World Peace

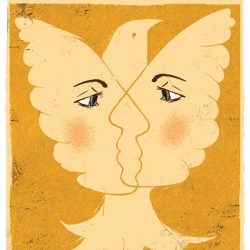

Edel Rodriguez

World Peace

Donna Hicks has found that the simple concept of honoring human dignity has the power to achieve reconciliation when nothing else can.

On a steamy tropical morning in a Latin American country in 2003, Donna Hicks PhD’91 entered a room packed with government and military leaders in crisis. She was there to lead the participants, entrenched in intractable conflict, in a communications workshop. The president of the country hadn’t planned to stay until Hicks, acting on instinct, suddenly asked his permission to shift the focus to another topic altogether, one she’d been theorizing about for years: dignity. The president canceled his meetings and pulled up a chair.

Afterward, one high-ranking general told Hicks she not only helped the people in the room, but she also saved his marriage. As Hicks recalls, that was the day the dignity model was born — a tool for conflict resolution that she would eventually outline in a book titled Dignity, which was published in 2011 by Yale University Press.

Since then, Hicks, who spent fifteen years in Madison and earned her PhD under UW Professor Robert Enright before taking a job with Harvard’s Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, has applied the model successfully everywhere from Northern Ireland to corporate board rooms, always eliciting the same, awed reaction. “It’s not just a political issue that I uncovered,” says Hicks. “This is an issue that every single human being, no matter where I am in the world, says, ‘That’s it!’ ”

The premise is deceptively simple: the human brain experiences dignity violations in the same way it interprets a physical threat. With an awareness of how we violate the dignity of others and how our own dignity is violated, we can resolve even the most lengthy, brutal, seemingly hopeless conflict. Sound hyperbolic? Not according to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the South African human-rights activist, who wrote the foreword to Hicks’s book — and called her a prophet.

“Far more significant than any advice given is the driving awareness that permeates this book,” writes Tutu, “that in the concept of human dignity we have in our hands, as it were, the key to the conundrum of the ages: How can peace on earth be found?”

In an interview with On Wisconsin, Hicks talks about the dignity model — where it came from, why it works, and what it’s like to now count Tutu as a friend.

Naming It

Dignity is one of those words most of us have a gut feeling about, but when asked to define it, we can’t quite pin it down — a concept Hicks explores in her book. She draws a distinction between similar words such as respect or, conversely, humiliation. “Dignity is an internal state of peace that comes with the recognition and acceptance of the value and vulnerability of all living things,” writes Hicks.

While it’s not a new concept, Hicks’s model seems to have slid neatly into an unexpectedly large void. “At the time I was writing this book, there was nothing else written on dignity,” she says. One of the biggest challenges was “unlearning how to write like an academic,” which she combatted with narrative nonfiction courses over the seven years she spent writing. Drawing from psychology, neuroscience, evolutionary biology, and decades of observation and experience in the international conflict field, Hicks has identified ten essential elements of dignity — and the model has catapulted her conflict-resolution work into a whole new stratosphere. [See sidebar.]

“I feel like I’ve opened up a door that had been previously closed, yet every single one of us knows what I’m talking about,” she says. “The major contribution that I feel I made around this work is to name something — to name something that each and every one of us knows deep in our soul, but we rarely talk about it.”

Fight or Flight

Citing research by neuroscientists, Hicks asserts that the human brain experiences dignity violations in the same way it interprets a threat from a knife-wielding attacker, triggering the fight-or-flight response that prompts us to react with overpowering emotion. This explains the shaking, the sweating, the rapid breathing, and the other symptoms triggered by emotional abuse or a heated argument with a loved one. When our dignity is violated, we are physically incapable of moving forward, unless that violation is acknowledged.

“The evolutionary part, that is probably the biggest bonanza,” says Hicks. “When I was doing my research, I came across evolutionary psychology and evolutionary biology. So much is being written about it now, but it’s not in the schools. I teach a class at Columbia every semester, and half of the students aren’t even aware of what it is I’m writing about. That’s why we’re so sensitive and we so easily hurt one another: because we have a twenty-first-century human experience with hardware that was meant for our early ancestors one hundred thousand years ago.”

Not Just for Women

In the male-dominated world of global leaders and warring parties, the dignity model could be dismissed as … well, feminine.

However, says Hicks, “The thing that I never expected was how much men are gravitating to this. I think women might have a better grasp of it, you know, a more intuitive grasp of it. But the men feel it, I’m telling you.”

As a psychologist, Hicks had always been sensitive to the emotional undercurrents raging through every negotiation she’d ever facilitated; she also knew it didn’t work to walk into a room of tense, embattled higher-ups — especially men — and ask them to talk about their feelings.

“One day, I remember thinking, ‘If we could only get people talking about those emotional experiences that they’re stuck in,’ ” says Hicks. “I could see that these were really brilliant people, and yet, when they sat down at a negotiating table, it was as if that part of them just vanished.”

But when Hicks began to reframe the discussion from feelings to dignity, the wall of silence instantly crumbled.

“If I said, ‘Tell me a time when you felt your dignity was violated’. … Everybody had a story,” says Hicks. “Everybody had a million stories. So there was something legitimizing about using that word. … They didn’t feel the shame of admitting that they were emotionally incapable of solving this problem.”

Encouragement from Tutu

Back in 2005, Hicks was recruited by the BBC for a three-part television documentary, Facing the Truth, which brought together Catholic and Protestant victims and perpetrators of conflict in Northern Ireland for face-to-face encounters. It was an opportunity to flex the muscles of the dignity model on a televised stage. Filming took place at an estate outside Belfast, and Archbishop Tutu chaired a small team of project facilitators. The two quickly developed what Hicks today calls “such a deep bond.”

“He is a moral authority for the whole world,” says Hicks. “In terms of dignity, he just seems to embody it for me.”

Hicks and Tutu have continued to work together during the years since. The two email and call, they’ve been guests in each other’s homes, and he helped her with the book before writing the foreword. “When the book was finished, he said, ‘Look, this is your baby, and you have put this out into the world,’ ” says Hicks, who does not have children. “ ‘You gave birth to a beautiful thing, and I want you to feel proud of it.’ ”

In 2012, news photographers captured a pivotal moment when Queen Elizabeth II of England shook hands with Northern Ireland’s deputy first minister, Martin McGuinness, a former IRA commander. “We — including the BBC producers — like to think that Facing the Truth might have played a little role in paving the way for this handshake to happen,” says Hicks.

Afterward, a spokesman for Sinn Fein, the political branch of the IRA, released the following statement: “[McGuinness] emphasized the need to acknowledge the pain of all victims of the conflict and their families.” Perhaps without realizing it, McGuinness was affirming that one of the ten essential elements of the dignity model — acknowledgment — was in play during the public reconciliation.

Dignity and Forgiveness

It’s only with hindsight that Hicks can see how brilliantly her dignity model harmonizes with the forgiveness work of Robert Enright. “I was interested in international conflict, but I was also interested in how people create meaning around conflict,” says Hicks, who worked closely with Enright in the late eighties before earning her PhD. “I was drawn to his exploration of the deeper philosophical meaning behind conflict. Looking back on it, he was such a mentor, because he really understood this stuff in a way I didn’t.”

Twenty years and a lifetime of experience would pass between the time when Hicks worked with Enright and the year she published Dignity, but the intersections between their work then and now are undeniable. Hicks says both dignity work and forgiveness work focus on the desire to understand the context of the perpetrator, the larger life experience that led a person to act out. She says they’re both “paths to reconciliation” — tools to help people put the past to rest rather than seek revenge.

“They’re first cousins, dignity and forgiveness,” says Hicks. “In fact, I feel like one of the greatest dignified acts one can do is to forgive.”

As for her early mentor, “[Enright] had such integrity,” she says. “Looking back, what I am just so grateful to him for is that now I have the words to describe it: he had such dignity.”

A Dignity State?

Hicks is now in high demand as a speaker and facilitator, addressing and working with people across the globe — not only in the political context, but also within corporations, schools, churches, nonprofits, and other organizations. She’s developing a training manual so that other dignity advocates can continue her work. And she has written a short document, “The Declaration of Dignity” (declaredignity.com), that essentially asks everyone to pledge to live consciously in a way that honors the dignity of all people to end suffering in the world. She would also like to develop a dignity-based curriculum for school systems.

“I’m a bit overwhelmed, to tell you the truth,” Hicks says. “I never imagined it would have such an impact. This book basically has a life of its own now.”

On Christmas Eve 2011, John Mitchell, an Episcopalian priest in Manchester, Vermont, gave a sermon on the dignity model, then invited Hicks to visit and address the town. He invited everyone, including the local rabbi and the headmasters of the area schools. He signed the pledge and is attempting to get everyone else to sign it, too.

“He’s decided that he wants to create a dignity community,” says Hicks, grinning. “Who knows, Vermont may become the first Dignity State. Isn’t that fabulous?”

Maggie Ginsberg-Schutz is a Madison-based freelance writer.

Published in the Spring 2013 issue

Comments

Milly Doe April 15, 2013

I think this idea of dignity and sorting through people’s feelings and emotions is a most powerful concept. It is one of the greatest concepts of our existence. However, I will take it one step further. I believe animals and other creatures also deserve dignity. When we slaughter animals and torture, rape, molest and abuse them and then sell them to eat, how horrifying is that? I am not a vegetarian. I think we need to treat all beings with dignity. We need to shift our perspective and we need to acknowledge when we mutilate and abuse any creature with disdain and brutality, how can we live with ourselves? This can also be applied to our earth too. I believe this concept/article/book provides a critical turning point in our existence. We need to create social groups, church groups, community groups to discuss dignity, and to widen the scope of the concept to include all living things. This is the right step to turn around our eve of destruction.

jane ayer April 30, 2013

To Milly Doe and others: have you ever implemented principles of Buddhist practice. See especially references to pledges to do no harm to all sentient beings.