O’Dea had simply misspoken, Anderson sprinted down the gridiron at the snap. That decision nearly doomed the play to failure. When the Aussie caught the ball, he almost immediately had a Northwestern rusher in his face, in prime position to block the kick. It was the man Anderson had neglected to block. O’Dea avoided him with a quick sidestep move, let the ball bounce, and simultaneous with it hitting the ground made perfect contact with his right foot, resulting in a mighty dropkick.

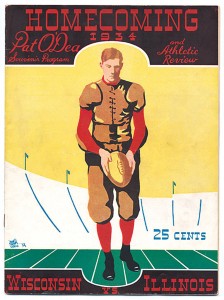

The 1934 Homecoming program commemorated O’Dea’s appearance at the celebration — his first visit back to campus in 35 years.

The ball flew more than half the length of the field on an awe-inspiring arc, seemingly on a collision course with the grandstand behind the north goalpost. It sailed squarely between the posts and over a fence that lined the field, landing easily ten yards beyond the goal line, just in front of the stands. O’Dea had booted it at least 210 feet. In a game where lengthy kicks were celebrated the way long runs or passes are today, this was the single most remarkable football play anyone in attendance had ever witnessed.

The initial reaction was one of stunned silence. That bewilderment soon turned to an orgy of sound. Wisconsin fans hugged one another and threw their hats into the air. The game umpire, Everts Wrenn, himself somewhat astonished, signaled a goal. The only person in Evanston who didn’t seem fazed by the achievement was O’Dea himself, who, perhaps eager to get on with the now-assured champagne feast, called on his team to assemble at midfield for the ensuing kickoff.

The early 5–0 lead quickly ballooned as the Badgers went on to win 47–0. O’Dea’s record-breaking kick was the story. The Milwaukee Sentinel led its entire paper with a bold front-page headline in the left-most column blaring: O’DEA KICKS A 60-YARD GOAL. Just to the right was the story deemed the second most important of the day, announcing that the Spanish cabinet had authorized the signing of the peace treaty that would end the Spanish-American War.

The Chicago Tribune described O’Dea’s performance as “miraculous,” continuing: “Everyone figured O’Dea would work havoc with the chances of the home team, but that he would do such phenomenal punting and dropkicking as that which electrified the crowd was beyond the wildest dreams of his most ardent supporters.” The Duluth News Tribune put it more succinctly, saying simply, “Pat O’Dea is king.” Though there was certainly plenty of newspaper ink spilled regarding Michigan’s 12–11 win over Stagg’s Maroons, O’Dea’s kick made headlines nationwide and gained the attention of the Eastern establishment. At the end of the 1898 season, the Aussie was one of the first Westerners ever named to the All-American team. The legend of “The Kangaroo Kicker” was born.

From the book The Opening Kickoff by Dave Revsine. Copyright © 2014 by Dave Revsine Used by permission of Globe Pequot Press, www.globepequot.com.

Published in the Fall 2014 issue

Comments

No comments posted yet.